Ready are you? What know you of ready? ~ Yoda

The Standard SALAD Approach

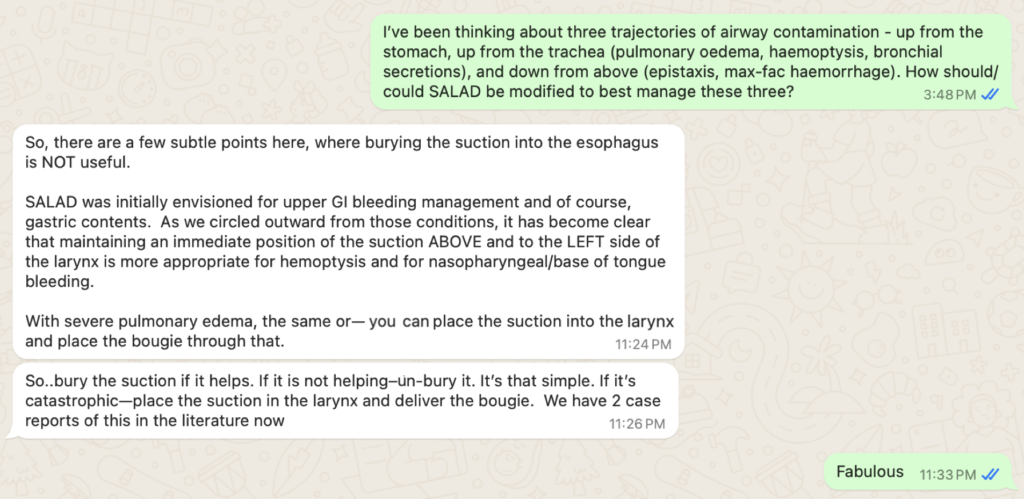

The SALAD technique (Suction Assisted Laryngoscopy and Airway Decontamination) invented by Jim DuCanto has revolutionised the way we approach contaminated airways1.

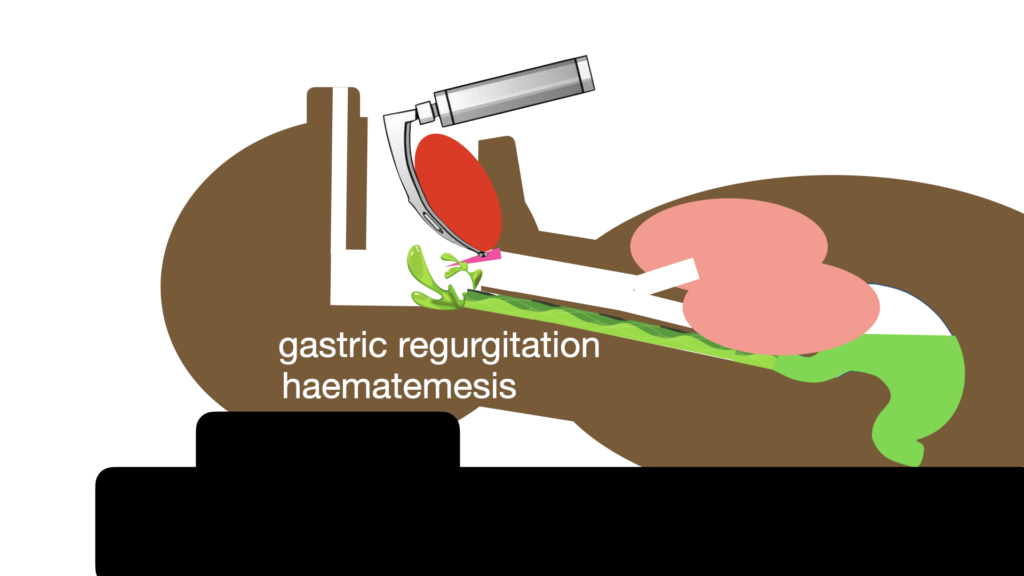

Designed to reduce the risk of aspiration and facilitate unobscured laryngoscopy, the operator leads with an appropriate suction catheter, keeping their laryngoscope blade (and video lens) ‘high and dry’. The catheter tip is then ‘parked’ in the hypopharynx/upper oesophagus.

The next move is genius – without moving the suction catheter tip, the body of the catheter is moved round so that it can be held by the operator’s laryngoscope (left) hand, between the palm and the laryngoscope. This frees up the right hand for bougie and tube insertion via a clear route to the larynx while the suction catheter continues to collect the regurgitant fluid. This works great for stomach contents and upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage.

Non-Gastric Contaminant Sources

However, not all nastiness arises from the GI tract. In my emergency medicine and prehospital critical care practice, we intubate patients with maxillofacial trauma, massive epistaxis, post-tonsillectomy bleeding, drowning, acute pulmonary oedema, and massive haemoptysis.

This led me to consider that there are three general trajectories by which contaminant fluid can reach the pharynx and impede laryngoscopy: (1) from above, ie. mouth and nose; (2) from below, via the GI tract; and (3) from below, via the respiratory tract. The SALAD technique may need to be modified or supplemented depending on the trajectory.

