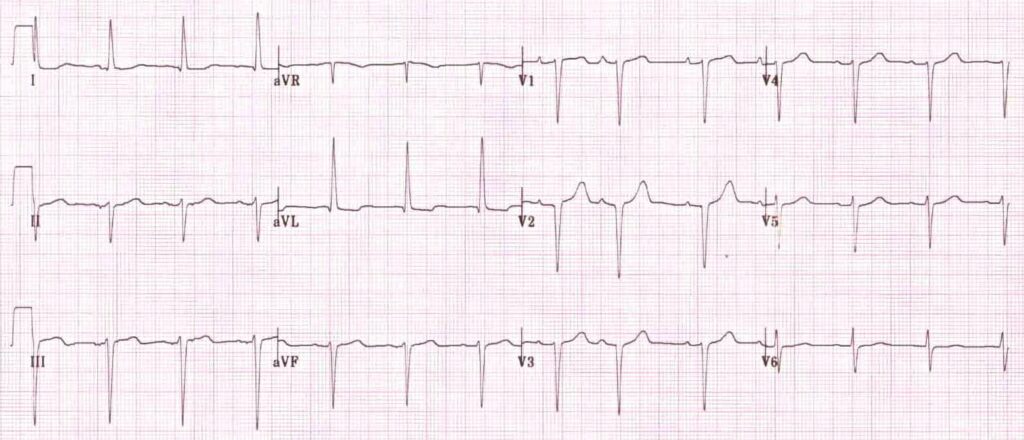

You ultrasound the chest of your shocked patient in resus with fluid refractory hypotension. You see fluid around the heart. The right ventricle keeps bowing inwards, which you recall being described as ‘a little invisible man jumping up and down using the RV as a trampoline’, and you know this is in fact a sign of right ventricular diastolic collapse.

The collapse of the right side of the heart during diastole is the mechanism for shock and cardiac arrest due to tamponade, because the high pericardial pressures prevent the right heart from filling in diastole. This patient therefore has ‘tamponade physiology’ on ultrasound. A quick scan of the IVC shows it is dilated and does not collapse with respiration. This confirms a high central venous pressure (as do the patient’s distended neck veins), also consistent with tamponade physiology.

A formal echo done in resus confirms your suspicion of a dliated aortic root and visible dissection flap, so the diagnosis is now clear. This is type A aortic dissection with tamponade. The patient remains hypotensive and mottled with increasing drowsiness. Cardiothoracic surgery is based at another hospital site 30 minutes away by ambulance.

As the critical care clinician responsible for, or assisting with this patient’s care (emergency physician, intensivist, anaesthetist, rural GP, physician’s assistant, etc.), how do we get this patient to definitive care and mitigate the risk of deterioration en route? Let’s discuss the options using real life case examples, and consider the physiology, the evidence, and the dogma.

Here are four key questions to consider:

1. To drain or not to drain the pericardium?

2. To intubate or not to intubate?

3. If they arrest – CPR or no CPR?

4. How to transfer – physician escort or just send in an ambulance on lights and sirens?

Here are three scenarios that follow the intial assessment of the above patient. They are based on similar cases shared with me by participants on the

Critical Care in the Emergency Department course.

Case 1

The patient is obtunded with profound shock and too unstable for transfer. The resus team undertakes pericardiocentesis and aspirates 30 ml of blood. The patient becomes conscious and cooperative and the systolic blood pressure (SBP) is 95 mmHg. The patient is transferred by paramedic ambulance to the cardothoracic centre where he is successfully operated on, resulting in a full recovery.

Case 2

As the patient is unconscious and requires interhospital transfer, the decision is made to intubate him for airway protection. He undergoes rapid sequence induction with ketamine, fentanyl, and rocuronium in the resus room. After capnographic confirmation of tracheal intubation he is manually ventilated via a self-inflating bag. The ED nurse reports a loss of palpable pulse and CPR is started. A team member suggests pericardiocentesis but a senior critical care physician says there is no point because ‘it won’t fix the underlying problem of aortic dissection’ and ’the blood will be clotted anyway’. After a brief attempt at standard ACLS, resuscitation efforts are discontinued and the patient is declared dead.

