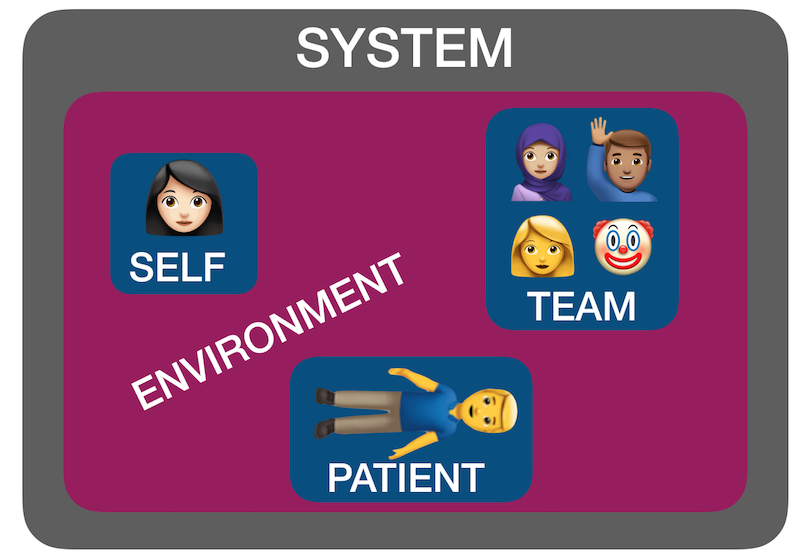

Occasionally we step out of the resuscitation room feeling like a case should have gone better, but it can be hard to put our finger on just where it went wrong. In my last post I discussed the STEPS approach to analysing resuscitation cases: Self, Team, Environment, Patient and System.

Occasionally you can get a case where the STEPS seem to be aligned but things still feel bad. In which the outcome was unsatisfactory because the plan was wrong, or the team wasn’t able to execute the plan. Consider the following case.

On this occasion the team worked efficiently and communicated well under clear leadership. Everyone knew the plan and shared the mental model. The environment was well controlled and the patient had been swiftly moved to CT within 20 minutes of arrival. Thanks to simulation training the well rehearsed cardiac arrest resuscitation was conducted with precision and the team was able to rapidly access the thrombolytic and knew the correct dose.

By a quick STEPS analysis, this case appears to have gone as well as could be expected. Perhaps there is nothing to learn. Some you win, some you lose, no?

No. Autopsy revealed type A aortic dissection with pericardial tamponade.

The management may have been efficient but it failed to be effective. In other words, things were done right, but the right things weren’t done; they did the wrong things right.

