A case is reported in Prehospital Emergency Care1 in which an agitated patient (due to mania and alcohol intoxication) received 5 mg/kg (500 mg) of ketamine intramuscularly by an EMS crew which dissociated him within a few minutes. He subsequently developed episodes of laryngospasm in the emergency department which were unrelieved by head tilt, chin lift and simple airway adjuncts but responded to bag-mask ventilation (BMV). The patient was intubated because the laryngospasm recurred, although it had again responded to BMV.

The authors make the point that because of the response of laryngospasm to simple manoeuvres, and because in the prehospital environment a patient will not be left without an EMS provider present, ‘restricting ketamine to EMS units capable of rapid-sequence intubation therefore seems unnecessary.‘

This is one for EMS directors to consider seriously. Personally, I think practicing prehospital care without access to ketamine is like having a hand tied behind my back. Ketamine opens up a world of possibilities in controlling combative patients, optimising scene safety, providing sedation for painful procedures including extrication, and enabling severe pain to be controlled definitively.

I’ve been using ketamine regularly for prehospital analgesia and emergency department procedural sedation in both adults and kids for more than a decade. I’ve seen significant laryngospasm 5 times (twice in kids). On one of those occasions, a 3 year old child desaturated to around 50% twice during two episodes of laryngospasm. We weren’t slow to pick it up – that was just her showing us how quickly kids can desaturate which continued while we went through a stepwise approach until BMV resolved it. It was however an eye opener for the registrar (senior resident) assisting me, who became extremely respectful of ketamine after that. Our ED sedation policy (that I wrote) required that suxamethonium was ready and available and that an appropriate dose had been calculated before anyone got ketamine. Paralysis may extremely rarely be required, but when it’s needed you need to be ready.

Laryngospasm is rare but most regular prescribers of ketamine will have seen it; the literature says it occurs in about 1-2% of sedations, although anecdotally I think it’s a bit less frequent. Importantly for those weighing the risks of allowing non-RSI competent prescribers, the requirement for intubation is exceptionally rare (2 of 11,589 reported cases in one review). Anyone interested should read this excellent review of ketamine-related adverse effects provided by Chris Nickson at Life in The Fast Lane. Chris reminds us of the Larson manouevre, which is digital pressure in the notch behind and below the ear, described by Larson2 as follows:

The technique involves placing the middle finger of each hand in what I term the laryngospasm notch. This notch is behind the lobule of the pinna of each ear. It is bounded anteriorly by the ascending ramus of the mandible adjacent to the condyle, posteriorly by the mastoid process of the temporal bone, and cephalad by the base of the skull. The therapist presses very firmly inward toward the base of the skull with both fingers, while at the same time lifting the mandible at a right angle to the plane of the body (i.e., forward displacement of the mandible or “jaw thrust”). Properly performed, it will convert laryngospasm within one or two breaths to laryngeal stridor and in another few breaths to unobstructed respirations.

I use this point most often to provide painful stimuli when assessing GCS in a patient, particular those I think may be feigning unconsciousness (I’ve done this for a number of years since learning how painful it can be when I was shown it by a jujitsu instructor). Dr Larson says he was taught the technique by Dr Guadagni, so perhaps we should be calling it the ‘Guadagni manouevre’. The lack of published evidence has led to some appropriate skepticism3, but as it can be combined with a jaw thrust it needn’t delay more aggressive interventions should they become necessary, it may work, and it’s likely to be harmless.