Case 3

The patient is hypotensive with a SBP of 90mmHg and drowsy but cooperative. The receiving centre has accepted the referral and an ambulance has been requested. The critical care physician responsible for patient transfers is requested to accompany the patient but declines, on the basis that ‘these cases are just like abdominal aortic aneurysms – they just need to get there asap. If they deteriorate en route we’re not going to do anything.’

The patient is transferred but 15 minutes into the journey he becomes unresponsive and loses his cardiac output. The transporting paramedics provide chest compressions and adrenaline/epinephrine but are unable to resuscitate him.

These cases illustrate some of the pitfalls and fallacies associated with tamponade due to type A dissection.

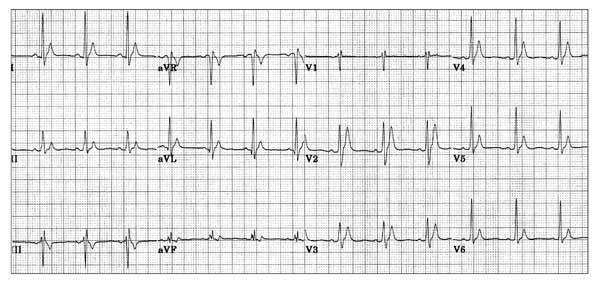

Pericardiocentesis

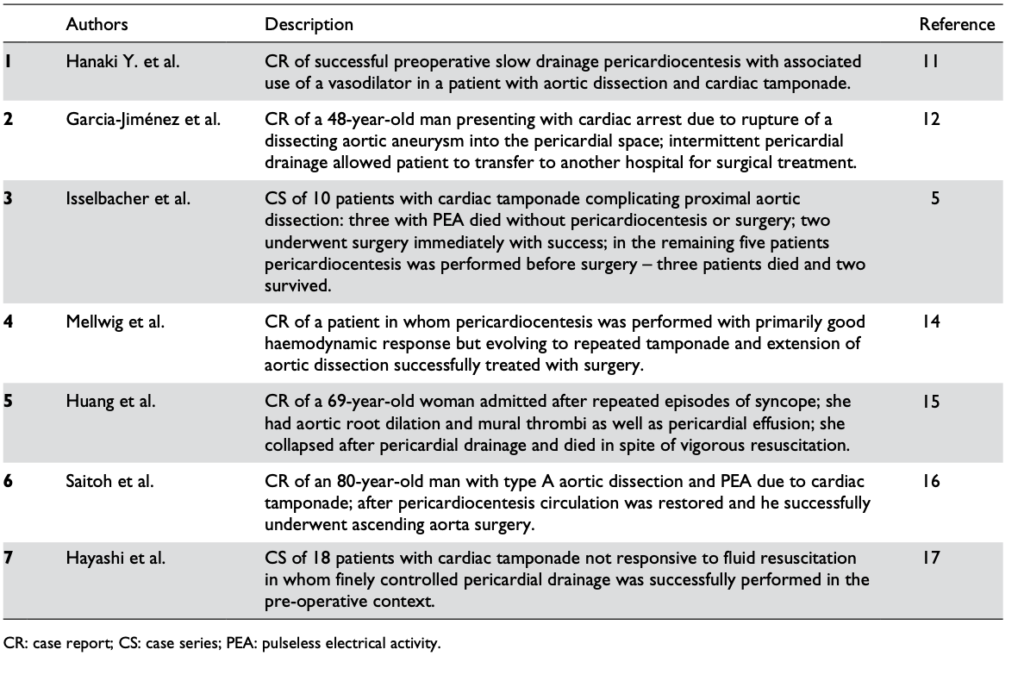

Pericardiocentesis can definitely be life-saving, restoring vital organ perfusion and buying time to get the patient to definitive surgery. Numerous case reports and case series provide evidence of its utility, even in patients in PEA cardiac arrest(1). The authors of the two largest cases series both used 8F pigtail drainage catheters(1,2).

