ECG machines may give a printed report saying ***ACUTE MI***. In a retrospective study, patients on the ICU whose 12 lead ECGs contained this electronic interpretation did not have an elevated troponin 85% of the time. Even in the minority of patients whose electronic ECG diagnosis of MI was agreed with by a cardiologist, only one third developed an elevated troponin.

The authors state ‘In contrast to nonintensive care unit patients who present with chest pain, the electrocardiographic ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction diagnosis seems to be a nonspecific finding in the intensive care unit that is frequently the result of a variety of nonischaemic processes. The vast majority of such patients do not have frank ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.’

Electrocardiographic ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in critically ill patients: An observational cohort analysis

Crit Care Med. 2010 Dec;38(12):2304-230

Category Archives: ICU

Stuff relevant to patients on ICU

Massive haemorrhage guideline

The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland has published guidelines on the management of massive haemorrhage. Their summary:

- Hospitals must have a major haemorrhage protocol in place and this should include clinical, laboratory and logistic responses.

- Immediate control of obvious bleeding is of paramount importance (pressure, tourniquet, haemostatic dressings).

- The major haemorrhage protocol must be mobilised immediately when a massive haemorrhage situation is declared.

- A fibrinogen < 1 g.l)1 or a prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) of > 1.5 times normal represents established haemostatic failure and is predictive of microvascular bleeding. Early infusion of fresh frozen plasma (FFP; 15 ml.kg)1) should be used to prevent this occurring if a senior clinician anticipates a massive haemorrhage.

- Established coagulopathy will require more than 15 ml.kg)1 of FFP to correct. The most effective way to achieve fibrinogen replacement rapidly is by giving fibrinogen concentrate or cryoprecipitate if fibrinogen is unavailable.

- 1:1:1 red cell:FFP:platelet regimens, as used by the military, are reserved for the most severely traumatised patients.

- A minimum target platelet count of 75 · 109.l)1 is appropriate in this clinical situation.

- Group-specific blood can be issued without performing an antibody screen because patients will have minimal circulating antibodies. O negative blood should only be used if blood is needed immediately.

- In hospitals where the need to treat massive haemorrhage is frequent, the use of locally developed shock packs may be helpful.

- Standard venous thromboprophylaxis should be commenced as soon as possible after haemostasis has been secured as patients develop a prothrombotic state following massive haemorrhage.

Blood transfusion and the anaesthetist: management of massive haemorrhage – full document

Left molar approach

The left molar approach is a technique to improve the view at laryngoscopy using a standard macintosh laryngoscope. It was described by Yamamoto1 as follows:

- insert the blade from the left corner of the mouth at a point above the left molars;

- the tip of the blade is directed posteromedially along the groove between the tongue and the tonsil until the epiglottis and glottis come into sight;

- before elevating the epiglottis, the tip of the blade is kept in the midline of the vallecula and the blade is kept above the left molars;

- the view provided is framed by the flange, the lingual surface of the blade, and the tongue bulged to right of the blade.

The success of this approach in comparison with alternatives has been reproduced by others2. However although Yamamoto and others demonstrated that this improved the laryngoscopic view, actual intubation may still be difficult because of the limited access to the cords, in part caused by the bulging of the tongue.

Physicians from Turkey described a case3 of an unpredicted difficult airway to demonstrate that the use of the gum elastic bougie can facilitate intubation which had otherwise not been successful via the left molar approach.

The take home message for me is that if I have a grade IV view despite my usual first-pass success optimisation manoeuvres such as positioning, reducing or releasing cricoid pressure, and providing external laryngeal manipulation, it is worth trying the left molar approach in combination with a bougie to gain a view of the glottis and to pass the tube.

1. Left-molar Approach Improves the Laryngeal View in Patients with Difficult Laryngoscopy

Anesthesiology. 2000 Jan;92(1):70-4 Full Text

2. Comparative Study Of Molar Approaches Of Laryngoscopy Using Macintosh Versus Flexitip Blade

The Internet Journal of Anesthesiology 2007 : Volume 12 Number 1

3. The use of the left-molar approach for direct laryngoscopy combined with a gum-elastic bougie

European Journal of Emergency Medicine December 2010 ;17(6):355-356

Etomidate vs midazolam in sepsis

Given that single-dose etomidate can cause measurable adrenal suppression, its use in patients with sepsis is controversial. A prospective, double-blind, randomised study of patients with suspected sepsis who were intubated in the ED randomised patients to receive either etomidate or midazolam before intubation. The primary outcome measure was hospital length of stay, and no difference was demonstrated. The study was not powered to detect a mortality difference.

