In the resus room, clarity of communication between team members is critical to patient safety and effective resuscitation. We are used to following standardised clinical algorithms for cardiac arrests and many other emergency presentations, but there is no standardisation of vocabulary or communication style. Communication failures are a major source of error in resuscitation, suggesting this is an area in which we need to improve.

Defining your lexicon

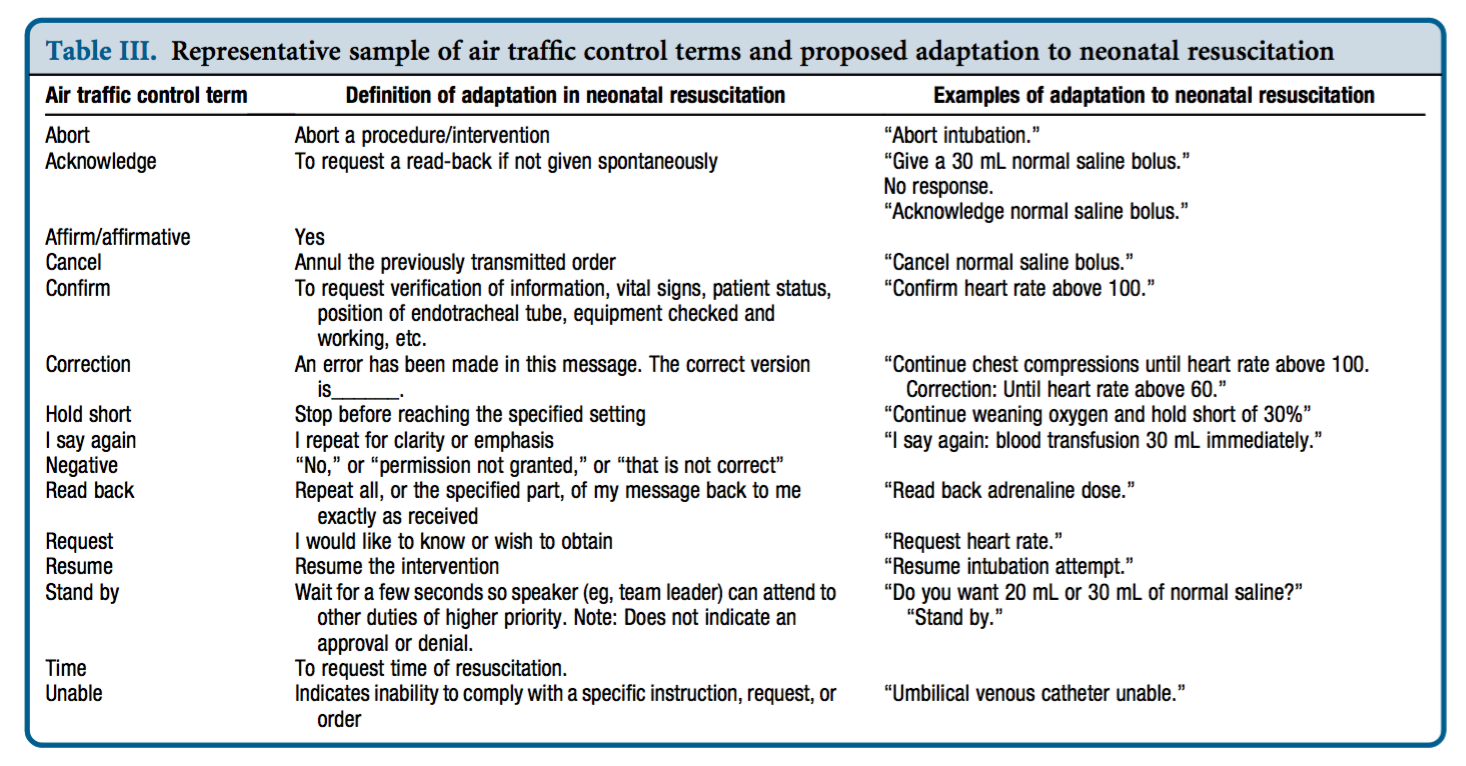

A contrast with the aviation industry was drawn by neonatologist Dr Nicole Yamada, who points out that pilots and air traffic controllers use an effective, concise, standardised set of words and phrases that are universally understood, for example ‘stand by’, ‘unable’, ‘read back’, and ‘cancel'(1). She proposed adapting a similar resuscitation-specific lexicon modelled after aviation communication which ‘would aid in streamlining communication during time-pressured clinical situations when seconds count and errors can kill.‘(2)

Dr Yamada tested this approach in a small study of simulated neonatal resuscitation. Standardised communication techniques were associated with a trend toward decreased error rate and faster initiation of critical interventions.(3)

Avoiding the fluff

In the absence of standardised approaches to communication, humans in the resus room often choose language which indirectly acknowledges social hierarchies. For ad hoc teams, phrases may be chosen which are least likely to offend people with whom we’re unfamiliar, or may be deferential in cases of real or presumed authority and expertise gradients. The consequence of this is the use of ‘mitigating language‘. Examples might be:

“Any chance you could pop a line in?”

“Would someone mind letting me know if they can feel a pulse?”

“Do you want to have a think about setting up for intubation?”

“How about we get some bag-mask ventilation happening at some point?”

“If you could have a look at his abdomen that would be awesome”

These commands (imperatives) phrased obliquely as questions or suggestions are know as ‘whimperatives‘ and are found throughout resus room dialogue, when the team leader does not wish to convey the assumption of a power relationship over her colleagues. These whimperatives are an example of ‘mitigating speech’, which refers to language that ‘de-emphasises’ or ‘sugarcoats’ the command.

In the words of Peter Brindley:

‘The danger of mitigating language illustrates why, during medical crises, we should replace comments such as “perhaps, we need a surgeon” or “we should think about intubating” with “get me a surgeon” and “intubate the patient now.”’(4)

Conclusion

There’s nothing wrong with being polite and respectful, and mitigating language may be helpful in the team building phase. However the more critical the situation, the more an authorative/directive leadership style that clearly delegates critical tasks is required(5). Standardised terminology (with closed loop communication) is likely to enhance clarity of the message and accelerate the sharing of a team mental model. Avoiding whimperatives and excessive mitigating phrases may further prevent ambiguity and imprecision, reducing the time to critical interventions.

These components of the content of resus room communication – unequivocal, standardised, and direct – should go hand in hand with the delivery of the words. Effective delivery requires optimal delivery speed and ‘command presence’. These factors will be discussed in a future post.

I’d be interested to hear what standard phrases or words you think should be in the resus-room lexicon.

1. Yamada NK, Halamek LP. Communication during resuscitation: Time for a change? Resuscitation. 2014 Dec;85(12):e191–2.

2. Yamada NK, Halamek LP. On the Need for Precise, Concise Communication during Resuscitation: A Proposed Solution. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2015 Jan;166(1):184–7.

3. Yamada NK, Fuerch JH, Halamek LP. Impact of Standardized Communication Techniques on Errors during Simulated Neonatal Resuscitation. Am J Perinatol. 2016 Mar;33(4):385–92.

4. Brindley PG, Reynolds SF. Improving verbal communication in critical care medicine. Journal of Critical Care. 2011 Apr;26(2):155–9.

5. Bristowe KK, Siassakos DD, Hambly HH, Angouri JJ, Yelland AA, Draycott TJT, et al. Teamwork for clinical emergencies: interprofessional focus group analysis and triangulation with simulation. Qual Health Res. 2012 Sep 30;22(10):1383–94.