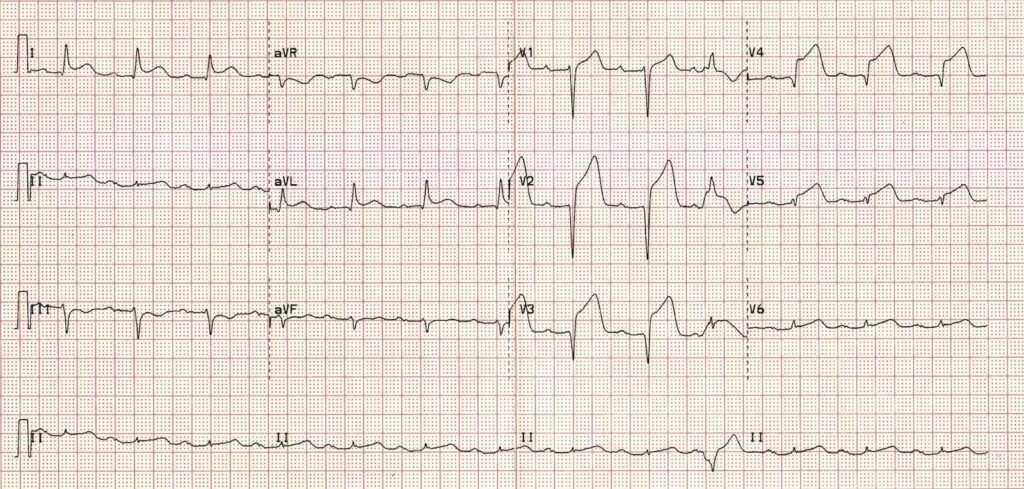

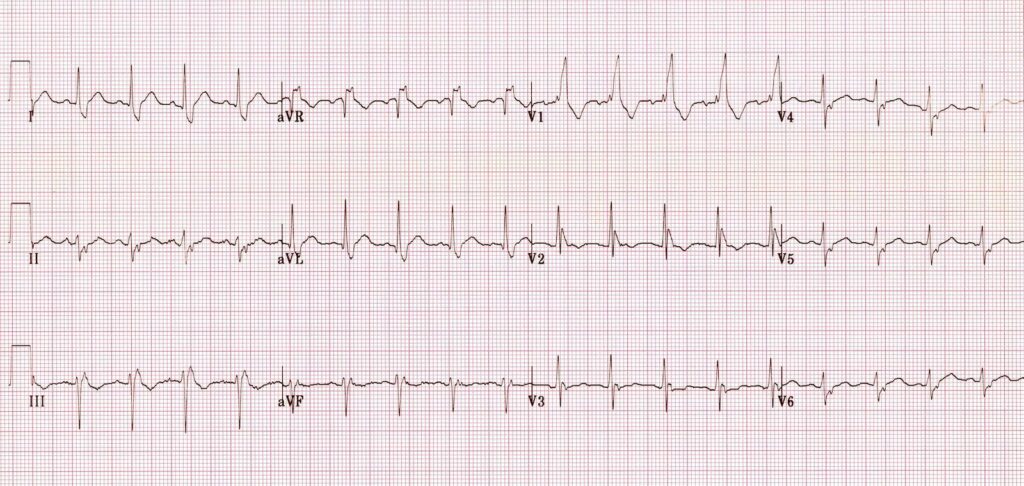

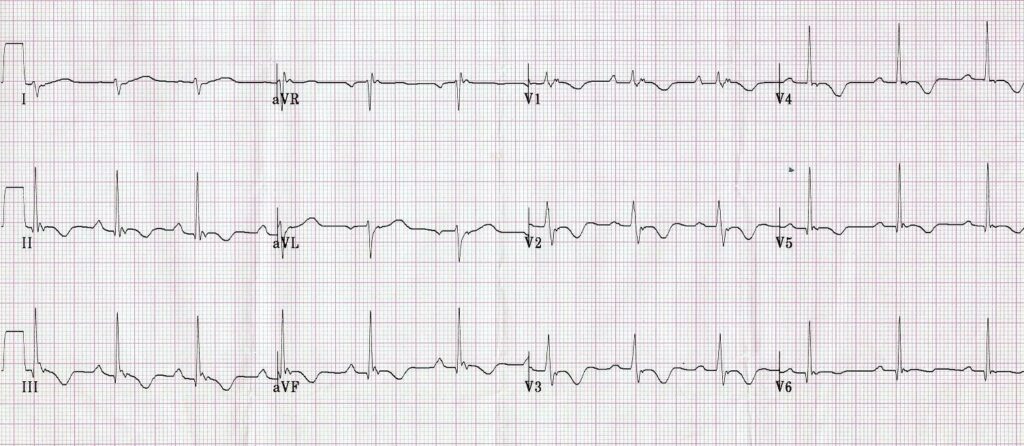

Reports in the literature regarding the pericardiocentesis of critical cardiac tamponade complicating aortic dissection from Cruz et al