This study is interesting as a provider of fuel for the ‘etomidate debate’, but still irrelevant to those of us who have abandoned etomidate in favour of ketamine as an induction agent for haemodynamically unstable patients. Personally I remain unconvinced of the existence of patients who can’t be safely intubated using the limited choice of thiopentone or ketamine.

A Comparison of the Effects of Etomidate and Midazolam on Hospital Length of Stay in Patients With Suspected Sepsis: A Prospective, Randomized Study

Annals Emergency Medicine 2010;56(5):481-9

CVCs placed in the ED

Central lines in the ED are more likely to get infected because they’re inserted under less scrupulously aseptic conditions than in ICU, done more urgently, and are more likely to be placed in the mucky old femoral site by clumsy emergency physicians who don’t wash their hands after scratching their arses. Anyway, the intensivists will usually replace them with a ‘more ideal’ line after ICU admission. Right? Well, that’s what’s often taught and assumed to be the case, but a new study from a single centre suggests otherwise. ED-placed central venous catheters (19% of which were femoral) were typically left in for 4 to 5 days. The infection rate was 1.9 per 1,000 catheter-days, similar to that reported for central lines in other ICU case series.

Central lines in the ED are more likely to get infected because they’re inserted under less scrupulously aseptic conditions than in ICU, done more urgently, and are more likely to be placed in the mucky old femoral site by clumsy emergency physicians who don’t wash their hands after scratching their arses. Anyway, the intensivists will usually replace them with a ‘more ideal’ line after ICU admission. Right? Well, that’s what’s often taught and assumed to be the case, but a new study from a single centre suggests otherwise. ED-placed central venous catheters (19% of which were femoral) were typically left in for 4 to 5 days. The infection rate was 1.9 per 1,000 catheter-days, similar to that reported for central lines in other ICU case series.

Infection and Natural History of Emergency Department–Placed Central Venous Catheters

Annals of Emergency Medicine 2010;56(5):492-7

Rocuronium reusable after sugammadex

Sugammadex currently has no role in my own emergency / critical care practice. However a helpful paper informs us that patients whose rocuronium-induced neuromuscular blockade had been reversed by sugammadex may be effectively re-paralysed by a second high dose (1.2 mg/kg) of rocuronium. Onset was slower and duration shorter if the second dose of rocuronium was given within 25 minutes of the sugammadex.

The study was done with sixteen volunteers and the initial dose of roc was only 0.6 mg/kg – less than that used for rapid sequence intubation by many emergency & critical care docs.

When repeat dose roc was given five minutes after sugammadex (n=6), mean (SD) onset time maximal block was 3.06 (0.97) min; range, 1.92–4.72 min. For repeat dose time points ≥25 min after sugammadex (n=5), mean onset was faster (1.73 min) than for repeat doses <25 min (3.09 min) after sugammadex. The duration of block ranged from 17.7 min (rocuronium 5 min after sugammadex) to 46 min (repeat dose at 45 min) with mean durations of 24.8 min for repeat dosing <25 min vs 38.2 min for repeat doses ≥25 min.

Repeat dosing of rocuronium 1.2 mg kg−1 after reversal of neuromuscular block by sugammadex 4.0 mg kg−1 in anaesthetized healthy volunteers: a modelling-based pilot study

Br J Anaesth. 2010 Oct;105(4):487-92

Novel subclavian cannulation method

Ultrasound-guided subclavian vein cannulation has reduced complications, but there is still a high incidence of failure to cannulate the vein and of accidental arterial cannulation. Vassallo & Bennett noticed that a fast running intravenous infusion in the ipsilateral arm of a patient produced variable echogenicity (lighter echos) in the subclavian vein. They describe deliberately using this appearance to both identify the subclavian vein and differentiate it from the subclavian artery.