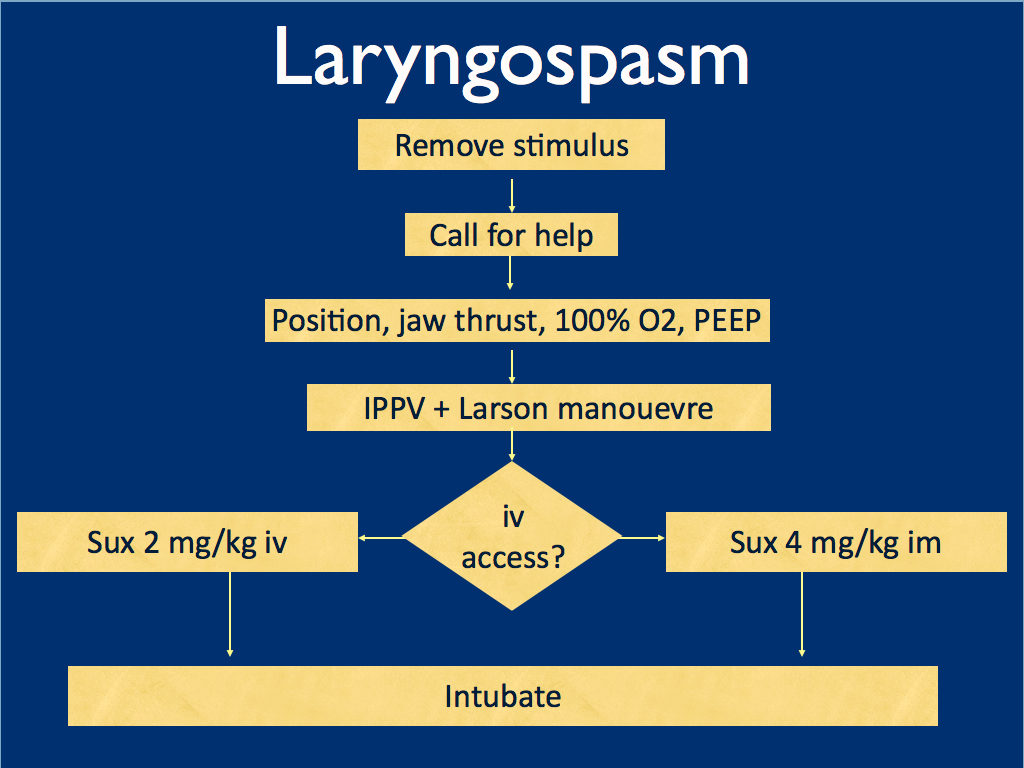

I presented the following suggested algorithm for management of laryngospasm during ketamine procedural sedation at a regional emergency medicine ‘Fellows Forum’ meeting in November 2007 in the UK. Since many paediatric procedural sedations were done using intramuscular (im) ketamine, it gives guidance based on whether or not vascular access has been obtained:

Some things I considered were:

-

- Neuromuscular blockade (NMB) isn’t always necessary – laryngospasm may be managed with other sedatives such as propofol. However, titrating further sedatives in a desaturating child in my view is inferior to definitive airway management and laryngeal relaxation with suxamethonium and a tube.

-

- Laryngospasm may be managed with much smaller doses of suxamethonium than are required for intubation – as little as 0.1 mg/kg may be effective. However, I think once we go down the NMB route we’re committed to intubation and therefore we should use a dose guaranteed to be effective in achieving intubating conditions.

-

- In the child without vascular access, I considered intraosseous and intralingual sux. However, intramuscular suxamethonium is likely to have a relaxant effect on the laryngeal muscles within 30-45 seconds, which has to be compared with time taken to insert and confirm intraosseous needle placement. I do not think the traditionally recommended intralingual injection has any role to play in modern airway management.

- At the time I wrote this most paediatric resuscitation bays in my area in the United Kingdom had breathing circuits capable of delivering PEEP – usually the Ayr’s T-Piece (specifically the Mapleson F system), which is why PEEP was included early in in the algorithm prior to BMV.

ABSTRACT An advanced life support emergency medical services (EMS) unit was dispatched with law enforcement to a report of a male patient with a possible overdose and psychiatric emergency. Police restrained the patient and cleared EMS into the scene. The patient was identified as having excited delirium, and ketamine was administered intramuscularly. Sedation was achieved and the patient was transported to the closest hospital. While in the emergency department, the patient developed laryngospasm and hypoxia. The airway obstruction was overcome with bag–valve–mask ventilation. Several minutes later, a second episode of laryngospasm occurred, which again responded to positive-pressure ventilation. At this point the airway was secured with an endotracheal tube. The patient was uneventfully extubated several hours later. This is the first report of laryngospam and hypoxia associated with prehospital administration of intramuscular ketamine to a patient with excited delirium.

1. Laryngospasm and Hypoxia After Intramuscular Administration of Ketamine to a Patient in Excited Delirium

Prehosp Emerg Care. 2012 Jul;16(3):412-4

2. Laryngospasm-The best treatment

Anesthesiology 1998; 89:1293-4

3. Management of Laryngospasm

http://www.respond2articles.com/ANA/forums/thread/1096.aspx