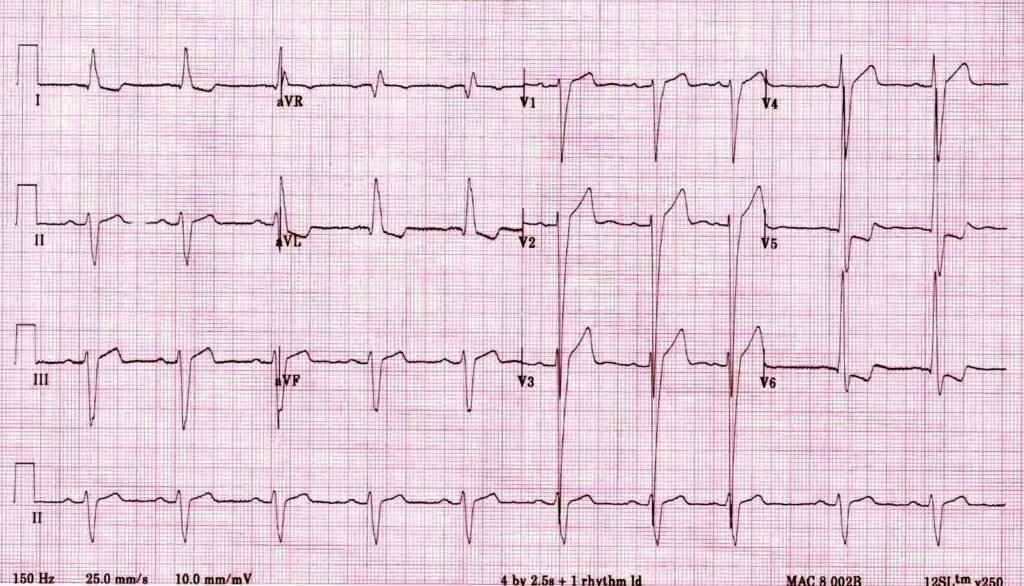

One key component of procedural success was controlled pericardial drainage, removing small volumes and reassessing the blood pressure, aiming for a SBP of 90 mmHg. The danger is overshooting, resulting in hypertension and extending the underlying aortic dissection which can be fatal (3).

“In the setting of aortic dissection with haemopericardium and suspicion of cardiac tamponade, emergency transthoracic echocardiography or a CT scan should be performed to confirm the diagnosis. In such a scenario, controlled pericardial drainage of very small amounts of the haemopericardium can be attempted to temporarily stabilize the patient in order to maintain blood pressure at 90 mmHg. (Class IIa, Level C)”