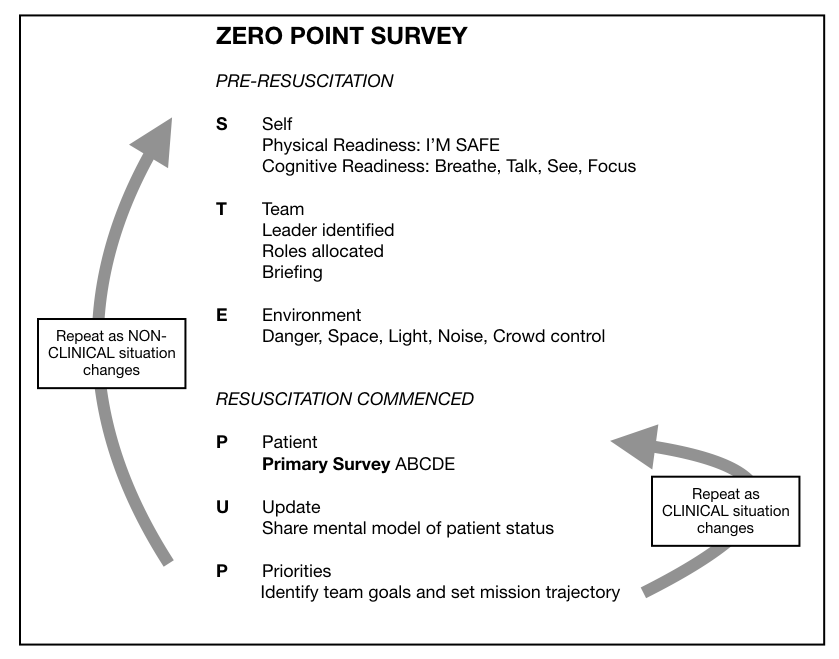

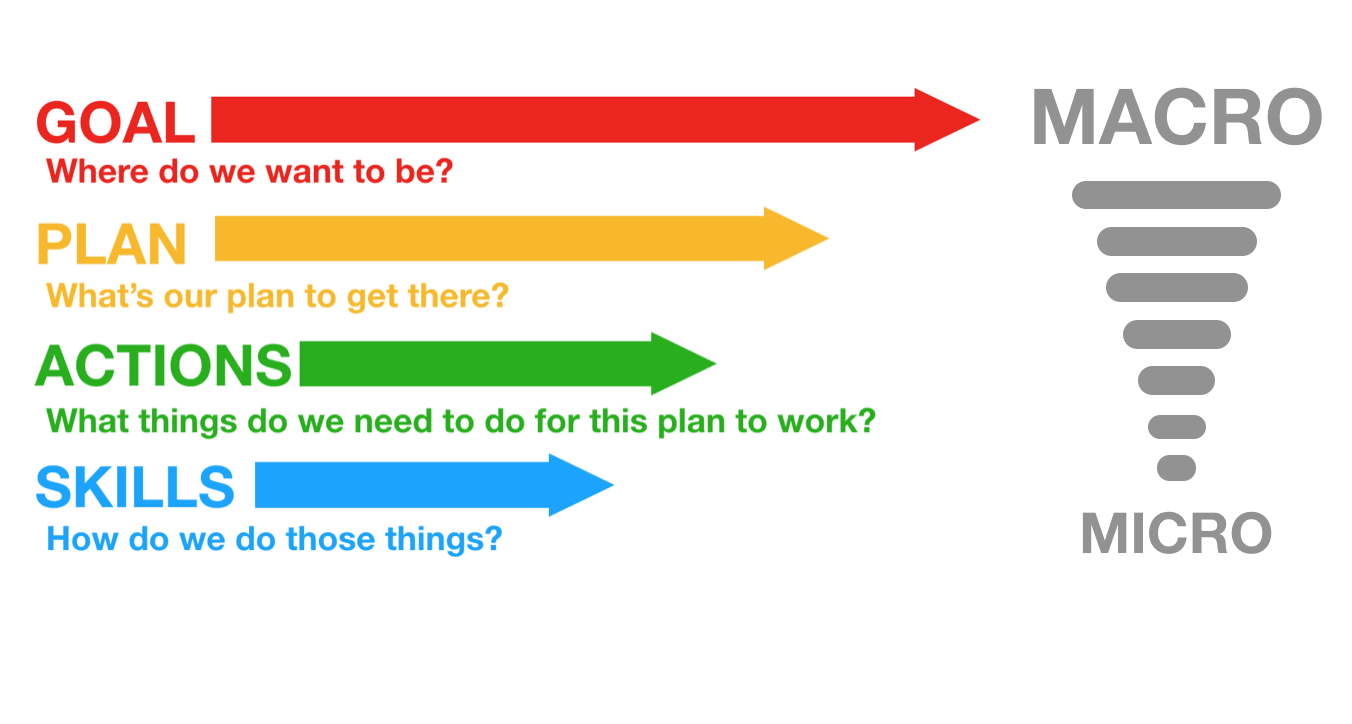

This might be an example where STEPS is inadequate, and instead we should evaluate the clinical trajectory. The cognitive bias that led to a lack of consideration of alternative diagnoses might be classifiable under ‘self’ or ‘team’ but I find it more helpful to consider it under a failure of strategy. What is strategy? Strategy in my mind is another word for plan. The plan is based on a particular resuscitation goal, and will consist of the procedures & skills required to action the plan. We can thus break down an attempted clinical trajectory into:

Goal (what are we trying to achieve)

Strategy, or Plan (what’s our plan to get there?)

