Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients With Thoracic Aortic Disease have been published by a collaboration between a number of professional bodies including the American Heart Association.

Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients With Thoracic Aortic Disease

Circulation. 2010 Apr 6;121(13):e266-369 – free Full Text as PDF

HTML full text

Category Archives: Acute Med

Acute care of the medically sick adult

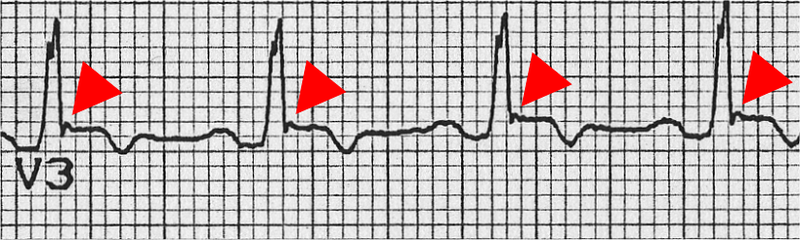

Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy/Dysplasia

This disease may result in sudden cardiac death in young people, and the assessment of patients who present with dysrhythmias or syncope should prompt a review of the ECG for suggestive features of Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy/Dysplasia (as well as ischaemia, conduction deficits, WPW syndrome, Brugada syndrome, and prolonged QT interval).

A Task force has revised its diagnostic criteria for the disease, listed as major and minor criteria pertaining to family history, ECG, echo, MRI, and angiographic features. The ECG features that front line doctors need to be on the look out for include:

- Inverted T waves in right precordial leads (V1, V2, and V3) or beyond in individual >14 years of age (in the absence of complete right bundle-branch block QR>120 ms)

- Inverted T waves in leads V1 and V2 in individual>14 years of age (in the absence of complete right bundle-branch block) or in V4, V5, or V6

- Inverted T waves in leads V1, V2, V3, and V4 in individual>14 years of age in the presence of complete right bundle-branch block

- Epsilon wave (reproducible low-amplitude signals between end of QRS complex to onset of the T wave) in the right precordial leads (V1 to V3)

- Nonsustained or sustained ventricular tachycardia of left bundle-branch morphology with superior axis (negative or indeterminate QRS in leads II, III, and aVF and positive in lead aVL)

- Nonsustained or sustained ventricular tachycardia of RV outflow configuration, left bundle-branch block morphology with inferior axis (positive QRS in leads II, III, and aVF and negative in lead aVL) or of unknown axis

- >500 ventricular extrasystoles per 24 hours (Holter)

Diagnosis of Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy/Dysplasia Proposed Modification of the Task Force Criteria

Circulation. 2010 Apr 6;121(13):1533-41

More info on this disease from the European Society of Cardiology here

Crystalloids vs colloids and cardiac output

It is said that when using crystalloids, two to four times more fluid may be required to restore and maintain intravascular fluid volume compared with colloids, although true evidence is scarce. The ratio in the SAFE study comparing albumin with saline resuscitation was 1:1.3, however.

A single-centre, single- blinded, randomized clinical trial was carried out on 24 critically ill sepsis and 24 non-sepsis patients with clinical hypovolaemia, assigned to loading with normal saline, gelatin 4%, hydroxyethyl starch 6% or albumin 5% in a 90-min (delta) central venous pressure (CVP)-guided fluid loading protocol. Haemodynamic monitoring using transpulmonary thermodilution was done each 30 min to measure, among other things, global end-diastolic volume and cardiac indices (GEDVI, CI). The reason sepsis was looked at was because of a suggestion in the SAFE study of benefit from albumin in the pre-defined sepsis subgroup.

Independent of underlying disease, CVP and GEDVI increased more after colloid than saline loading (P = 0.018), so that CI increased by about 2% after saline and 12% after colloid loading (P = 0.029).

Their results agree with the traditional (pre-SAFE) idea of ratios of crystalloid:colloid, since the difference in cardiac output increase multiplied by the difference in volume infused was three for colloids versus saline.

Take home message? Even though an outcome benefit has not yet been conclusively demonstrated, colloids such as albumin increase pre-load and cardiac index more effectively than equivalent volumes of crystalloid in hypovolaemic critically ill patients.

Greater cardiac response of colloid than saline fluid loading in septic and non-septic critically ill patients with clinical hypovolaemia

Intensive Care Med. 2010 Apr;36(4):697-701

Magnesium for subarachnoid haemorrhage

Symptomatic cerebral vasospasm occurs in nearly one-third of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and is a major cause of disability and mortality in this population.

Magnesium (Mg) acts as a cerebral vasodilator by blocking the voltage-dependent calcium channels.. Experimental studies suggest that Mg also inhibits glutamate release by blocking N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, decreases intracellular calcium influx, and increases red blood cell deformability; all these changes may reduce the occurrence of cerebral vasospasm and minimise brain ischemic injury occurring after SAH.

One hundred and ten patients within 96 hours of admission for aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) were randomised to receive iv magnesium or placebo. Nimodipine was not routinely given. Twelve patients (22%) in the magnesium group and 27 patients (51%) in the control group had delayed ischemic infarction – the primary endpoint (p< .0020; odds ratio [OR], 0.28; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.12– 0.64). Mortality was lower and neurological outcome better in the magnesium group but these results were not statistically significant.