Intubation

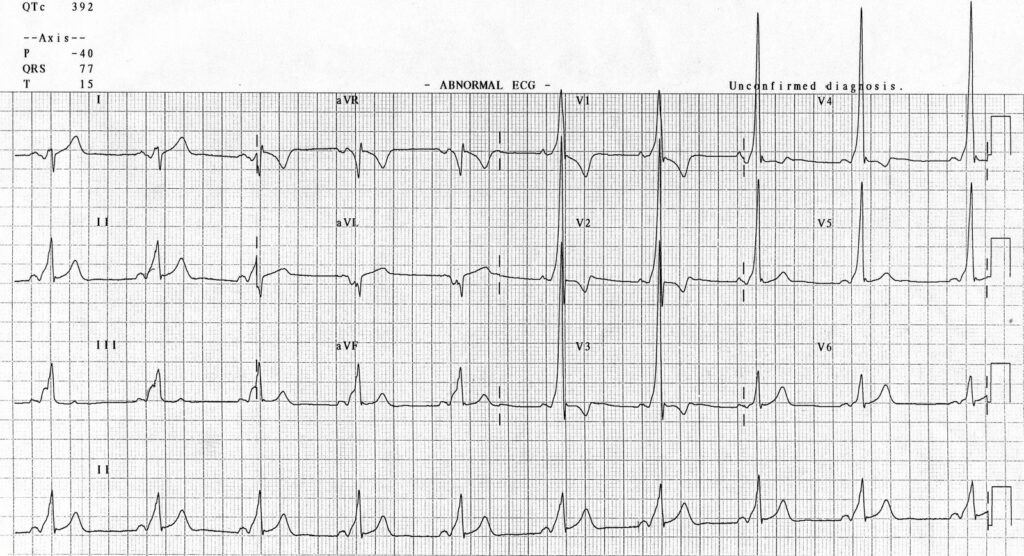

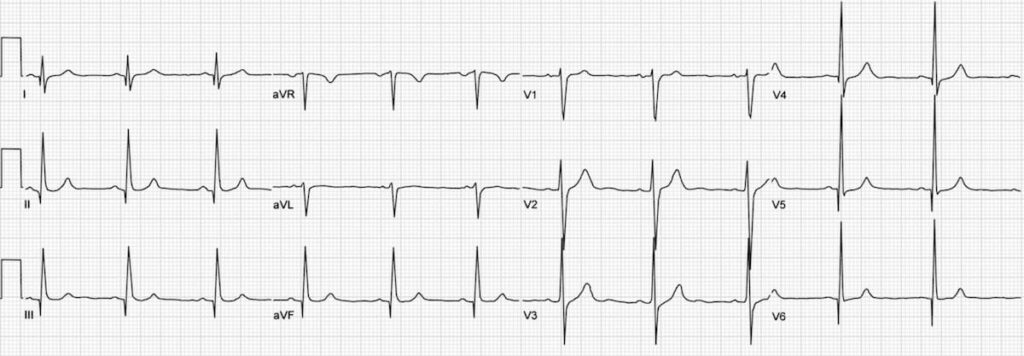

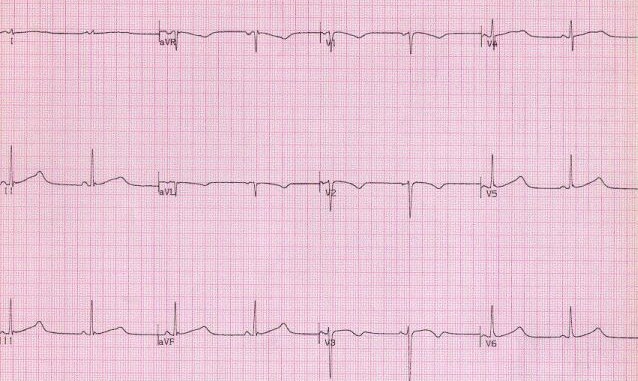

Deterioration of tamponade patients following intubation is well described in the literature and the risk is well appreciated by cardiothoracic anaesthetists(5).

Once positive pressure ventilation is started, positive pleural pressure is transmitted to the pericardium, where pressures can exceed right ventricular diastolic pressure and prevent cardiac filling. The result is a fall in and possible loss of cardiac output. This is further exacerbated by the addition of PEEP(6).

One suggested approach if the patient must be intubated for airway protection but is not yet in the operating room with a surgeon ready to cut, is to consider intubation under local anaesthesia and allow the patient to breathe spontaneously (maintaining negative pleural pressure) through the tube until the surgeon is ready to open the chest(5).

Alternatively preload with fluid, use cautious doses of induction agent, and ventilate with low tidal volumes and zero PEEP. However the patient can still crash, so remember that these effects of ventilation on cardiac output in tamponade can be mitigated by the removal of a relatively small volume of pericardial fluid(6).