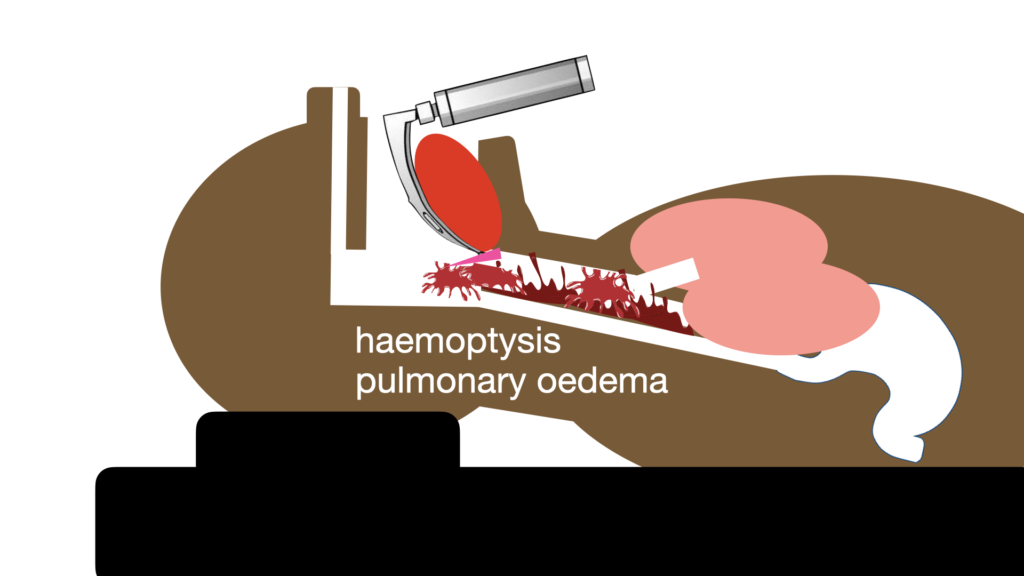

I contacted Jim last year about this to get his thoughts:

Not surprisingly he made perfect sense – park (even bury) the catheter in the oesophagus when the GI tract is the problem, otherwise position it above and to the left side of the larynx.

Note that Jim mentions pulmonary oedema and reminds us of the bougie-through-the-suction-catheter trick; more on that below.

Let’s consider the three trajectories and what our options are:

Trajectory 1 – Stuff coming UP – from the GI Tract

Think haematemesis, small bowel obstruction, alcohol and kebab intoxication, ozempic use?

Here the classic SALAD positioning of the suction catheter in the hypopharynx/proximal oesophagus makes perfect sense

Modifications or supplemental actions:

It can be prudent to insert a gastric tube and decompress the stomach prior to intubation in high risk patients if conditions allow.

During laryngoscopy, if the bad stuff just keeps on coming (think aorto-enteric fistula), consider deliberately intubating the oesophagus first with a tracheal tube and using that to divert the flow to a suction source, and use a second suction to decontaminate the airway and clear a path for laryngoscopy.

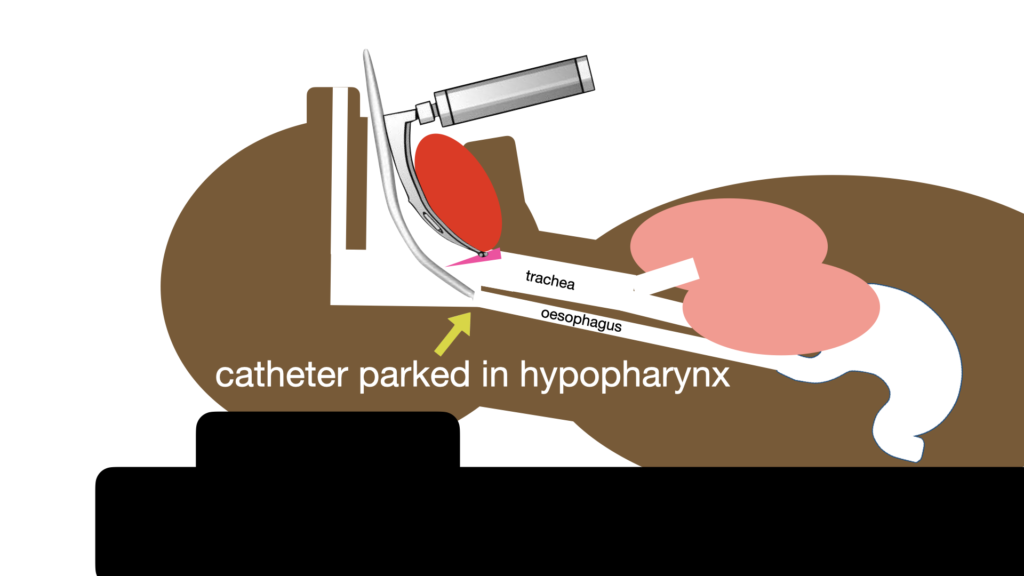

Trajectory 2 – Stuff coming UP – from the Respiratory Tract

This can result from haemoptysis or pulmonary oedema or drowning

This can be a major challenge. Particularly in pulmonary oedema, since suction just begets MORE pulmonary oedema, and you’ll be there all day trying to clear it.

