The use of inhaled nitric oxide is established in certain groups of patients: it improves oxygenation (but not survival) in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome(1), and it is used in neonatology for management of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn(2). But it can be applied in other resuscitation settings: in arrested or peri-arrest patients with pulmonary hypertension.

The use of inhaled nitric oxide is established in certain groups of patients: it improves oxygenation (but not survival) in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome(1), and it is used in neonatology for management of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn(2). But it can be applied in other resuscitation settings: in arrested or peri-arrest patients with pulmonary hypertension.

Read this (modified) description of a case managed by one of my resuscitationist friends from an overseas location:

She developed extreme pulmonary hypertension with suprasystemic pulmonary artery pressures, and she went down the pulmonary HT spiral as I stood there. On ultrasound her distended RV was making her LV totally collapse. She arrested. Futile CPR was started.

I have never had an extreme pulmonary HT survive an arrest. I grabbed a bag and rapidly set up a manual inhaled Nitric Oxide system and bagged and begged…

She achieved ROSC after some minutes. A repeat ultrasound showed a well functioning LV and less dilated RV.

Today, after 12 hours she is opening her eyes and obeying commands. Still a long way to go, but alive.

It sounds impressive. I don’t have more case details, and don’t know how confident they could be about the diagnosis of amniotic fluid embolism but the presentation certainly fits with acute pulmonary hypertension with RV failure. The use of inhaled nitric oxide has certainly been described for similar scenarios before(3). But it raises bigger questions: is this something we should all be capable of? Are there cardiac arrests involving or caused by pulmonary hypertension that will not respond to resuscitation without nitric oxide?

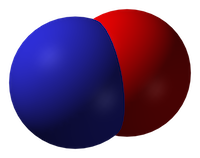

Nitric oxide

Inhaled nitric oxide is a pulmonary vasodilator. It decreases right-ventricular afterload and improves cardiac index by selectively decreasing pulmonary vascular resistance without causing systemic hypotension(4).

RV failure and pulmonary hypertension

Patients may become shocked or suffer cardiac arrest due to acute right ventricular dysfunction. This may be due to a primary cardiac cause such as right ventricular infarction (always consider this in a hypotensive patient with inferior STEMI, and confirm with a right ventricular ECG and/or echo). Alternatively it could be due to a pulmonary or systemic cause resulting in severe pulmonary hypertension, causing secondary right ventricular dysfunction. The commonest causes of acute pulmonary hypertension are massive PE, sepsis, and ARDS(5).

The haemodynamic consequences of RV failure are reduced pulmonary blood flow and inadequate left ventricular filling, leading to decreased cardiac output, shock, and arrest. In severe acute pulmonary hypertension the RV distends, resulting in a shift of the interventricular septum which compresses the LV and further inhibits LV filling (the concept of ventricular interdependence).

What’s wrong with standard ACLS?

In some patients with PHT who arrest, CPR may be ineffective due to a failure to achieve adequate pulmonary blood flow and ventricular filling. In one study of patients with known chronic PHT who arrested in the ICU, survival rates even for ventricular fibrillation were extremely poor and when measured end tidal carbon dioxide levels were very low. In the same study it was noted that some of the survivors had received an intravenous bolus administration of iloprost, a prostacyclin analogue (and pulmonary vasodilator) during CPR(6).

CPR may therefore be ineffective. Intubation and positive pressure ventilation may also be associated with haemodynamic deterioration in PHT patients(7), and intravenous epinephrine (adrenaline) has variable effects on the pulmonary circulation which could be deleterious(8).

If inhaled nitric oxide (iNO) can improve pulmonary blood flow and reduce right ventricular afterload, it could theoretically be of value in cases of shock or arrest with RV failure, especially in cases of pulmonary hypertension; these are patients who otherwise have poor outcomes and may not benefit from CPR.

Is the use of iNO described in shock or arrest?

Numerous case reports and series demonstrate recovery from shock or arrest following nitric oxide use in various situations of decompensated right ventricular failure from pulmonary hypertension secondary to pulmonary fibrotic disease(9), pneumonectomy surgery(10), and pulmonary embolism(11) including post-embolectomy(12).

Acute hemodynamic improvement was demonstrated following iNO therapy in a series of right ventricular myocardial infarction patients with cardiogenic shock(13).

A recent systematic review of inhaled nitric oxide in acute pulmonary embolism documented improvements in oxygenation and hemodynamic variables, “often within minutes of administration of iNO”. The authors state that these case reports underscore the need for randomised controlled trials to establish the safety and efficacy of iNO in the treatment of massive acute PE(14).

Why aren’t they telling us to use it?

If iNO may be helpful in certain cardiac arrest patients, why isn’t ILCOR recommending it? Actually it is mentioned – in the context of paediatric life support. The European Resuscitation Council states:

There is an increased risk of cardiac arrest in children with pulmonary hypertension.

Follow routine resuscitation protocols in these patients with emphasis on high FiO2 and alkalosis/hyperventilation because this may be as effective as inhaled nitric oxide in reducing pulmonary vascular resistance.

Resuscitation is most likely to be successful in patients with a reversible cause who are treated with intravenous epoprostenol or inhaled nitric oxide.

If routine medications that reduce pulmonary artery pressure have been stopped, they should be restarted and the use of aerosolised epoprostenol or inhaled nitric oxide considered.

Right ventricular support devices may improve survival

Should we use it?