Cardiac Arrest

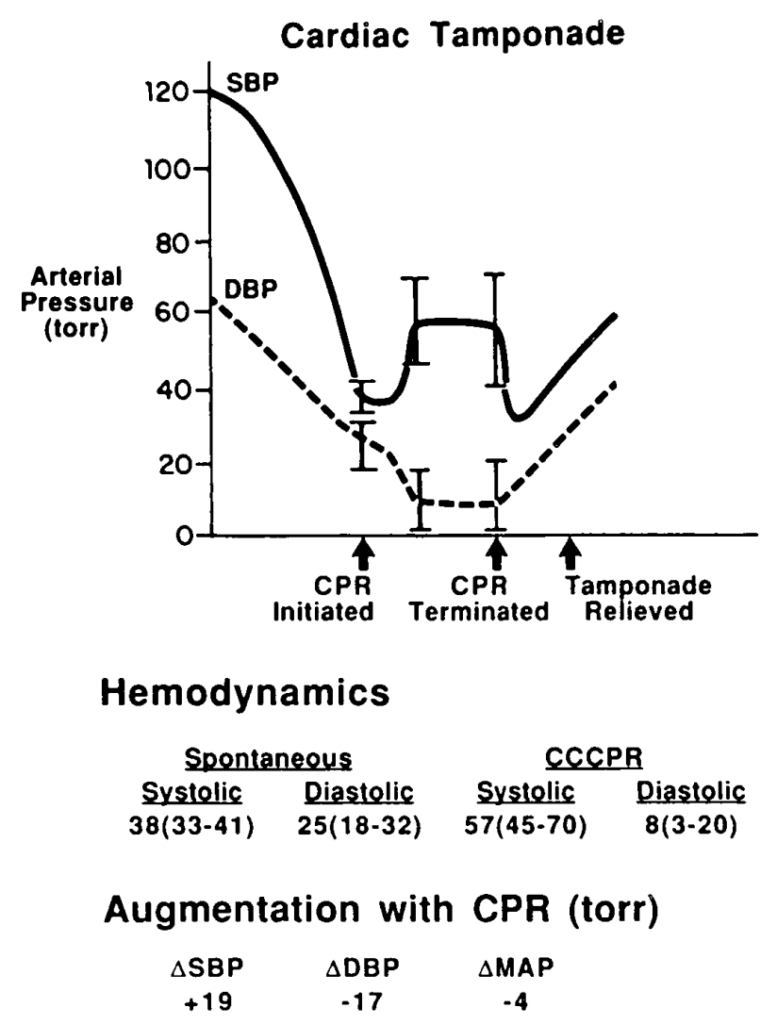

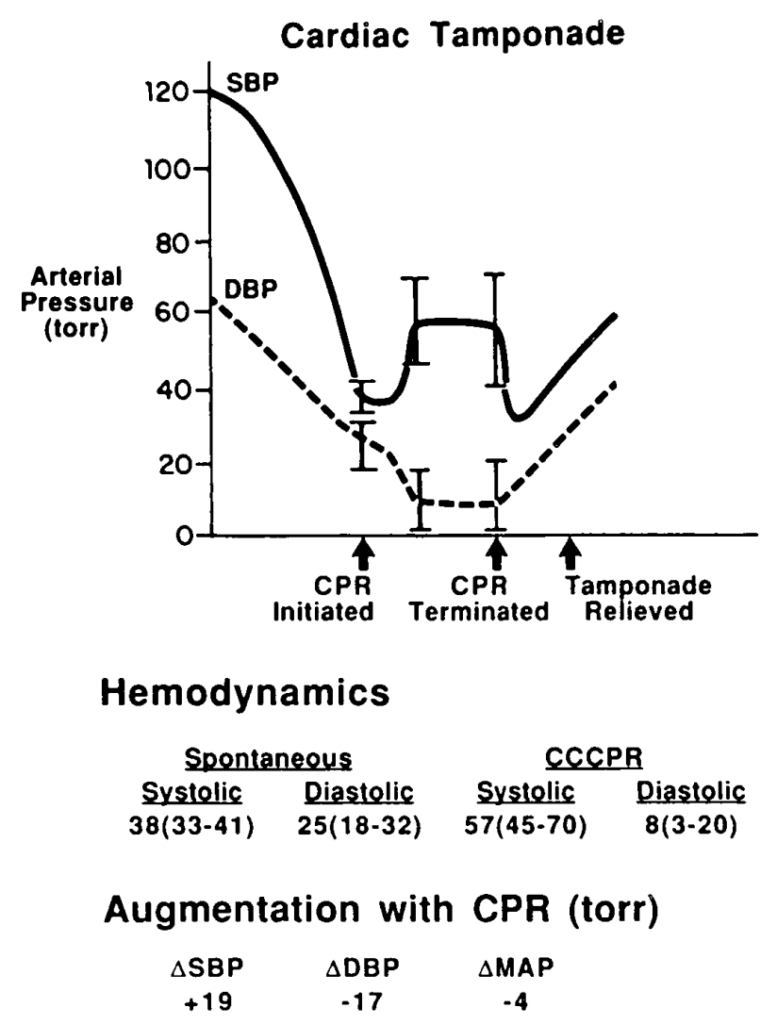

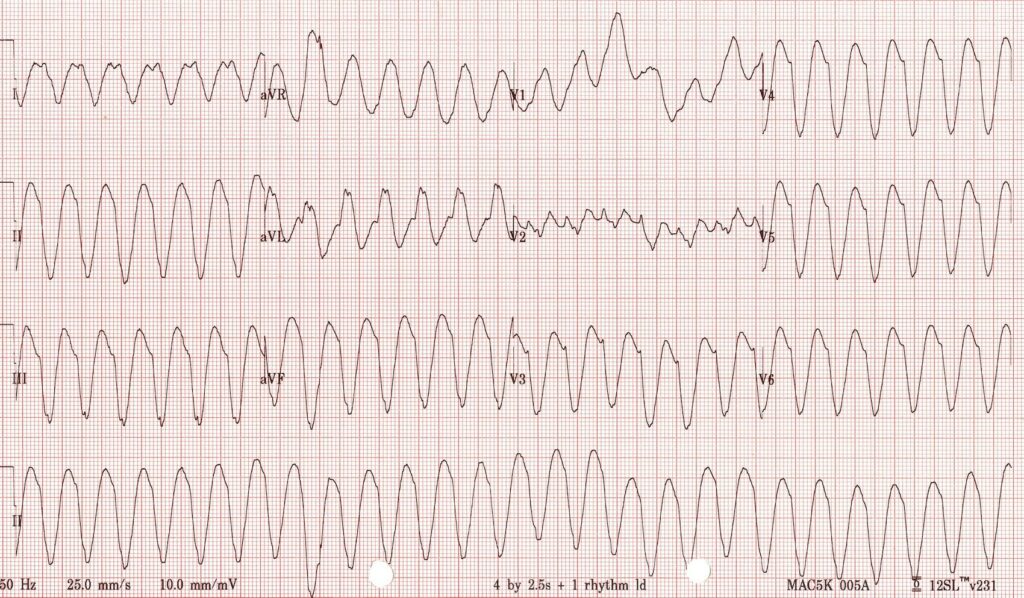

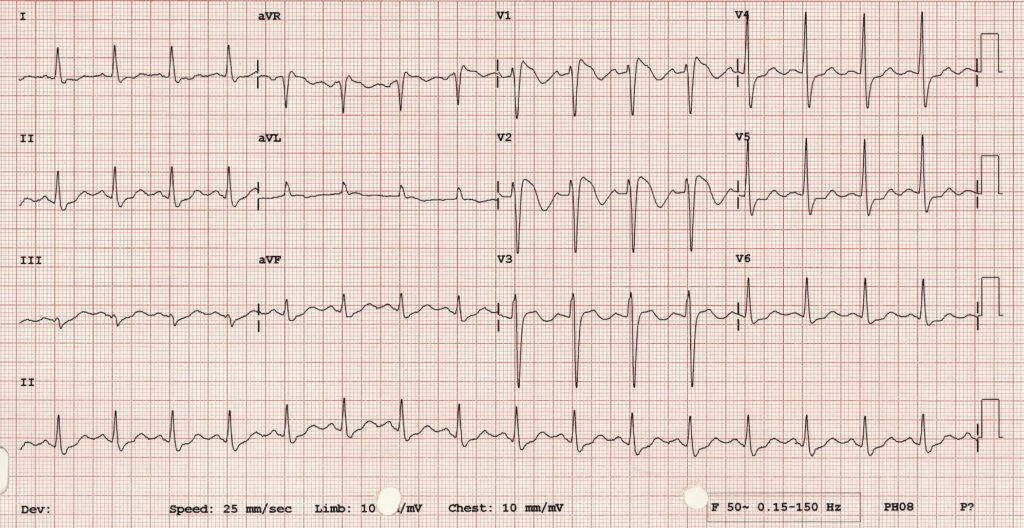

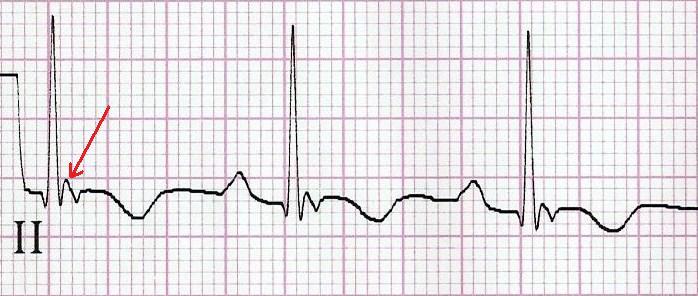

In cardiac arrest, external chest compressions are unlikely to be of benefit. In a study on baboons subjected to cardiac tamponade, closed chest massage resulted in an increase in intrapericardial pressure. There was an increase in systolic pressure, but a marked decrease in diastolic pressure, with an overall decrease in mean arterial pressure(7).

Pressure changes from CPR during tamponade in baboons. From Luna et al (7)

This would lead to impaired coronary perfusion and would be very unlikely to result in return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC). In the clinical situation described above, it is only relief of tamponade that is going to provide an arrested patient with a chance of recovery.

Transport

For patients with cardiac tamponade requiring interhospital (or intrahospital) transfer, it would seem vital therefore that the patient is accompanied by a clinician willing and capable to perform pericardiocentesis in the event of severe deterioriation or arrest en route. This simple life-saving intervention to deliver the patient alive to the operating room should be made available should the need arise.

Summary

