The London Trauma Conference remains up there on my list of ‘must go’ conferences to attend. It marks the end of the year, fills me with hope and inspires me for the future. Unfortunately this year I was torn between the conference and the demands of clinical directorship so I could only get to the “Air Ambulance & Prehospital Care Day”. At least this way I’m saved from the dilemma of which sessions to attend!

So what were the highlights of the Prehospital Day? For me, they were Prehospital ECMO,’Picking Up the Pieces’, and the REBOA update.

Prehospital ECMO

Professor Pierre Carli gave us an update on prehospital ECMO. Professor Carli (not to be confused with the equally awesome Professor Carley) is the medical director of Service d’Aide Médicale Urgente (SAMU) in Paris. They’ve been doing prehospital ECMO in Paris since 2011 and the data analysed over three years reveals a 10% survival to hospital discharge rate. We know from the work in Asia that successful outcome following traditional cardiac arrest management and ECPR is related to the speed of the intervention. Transposing the time to intervention from his 2011 – 2013 data onto the survival curve that Chen et al produced explains why the success rate is limited:

The revised 2015 process aims to reduce the duration of CPR, reduce time to ECMO and therefore improve survival to discharge rates. They are doing this by dispatching the ECMO team earlier.

The eligibility criteria for ECPR is also changing; patients >18 and <75years, refractory cardiac arrest (defined as failure of ROSC after 20min of CPR), no flow for < 5 minutes with shockable rhythm or signs of life or hypothermia or intoxication, EtCO2 > 10mmHg at time of inclusion and no major comorbidity.

Already there appears to be an improvement with 16 patients treated using the revised protocol with 5 survivors (31%) – although we must be wary of the small numbers.

A concern that was expressed by the French Department of Health was the fear of a reduction in organ donation with the introduction of ECPR – it turns out that rates have remained stable. In fact the condition of non heart beating donated organs is better when ECMO has been instigated; the long term effects on organ donation are being assessed.

I’m without doubt that prehospital ECMO/ED ECMO is the future although currently in the UK our hospital systems aren’t ready for this. If you want to learn more then look at the ED ECMO site or book on one of the many emerging courses on ED ECMO including the one that is run by Dr Simon Finney at the London Trauma Conference, or if you want to go further afield you could try San Diego (although places are fully booked on the next course).

Picking Up the Pieces

The Keynote speaker was Professor Sir Simon Wessely. He is a psychiatrist with a specialist interest in military psychology and his brief was to describe to us the public response to traumatic incidents. He has worked with the military and in civilian situations. After the 7/7 London bombings the population of London was surveyed: those most likely to be affected were of lower social class, of Muslim faith, those that had a relative that was injured, those unsure of the safety of others, those with no previous experience of terrorism and those experiencing difficulty in contacting others by mobile phone. Obviously there are many factors that we cannot influence however on the basis of the last risk factor our response to incidents has changed – the active discouragement to make phone calls has been changed to a recommendation of making short calls to friends and relatives.

The previous practice of offering immediate psychological debriefing to those involved in incidents was discounted by Prof Wessely – his research demonstrated that this intervention was not only not required but could actually result in harm: only a minority have ongoing psychological distress that can benefit from formal psychological input, which should occur later.

The approach that should be taken is to allow that individual to utilise their own social networks (family, friends, and colleagues) and to accept that in some cases the individual may not want or need to talk. This has led to the development of the Trauma Risk Management (TRIM) system which provides individuals within organisations that are exposed to traumatic events the skills required to identify those at risk of developing psychological problems and to recognise the signs and symptoms of those in difficulty. To a certain extent we naturally do this for our peers – I have spent many a night sitting in the ‘Good Samaritan’ pub with colleagues from the Royal London Hospital and London’s Air Ambulance – but having a more formal system is probably of benefit to enable those who have ongoing difficulties to access additional support.

REBOA update

Finally, the REBOA update – Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta. One year on, Dr Sammy Sadek informed us that there are now more courses teaching the REBOA technique than there are (prehospital) patients that have received it. Over the last year only seven patients have qualified for this intervention in London, far fewer than they had anticipated. Another three patients died before REBOA could be instigated. All patients had a positive cardiovascular response. Four of the seven died from causes other than exsanguination. Is it worth all the effort and resource to deliver this intervention when such a select group will benefit?

Obviously there was much more covered in the day, this is just a taste. If you’ve never been to the London Trauma Conference then I definitely would recommend it and even if you have been before there are so many breakout sessions now there is always something for everyone.

More on the London Trauma Conference:

- Keep an eye on the LTC website for information on the 2016 conference.

- Follow the #LTC2015 Twitter feed

- Read and listen to the excellent summaries at St Emlyn’s

Merry Christmas and see you next year!

Louisa Chan

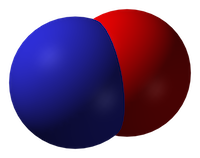

The use of inhaled nitric oxide is established in certain groups of patients: it improves oxygenation (but not survival) in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome(1), and it is used in neonatology for management of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn(2). But it can be applied in other resuscitation settings: in arrested or peri-arrest patients with pulmonary hypertension.

The use of inhaled nitric oxide is established in certain groups of patients: it improves oxygenation (but not survival) in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome(1), and it is used in neonatology for management of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn(2). But it can be applied in other resuscitation settings: in arrested or peri-arrest patients with pulmonary hypertension.