So if acute (or acute on chronic) pulmonary hypertension can be suspected or demonstrated based on history, examination, and echo findings, and the patient is in extremis, it might be anticipated that standard ACLS approaches are likely to be futile (as they often are if the underlying cause is not addressed). One might consider attempts to induce pulmonary vasodilation to improve pulmonary blood flow and LV filling, improving oxygenation, and reducing RV afterload as means of reversing acute cor pulmonale.

Are there other pulmonary vasodilators we can use?

iNO is not the only means of inducing pulmonary vasodilation. Oxygen, hypocarbia (through hyperventilation)(15), and alkalosis are all known pulmonary vasodilators, the latter providing an argument for intravenous bicarbonate therapy from some quarters(16). Prostacyclin is a cheaper alternative to iNO(17) and can be given by inhalation or intravenously, although is more likely to cause systemic hypotension than iNO. Some inotropic agents such as milrinone and levosimendan can lower pulmonary vascular resistance(18).

What’s the take home message?

The take home message for me is that acute pulmonary hypertension provides yet another example of a condition that requires the resuscitationist to think beyond basic ACLS algorithms and aggressively pursue and manage the underlying cause(s) of shock or arrest. Inhaled pulmonary vasodilators may or may not be available but, as always, whatever resources and drugs are used, they need to be planned for well in advance. What’s your plan?

References

1. Adhikari NKJ, Dellinger RP, Lundin S, Payen D, Vallet B, Gerlach H, et al.

Inhaled Nitric Oxide Does Not Reduce Mortality in Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Regardless of Severity.

Critical Care Medicine. 2014 Feb;42(2):404–12

2. Steinhorn RH.

Neonatal pulmonary hypertension.

Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2010 Mar;11:S79–S84 Full text

3. McDonnell NJ, Chan BO, Frengley RW.

Rapid reversal of critical haemodynamic compromise with nitric oxide in a parturient with amniotic fluid embolism.

International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2007 Jul;16(3):269–73

4. Creagh-Brown BC, Griffiths MJ, Evans TW.

Bench-to-bedside review: Inhaled nitric oxide therapy in adults.

Critical Care. 2009;13(3):221 Full text

5. Tsapenko MV, Tsapenko AV, Comfere TB, Mour GK, Mankad SV, Gajic O.

Arterial pulmonary hypertension in noncardiac intensive care unit.

Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4(5):1043–60 Full text

6. Hoeper MM, Galié N, Murali S, Olschewski H, Rubenfire M, Robbins IM, et al.

Outcome after cardiopulmonary resuscitation in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension.

American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2002 Feb 1;165(3):341–4.

Full text

7. Höhn L, Schweizer A, Morel DR, Spiliopoulos A, Licker M.

Circulatory failure after anesthesia induction in a patient with severe primary pulmonary hypertension.

Anesthesiology. 1999 Dec;91(6):1943–5 Full text

8. Witham AC, Fleming JW.

The effect of epinephrine on the pulmonary circulation in man.

J Clin Invest. 1951 Jul;30(7):707–17 Full text

9. King R, Esmail M, Mahon S, Dingley J, Dwyer S.

Use of nitric oxide for decompensated right ventricular failure and circulatory shock after cardiac arrest.

Br J Anaesth. 2000 Oct;85(4):628–31. Full text

10. Fernández-Pérez ER, Keegan MT, Harrison BA.

Inhaled nitric oxide for acute right-ventricular dysfunction after extrapleural pneumonectomy.

Respir Care. 2006 Oct;51(10):1172–6 Full text

11. Summerfield DT, Desai H, Levitov A, Grooms DA, Marik PE.

Inhaled Nitric Oxide as Salvage Therapy in Massive Pulmonary Embolism: A Case Series.

Respir Care. 2012 Mar 1;57(3):444–8 Full text

12. Schenk P, Pernerstorfer T, Mittermayer C, Kranz A, Frömmel M, Birsan T, et al.

Inhalation of nitric oxide as a life-saving therapy in a patient after pulmonary embolectomy.

Br J Anaesth. 1999 Mar;82(3):444–7 Full text

13. Inglessis I, Shin JT, Lepore JJ, Palacios IF, Zapol WM, Bloch KD, et al.

Hemodynamic effects of inhaled nitric oxide in right ventricular myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock.

Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2004 Aug;44(4):793–8 Full text

14. Bhat T, Neuman A, Tantary M, Bhat H, Glass D, Mannino W, Akhtar M, Bhat A, Teli S, Lafferty J.

Inhaled nitric oxide in acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review.

Rev Cardiovasc Med 2015;16(1):1–8.

15. Mahdi M, Joseph NJ, Hernandez DP, Crystal GJ, Baraka A, Salem MR.

Induced hypocapnia is effective in treating pulmonary hypertension following mitral valve replacement.

Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2011 Jun;21(2):259-67

16. Evans S, Brown B, Mathieson M, Tay S.

Survival after an amniotic fluid embolism following the use of sodium bicarbonate.

BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014

17. Fuller BM, Mohr NM, Skrupky L, Fowler S, Kollef MH, Carpenter CR.

The Use of Inhaled Prostaglandins in Patients With ARDS: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.

Chest. 2015 Jun;147(6):1510–22 Full text

18. LITFL: Right Ventricular Failure

Further reading

Life In The Fast Lane iNO info

LITFL on Pulmonary Hypertension