With the intravenous infusion running with frequent drips in the drip chamber, the ultrasound beam is placed in long axis to the subclavian vessels in the subclavicular position. The angle of the ultrasound beam is adjusted to reveal both the subclavian vein and artery. The variable echogenicity, together with compression, can then be used to identify the vein. The presence of variable echogenicity in the vessel gives continuous feedback that the ultrasound beam has not drifted onto the artery. In cases where the ultrasound beam has included both artery and vein in the same image, this method has clearly identified the intended target vessel.

Subclavian cannulation with ultrasound: a novel method

Anaesthesia, 2010;65:1041

Ketamine for HEMS intubation in Canada

Ketamine was used by clinical staff from the The Shock Trauma Air Rescue Society (STARS) in Alberta to facilitate intubation in both the pre-hospital & in-hospital setting (with a neuromuscular blocker in only three quarters of cases). Changes in vital signs were small despite the severity of illness in the study population.

A prospective review of the use of ketamine to facilitate endotracheal intubation in the helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS) setting

Emerg Med J. 2010 Oct 6. [Epub ahead of print]

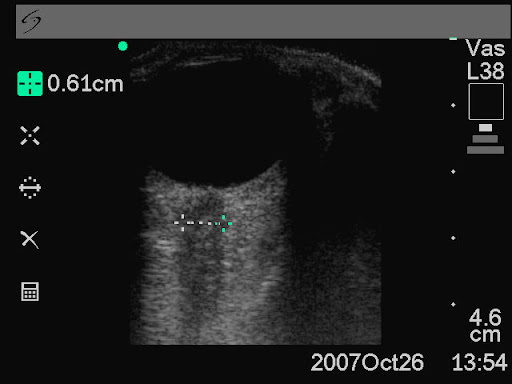

Ultrasound measurement of optic nerve sheath diameter

Here’s the abstract from a new study contributing the literature on ED assessment of raised intracranial pressure using ocular ultrasound:

Background To assess if ultrasound measurement of the optic nerve sheath diameter (ONSD) can accurately predict the presence of raised intracranial pressure (ICP) and acute pathology in patients in the emergency department.

Methods This 3-month prospective observational study used ultrasound to measure the ONSD in adult patients who required CT from the emergency department. The mean ONSD from both eyes was measured using a 7.5 MHz ultrasound probe on closed eyelids. A mean ONSD value of >0.5 cm was taken as positive. Two radiologists independently assessed CT scans from patients in the study population for signs of raised ICP and signs of acute pathology (cerebrovascular accident, subarachnoid, subdural or extradural haemorrhage and tumour). Specificity, sensitivity and k values, for interobserver variability between reporting radiologists, were generated for the study data.

Results In all, 26 patients were enrolled into the study. The ONSD measurement was 100% specific (95% CI 79% to 100%) and 86% sensitive (95% CI 42% to 99%) for raised ICP. For any acute intracranial abnormality the value of ONSD was 100% specific (95% CI 76% to 100%) and 60% sensitive (95% CI 27% to 86%). k Values were 0.91 (95% CIs 0.73 to 1) for identification of raised ICP on CT and 0.84 (95% CIs 0.62 to 1) for any acute pathology on CT, between the radiologists.

Conclusions This study shows that ultrasound measurement of ONSD is sensitive and specific for raised ICP in the emergency department. Further observational studies are needed but this emerging technique could be used to focus treatment in unstable patients.

Ultrasound measurement of optic nerve sheath diameter in patients with a clinical suspicion of raised intracranial pressure

Emerg Med J. 2010 Aug 15. [Epub ahead of print]

Cirrhotic patients on ICU

The prognosis of cirrhotic patients with multiple organ failure is not universally dismal. A retrospective French study examined predictive factors of mortality and concluded: In-hospital survival rate of intensive care unit- admitted cirrhotic patients seemed acceptable, even in patients requiring life-sustaining treatments and/or with multiple organ failure on admission. The most important risk factor for in-hospital mortality was the severity of nonhematologic organ failure, as best assessed after 3 days. A trial of unrestricted intensive care for a few days could be proposed for select critically ill cirrhotic patients.

Cirrhotic patients in the medical intensive care unit: Early prognosis and long-term survival

Crit Care Med. 2010 Nov;38(11):2108-2116