I’m getting worn down by clinicians – often other specialists – who insist that CT imaging of the brain is mandatory prior to lumbar puncture in all patients. There is surely a subgroup of patients (especially young ones) in whom the benefit:harm balance of CT comes out in favour of NOT doing the imaging. In these cases, getting the scan is not ‘defensive medicine’ but ‘offensive medicine’ – offending the principle of primum non nocere. During ED shifts I have recently had to perform online searches in order to furnish colleagues and patients’ medically qualified relatives with printouts of the literature on this. This page is here to save me having to repeat those searches. Regarding the practice of performing a routine head CT prior to lumbar puncture to rule out risk of herniation:

- Mass effect on CT does not predict herniation

- Lack of mass effect on CT does not rule out raised ICP or herniation

- Herniation has occurred in patients who did not undergoing lumbar puncture because of CT findings

- Clinical predictors of raised ICP are more reliable than CT findings

- CT may delay diagnosis and treatment of meningitis

- Even in patients in whom LP may be considered contraindicated (cerebral abscess, mass effect on CT), complications from LP were rare in several studies

Best practice, it would seem, is the following

- If you think CT will show a cause for the headache, do a CT

- If a CT is indicated for other reasons (depressed conscious level, focal neurology), do a CT

- If a GCS 15 patient is to undergo LP for suspected (or to rule out) meningitis, and they have a normal neurological exam (including fundi), and are not elderly or immunosuppressed, there is no need to do a CT first.

- If you’re seriously worried about meningitis and are intent on getting a CT prior to LP, don’t let the imaging delay antimicrobial therapy.

Here are some useful references:

1. The CT doesn’t help

CT head before lumbar puncture in suspected meningitis BestBET evidence summary: In cases of suspected meningitis it is very unlikely that patients without clinical risk factors (immunocompromise/ history of CNS disease/seizures) or positive neurological findings will have a contraindication to lumbar puncture on their CT scan If CT scan is deemed to be necessary, administration of antibiotics should not be delayed. BestBETS website

Computed Tomography of the Head before Lumbar Puncture in Adults with Suspected Meningitis Much cited NEJM paper from 2001 which concludes: “In adults with suspected meningitis, clinical features can be used to identify those who are unlikely to have abnormal findings on CT of the head” N Engl J Med. 2001 Dec 13;345(24):1727-33 Full Text

Cranial CT before Lumbar Puncture in Suspected Meningitis Correspondence in 2002 NEJM including study of 75 patients with pneumococcal meningitis: CT cannot rule out risk of herniation Cranial CT before Lumbar Puncture in Suspected Meningitis N Engl J Med. 2002 Apr 18;346(16):1248-51 Full Text

2. The CT may harm

Cancer risk from CT Paucis verbis card, from the wonderful Academic Life in EM

3. Guidelines say CT is not always needed

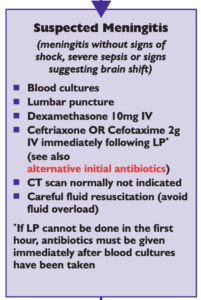

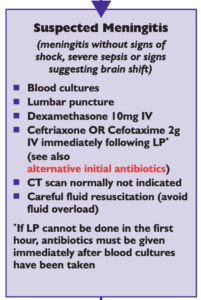

National (UK) guidelines on meningitis (community acquired meningitis in the immunocompetent host) available from meningitis.org. , including this box:

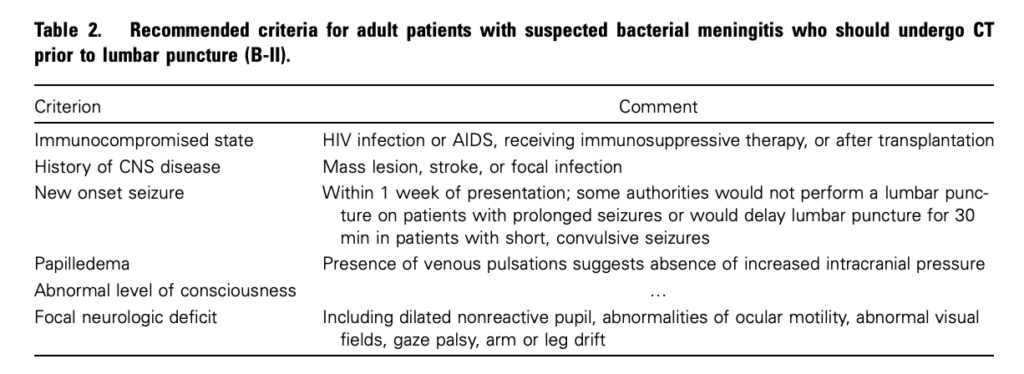

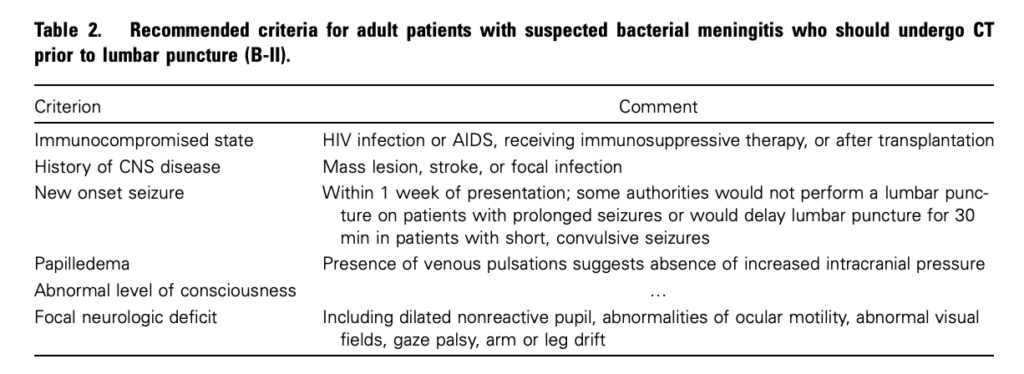

Practice Guidelines for the Management of Bacterial Meningitis These 2004 guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America provide the following table listing the recommended criteria for adult patients with suspected bacterial meningitis who should undergo CT prior to lumbar puncture:

Clin Infect Dis. (2004) 39 (9): 1267-1284 Full text

4. This is potentially even more of an issue with paediatric patients

Fatal Lumbar Puncture: Fact Versus Fiction—An Approach to a Clinical Dilemma

An excellent summary of the above mentioned issues presented in a paediatric context, including the following:

On initial consideration a cranial CT would seem to be an appropriate and potentially useful diagnostic study for confirming the diagnosis of cerebral herniataion. The fallacy in this assessment has been emphasized by the finding that no clinically significant CT abnormalities are found that are not suspected on clinical assessments. Further, as previously noted, a normal CT examination may be found at about the time of a fatal herniation. Thus, the practical usefulness of a cranial CT in the majority of pediatric patients is limited to those rare patients whose increased ICP is secondary to mass lesions, not in the initial approach to acute meningitis.

Pediatrics. 2003 Sep;112(3 Pt 1):e174-6 Full Text

The last words should go to Dr Brad Spellberg, who in response to the IDSA’s guidelines wrote an excellent letter summarising much of the evidence at the time, confessed:

Why do we persist in using the CT scan for this purpose, despite the lack of supportive data? I am as guilty of this practice as anyone else, and the reason is simple: I am a chicken.

Clin Infect Dis. (2005) 40 (7): 1061 Full Text