Tactics, or Actions (what procedures will be required to execute the plan)

And, at more granular level: If we’re failing at the procedural level, the components of procedures, namely Skills & Microskills.

So, as we zoom in from macro to micro in setting the clinical trajectory, we can look at Goals, Plan, Actions, and Skills:

In the above case it appears the following was applied, in terms of Goal-Plan-Actions-Skills:

G – resuscitate hypotensive patient

P – give fibrinolysis for likely PE

A – consult respiratory physician, get CTPA

S – request scan, give heparin, transport to CT

The goal was appropriate, but the plan was ineffective.

The following approach would have been more effective.

G – resuscitate hypotensive patient

P – identify cause of undifferentiated hypotension and initiate treatment in the resus room

A – thorough bedside assessment in patient too sick to move: history, physical, CXR, ECG, labs, POCUS

S – Basic cardiac ultrasound

By planning to identify and treat the cause of hypotension in the resus room, the more appropriate investigation would have been selected (cardiac ultrasound) and the correct diagnosis is much more likely to have been made.

Let’s look at some other cases:

G – the goal – to provide maximally aggressive resuscitation – was not in keeping with the patient’s wishes. If the goal had been to provide care in accordance with his wishes, the plan could have included attempts to ascertain these sooner while providing initial treatment. Upon gaining sufficient information, a new goal can be established: maximising the patient’s comfort and dignity.

Goal – get her safely to the operating room

Plan – vascular access, cross match blood, start haemostatic resuscitation, go to OR as soon as possible

Actions – peripheral and/or intraosseous cannulation attempts

Skills – vascular access skills

Here the failure was at the actions and skills level. Better vascular access could have been attained using ultrasound guided peripheral cannulation, or central vascular access, or earlier intraosseous insertion.

Goal – Provide supportive care and minimise complications from overdose

Plan – Airway protection and admit to ICU for monitoring

Actions – Rapid sequence intubation, ICU referral

Skills – Pre-, peri- and post-intubation oxygenation techniques; patient positioning; rapid sequence induction of anaesthesia; direct laryngoscopy; bougie handling techniques; external laryngeal manipulation

In this case the patient was not placed in the ramped position and no nasal cannulae were applied for apnoeic oxygenation. A tube was railroaded over an oesophageal bougie, which arguably should not occur if ‘hold up’ is sought when the bougie is placed.

Although the goal, plan and actions were appropriate, the team did not demonstrate adequate skill in this procedure. Likely due to a failure of training, standardised procedures, and checklists (or their application), this could also be identified as a ‘system’ problem in STEPS. It is also possible that the intubator forgot her training under stress – a problem classifiable under ‘self’. Alternatively other members of the team may have had knowledge but didn’t speak up or cross-check their colleague, which would be a ‘team’ issue.

Limitations of this approach

This sort of analysis is retrospective and subjective and at risk of hindsight bias (e.g. distortion due to projection, denial, or selective recall). However, these limitations do not negate the value of the learning exercise, particularly if we are aware of them and strive to minimise their impact (e.g. write down the details of a cases as soon as possible afterward). It at least provides a structure for individuals and teams to begin the conversation about where and how things may have been suboptimal.

Goals may be multiple and may change according to incoming information, and for each goal there may be several viable alternative plans. STEPS and GPAS may overlap, eg. team failures may result in inappropriate goals and strategies, or in failed procedures.

Summary

These models may prove helpful as a means of dissecting a case in a structured way. Put simply, STEPS offers a structure for identifying efficiency improvements (“doing things right”) and GPAS can help us assess effectiveness (“doing the right things”).

Another way of looking at it is that STEPS provides the components of a resus at any point in time, and GPAS defines the trajectory: where the resus is going and how to get there.

I use this structure to analyse cases in my own clinical practice and in my teaching. I would be interested to hear from others’ experience. Do you find this approach useful in identifying areas for improvement in those cases that you feel should have gone better?

Thanks to Chris Nickson for his comments and improvements to this post