This guest post from a fellow retrieval clinician contains a powerful message for us all. We have a responsibility to recognise the inevitability of clinician error, and to develop systems within our organisations to support those involved to avoid the ‘second victim’ phenomenon.

– 0:01: Error – Noun – A mistake

I was the picture perfect hire, I had tailored most of my career for our line of work: retrieval.

I was a senior FRU Paramedic with a background including the hottest terms: “clinical development”, “ultrasound”, “research”, “educator” and the useless alphabet soup that one inevitably acquires through enough time in healthcare. My CV was mint, printed on subtly thick paper to give a subliminal message of “excellence” – calculated moves for a calculated outcome.

I knew the protocols, policies, procedures before stepping through the door. With a fantastic orientation behind me, I was fucking awesome. I was in the stratosphere of awesome. Flightsuit, the smell of Jet A, podcasts blaring. I approached the one-year mark in retrieval feeling at home. Being granted complete clinical autonomy, I found my work deeply rewarding, stimulating. Nitric Oxide, ECMO, Ketamine, DSI/RSI, TXAblahblahblah. The buzz of Twitter was my daily work.

“Error” was a word, a noun. Error was a picture of crashed airplanes or derailed trains. Droning Powerpoints featured the Swiss cheese model and non-sequitur diagrams with abstract buzz-words. If you sucked, you crashed and burned. If you were good, you landed on the goddamn Hudson River.

+ 0:01: I am Error

Through an error in medication transitions, a young girl died under my care. Regardless of the slew of contributing factors, the latent errors – I am Proximate Cause. That is a title that is hard to shed. That is a title that follows you through day and night, wakefulness and sleep, at work, in the car, in the shower, in bed.

Having lost my desire to return to work, I drafted a curt letter of resignation and began the search for work elsewhere where I might be free of consequence. I was filled with dread waiting for my pager to go off, whispering a prayer for an easy tasking. I lacked the organizational or personal tools to process the slew of emotions I felt – incompetence, inadequacy and guilt. Just as easily as I had woven myself into who I was, I came undone.

+ 0:02: “Error-Free” – Adjective – Containing no mistakes

Despite our best attempts to adopt the lessons of aviation, aerospace and high-stakes systems into our craft, we in retrieval are primed for error throughout the work we do every day. We dive into the currents of diagnostic momentum, wading through the thoughts of others. The chaos swirling around us leads to erosion of situational awareness and the interruption of processes. The unforgiving physiology of the critically ill also force us to tread close to the edge. The margins are razor-thin, the consequences are great.

Just like we prepare for the risks involved with a complex machine such as the helicopter, we must train for the consequences of the complexities of medicine, such as error.

Our teams train for the very remote risk of over-water ditching through egress training yet little time is spent on a constant danger to our teams and our patients. The injection of simulated error through misdiagnoses, human factors and poorly labeled vials can not only prime the team for the capture of potential error but also the very real emotions that can result from mistakes – simulated or not. Much discussion has been had on resiliency training as of late, much of its focus on preparing teams for success in the midst of crisis. We must train for events such as an error like mine to prepare the individual clinician for the crisis that follows.

Yet the burden should not fall squarely on the individual clinician. As high performing organizations we have a duty to put in place transparent processes that can provide clinicians with support following a mistake as well as a clarity about “what comes next” following a mistake. As I consider my subsequent hardship following the death of this child, much of it took root in the lack of support from my organization and a lack of clarity about what would happen as a result of all this. More damaging than anything else is the solitude that comes with being unable to share one’s experience. A “second victim” left to their own devices to cope with their mistake is a victim of a system that has failed them.

We are equally primed for injury. One of your greatest strengths becomes your Achilles heel. We pursue our passions and find that resus and retrieval is the medicine that stimulates the cortex. This work inevitably becomes a fundamental part of who we are. The pursuit of excellence under the demanding conditions of our work is all-consuming, leading to this work become the very mesh of our being – “The Retrievalist” “The Resuscitationist.”

Following error, we experience an unraveling of who we are. The hard fall to the bottom is hard to recover from. I write this to let you know that it gets better and that you’re not alone. The resignation letter is deleted, the bottles stop emptying, the sleep comes more easily and you accept that in our craft, “error-free” is just a word, an adjective and that “error” is a noun and does not define you.

Above HEMS image credit: Dr Fiona Reardon

Related Resources:

“All Alone on Kangaroo Island” by Tim Leeuwenburg

“Medical Error” by Simon Carley

Unarguably the best lecture of the day was delivered by our very own

Unarguably the best lecture of the day was delivered by our very own

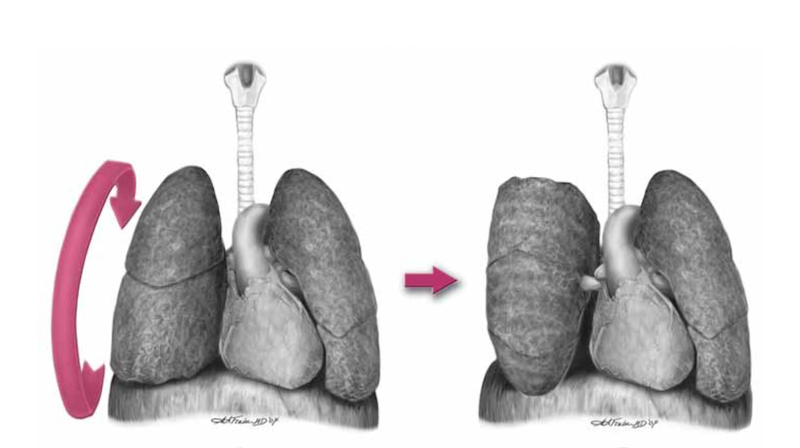

Microwaves seem to be the future if diagnostic testing. This modality is fast, is associated with a radiation dose lower than that of a mobile phone, non invasive, portable and has been shown to provide good information. It can be used on heads for intracranial haemorrhage and stroke or chests for pneumothorax detection. It’s all in the early stages but seems like it will be a viable option in the future.

Microwaves seem to be the future if diagnostic testing. This modality is fast, is associated with a radiation dose lower than that of a mobile phone, non invasive, portable and has been shown to provide good information. It can be used on heads for intracranial haemorrhage and stroke or chests for pneumothorax detection. It’s all in the early stages but seems like it will be a viable option in the future.