What the patient needs is urgent tracheal intubation with a cuffed tube followed by positive pressure, including PEEP

Check out this intubation of a drowning case in which the double SALAD nightmare of gastric regurgitation AND frothy tracheal fluid is present. Note how the froth won’t stop until there is positive pressure ventilation via a cuffed tracheal tube:

Modifications or supplemental actions:

The trick here is to aim your bougie to the source of the froth when it is clear that it is of pulmonary origin.

One clever option is to place the suction catheter through the cords, disconnect the suction tubing from the catheter, and then advance the bougie through the suction catheter2. The catheter is then removed and a tracheal tube can be inserted over the bougie. Note that this is only described with the dedicated resuscitation suction catheter (DuCanto catheter).

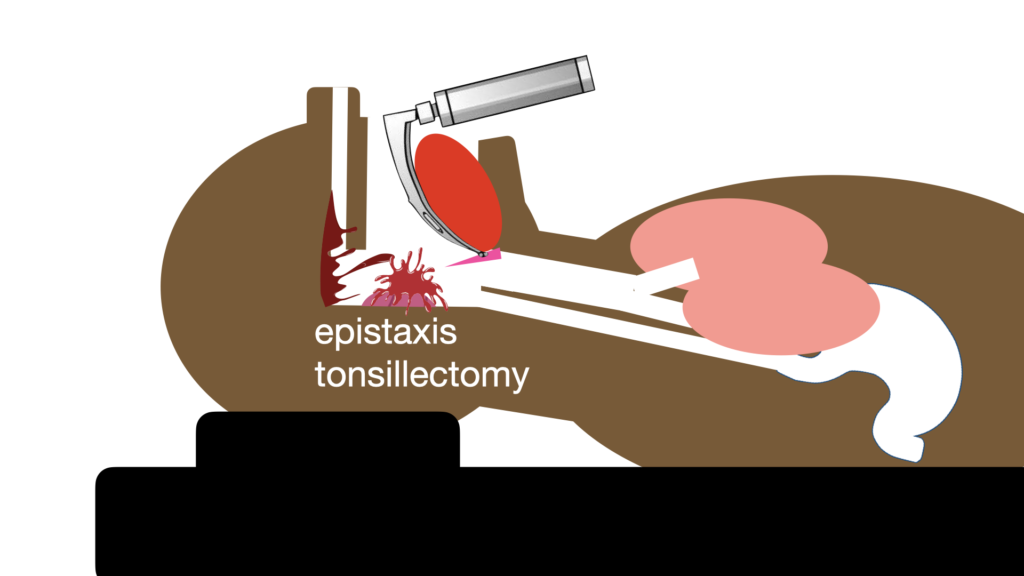

Trajectory 3 – Stuff coming DOWN – from the Upper Respiratory Tract

Here the contamination is usually a bleeding source, for example maxillo-facial haemorrhage, epistaxis, post-tonsillectomy bleed.

The suction is used to navigate to the larynx; it need not be parked deeply in the hypopharynx because the source is not from the oesophagus. This video is from a patient with severe epistaxis (there was another indication for intubation).

Modifications or supplemental actions:

Consider local haemorrhage control measures (eg. balloon tamponade for epistaxis).

Surprise trajectory 4 – In Situ Spontaneous Airway Contamination

Sometimes weird stuff just happens. In this video (courtesy of Sydney HEMS), an epiglottis abscess bursts during laryngoscopy, giving rise to unanticipated pus contamination:

Training

All serious critical care teams should train for airway contamination scenarios. Airway manikins can be modified using inexpensive parts available from DIY stores. Here’s one I built with my friend Dr Luca Ünlü:

An even less expensive version has been described using materials readily available in the operating theatre or emergency department3.

While most simulators replicate Trajectory 1 – stuff coming up from the GI Tract, you can be imaginative. To replicate the challenging drowned baby scenario, Luca and I built an infant pulmonary oedema trainer:

Summary

Jim DuCanto’s SALAD system has changed the game in critical care airway management. Teams now have a plan and a way of training for contaminated airway situations.

Consider that not all contaminated airway scenarios are identical. Remember the three trajectories of how the contaminant gets there, and how you might have to adjust your technique accordingly and add supplemental measures.

And in-situ spontaneous contamination can occur too if you’re lucky enough to see an epiglottic abscess erupt!

References

- Root CW, Mitchell OJL, Brown R, et al. Suction Assisted Laryngoscopy and Airway Decontamination (SALAD): A technique for improved emergency airway management. Resusc Plus. 2020 May 21;1-2:100005.

- Cochran-Caggiano N, Holliday J, Howard C. A Novel Intubation Technique: Bougie Introduction Via Ducanto Suction Catheter. J Emerg Med. 2024 Feb;66(2):221-224.

- Warburton D, Hartopp A. Creating an easy to construct, low-cost aspiration simulator for airway training. International Journal of Healthcare Simulation 2022;2(Suppl 1):A28