I want to clarify some terminology I use on a day-to-day basis, which is now so ingrained in my vocabulary that I forget that its meaning may not be obvious to all.

“You go in there and it looks like a chicken bomb has gone off…”

“..external muppet factors can delay preparation for transport”

Muppets

The first is ‘muppet’. This does not refer to the much loved and trademarked invention of Jim Henson, (and now property of Disney) – a word originally thought to be a synthesis of ‘marionette’ and ‘puppet’. If I were referring to these wonderful icons of children’s televisual theatre I would capitalise the ’m’. Nope. I refer to the British meaning, which the Oxford English Dictionary lists as: ‘an incompetent or foolish person’. However I apply it in the context of behaviour rather than character. A wealth of evidence has proven that good people can do bad things given the circumstances, and situational factors can lead us to behave in a way that we would not normally consider to be correct.

The first is ‘muppet’. This does not refer to the much loved and trademarked invention of Jim Henson, (and now property of Disney) – a word originally thought to be a synthesis of ‘marionette’ and ‘puppet’. If I were referring to these wonderful icons of children’s televisual theatre I would capitalise the ’m’. Nope. I refer to the British meaning, which the Oxford English Dictionary lists as: ‘an incompetent or foolish person’. However I apply it in the context of behaviour rather than character. A wealth of evidence has proven that good people can do bad things given the circumstances, and situational factors can lead us to behave in a way that we would not normally consider to be correct.

Certain situations can therefore lead our behaviour to at least appear to be incompetent or foolish. So perfectly good clinicians can appear to act like muppets during a resuscitation, given the circumstances. Various environmental and psychological factors contribute to this. Those factors generated within our own brains or bodies that influence our personal behaviour and performance have been called ‘internal muppet factors’. These include various cognitive errors such as inattention or fixation, or simple physiological stresses like fatigue or hunger. Those that relate to external forces such as environmental pressures or interaction with other team members are grouped under ‘external muppet factors’. These are most often a consequence of poor leadership and communication, and a lack of a shared mental model and agreed mission trajectory.

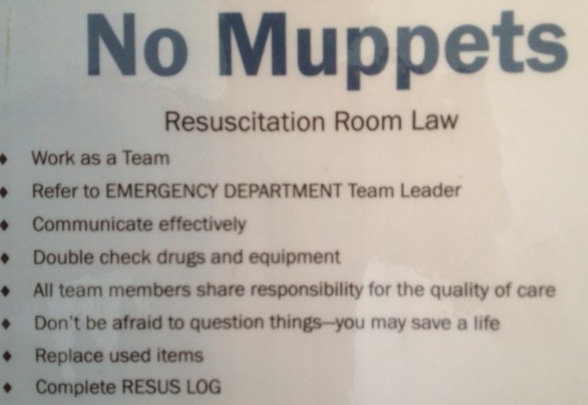

I had the privilege of working with Norwegian critical care doctor Per Bredmose, aka Viking One. He and I coined the terms internal and external muppet factors as a framework for debriefing resuscitation cases when attempting to understand the human factors involved. This was when we worked together in the UK in Basingstoke, where for the duration of my tenure we had a sign up on the wall in the resus room saying ‘No muppets’ (this now lives in my office in Sydney).

Chicken Bombs

When the external muppet factor is allowed to escalate unchecked, the end result is frenetic activity and noise from the staff without coordinated meaningful intervention for the patient. Comparisons with ‘headless chickens’ are often drawn. In particularly challenging scenarios, it can appear that the panic has swelled to such magnitude that it goes nova, as though the headless chickens have actually exploded, metaphorically filling the room with a gruesome blanket of giblets and a snowstorm of feathers, clouding ones ability to assess and manage the patient effectively. This high-point of group anxiety and ineffectiveness is what I mean by the term ’chicken bomb’, and I bet most readers of this blog will have witnessed the detonation of one.

When the external muppet factor is allowed to escalate unchecked, the end result is frenetic activity and noise from the staff without coordinated meaningful intervention for the patient. Comparisons with ‘headless chickens’ are often drawn. In particularly challenging scenarios, it can appear that the panic has swelled to such magnitude that it goes nova, as though the headless chickens have actually exploded, metaphorically filling the room with a gruesome blanket of giblets and a snowstorm of feathers, clouding ones ability to assess and manage the patient effectively. This high-point of group anxiety and ineffectiveness is what I mean by the term ’chicken bomb’, and I bet most readers of this blog will have witnessed the detonation of one.

I credit the invention of this term to emergency and prehospital physician James French, a master resuscitationist and human factors wizard who also introduced the idea of clinical logistics to us.

So, next time you encounter muppets and chicken bombs, feel free to use the terminology, although preferably not during an actual resus with those who might take it personally.