- Patients presenting in shock from cardiac tamponade often have treatable underlying causes and represent a situation where the planning and actions of the resuscitationist can be truly life-saving.

- Pericardiocentesis is recommended in profound shock to buy time for definitive intervention. Controlled pericardiocentesis should be performed paying strict attention to SBP to avoid ‘overshooting’ to a hypertensive state in type A aortic dissection. In cardiac arrest, chest compressions are likely to be ineffective and pericardiocentesis is mandatory for ROSC.

- The institution of positive pressure ventilation often results in worsened shock or cardiac arrest, and this is exacerbated by PEEP. Where possible, avoid intubation until the patient is in the operating room, or use low tidal volumes and no PEEP. Even then pericardiocentesis may be necessary to maintain or restore cardiac output.

- Patients requiring transport who have tamponade should be accompanied by a clinician able to perform pericardiocentesis in the event of en route deterioration.

References

- Cruz I, Stuart B, Caldeira D, Morgado G, Gomes AC, Almeida AR, et al. Controlled pericardiocentesis in patients with cardiac tamponade complicating aortic dissection: Experience of a centre without cardiothoracic surgery. European Heart Journal: Acute Cardiovascular Care. 2015 Mar 19;4(2):124–8.

- Hayashi T, Tsukube T, Yamashita T, Haraguchi T, Matsukawa R, Kozawa S, et al. Impact of Controlled Pericardial Drainage on Critical Cardiac Tamponade With Acute Type A Aortic Dissection. Circulation. 2012 Sep 10;126(11_suppl_1):S97–S101.

- Isselbacher EM, Cigarroa JE, Eagle KA. Cardiac tamponade complicating proximal aortic dissection. Is pericardiocentesis harmful? Circulation. 1994 Nov 1;90(5):2375–8.

- Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, Badano L, Barón-Esquivias G, Bogaert J, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. European Heart Journal. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921–64.

- Ho AMH, Graham CA, Ng CSH, Yeung JHH, Dion PW, Critchley LAH, et al. Timing of tracheal intubation in traumatic cardiac tamponade: A word of caution. Resuscitation. 2009 Feb;80(2):272–4.

- Möller CT, Schoonbee CG, Rosendorff C. Haemodynamics of cardiac tamponade during various modes of ventilation. Br J Anaesth. 1979 May;51(5):409–15.

- Luna GK, Pavlin EG, Kirkman T, Copass MK, Rice CL. Hemodynamic effects of external cardiac massage in trauma shock. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 1989 Oct;29(10):1430–3.

‘Do what you said you were going to do – the high performance culture of excellence under pressure’ is the title of a talk by General John Jansen, organised by my friend

‘Do what you said you were going to do – the high performance culture of excellence under pressure’ is the title of a talk by General John Jansen, organised by my friend