Larger trials of magnesium in SAH are ongoing.

Prophylactic intravenous magnesium sulfate for treatment of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical study

Crit Care Med. 2010 May;38(5):1284-90

Update September 2012:

A multicentre RCT showed intravenous magnesium sulphate does not improve clinical outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage, therefore routine administration of magnesium cannot be recommended.

Magnesium for aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (MASH-2): a randomised placebo-controlled trial

Lancet 2012 July 7; 380(9836): 44–49 Free full text

[EXPAND Click to read abstract]

Background Magnesium sulphate is a neuroprotective agent that might improve outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage by reducing the occurrence or improving the outcome of delayed cerebral ischaemia. We did a trial to test whether magnesium therapy improves outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Methods We did this phase 3 randomised, placebo-controlled trial in eight centres in Europe and South America. We randomly assigned (with computer-generated random numbers, with permuted blocks of four, stratified by centre) patients aged 18 years or older with an aneurysmal pattern of subarachnoid haemorrhage on brain imaging who were admitted to hospital within 4 days of haemorrhage, to receive intravenous magnesium sulphate, 64 mmol/day, or placebo. We excluded patients with renal failure or bodyweight lower than 50 kg. Patients, treating physicians, and investigators assessing outcomes and analysing data were masked to the allocation. The primary outcome was poor outcome—defined as a score of 4–5 on the modified Rankin Scale—3 months after subarachnoid haemorrhage, or death. We analysed results by intention to treat. We also updated a previous meta-analysis of trials of magnesium treatment for aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. This study is registered with controlled-trials.com (ISRCTN 68742385) and the EU Clinical Trials Register (EudraCT 2006-003523-36).

Findings 1204 patients were enrolled, one of whom had his treatment allocation lost. 606 patients were assigned to the magnesium group (two lost to follow-up), 597 to the placebo (one lost to follow-up). 158 patients (26·2%) had poor outcome in the magnesium group compared with 151 (25·3%) in the placebo group (risk ratio [RR] 1·03, 95% CI 0·85–1·25). Our updated meta-analysis of seven randomised trials involving 2047 patients shows that magnesium is not superior to placebo for reduction of poor outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (RR 0·96, 95% CI 0·86–1·08).

Interpretation Intravenous magnesium sulphate does not improve clinical outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage, therefore routine administration of magnesium cannot be recommended.

[/EXPAND]

The early management of unstable angina and NSTEMI

The UK’s National Institute for Clinical Excellence has produced evidence based guidelines on the early management of unstable angina and NSTEMI

Their ‘key priorities for implementation’ are:

- As soon as the diagnosis of unstable angina or NSTEMI is made, and aspirin and antithrombin therapy have been offered, formally assess individual risk of future adverse cardiovascular events using an established risk scoring system that predicts 6-month mortality (for example, Global Registry of Acute Cardiac Events [GRACE]).

- Consider intravenous eptifibatide or tirofiban as part of the early management for patients who have an intermediate or higher risk of adverse cardiovascular events (predicted 6-month mortality above 3.0%), and who are scheduled to undergo angiography within 96 hours of hospital admission.

- Offer coronary angiography (with follow-on PCI if indicated) within 96 hours of first admission to hospital to patients who have an intermediate or higher risk of adverse cardiovascular events (predicted 6-month mortality above 3.0%) if they have no contraindications to angiography (such as active bleeding or comorbidity). Perform angiography as soon as possible for patients who are clinically unstable or at high ischaemic risk.

- When the role of revascularisation or the revascularisation strategy is unclear, resolve this by discussion involving an interventional cardiologist, cardiac surgeon and other healthcare professionals relevant to the needs of the patient. Discuss the choice of the revascularisation strategy with the patient.

- To detect and quantify inducible ischaemia, consider ischaemia testing before discharge for patients whose condition has been managed conservatively and who have not had coronary angiography.

- Before discharge offer patients advice and information about:

– their diagnosis and arrangements for follow-up

– cardiac rehabilitation

– management of cardiovascular risk factors and drug therapy for secondary prevention

– lifestyle changes

One of the most potentially confusing areas is the choice of antithrombin therapy. Whereas the low molecular weight heparin enoxaparin is currently widely used, the guideline recommends the following:

The guideline summary is here and the full guideline is here

International Carotid Stenting Study (ICSS)

Patients with symptomatic severe carotid artery stenosis do better with carotid endarterectomy than with medical therapy alone. Surgical complications such as bleeding and cranial nerve damage make the alternative strategy of carotid stenting attractive, but a new randomised trial of 1710 patients with over 50% stenosis and symptoms suggests otherwise.

In favour of stenting, there was one event of cranial nerve palsy in the stenting group compared with 45 in the endarterectomy group, and fewer haematomas of any severity in the stenting group than in the endarterectomy group (31 vs 50 events; p=0.0197).

However the incidence of stroke, death, or procedural myocardial infarction was 8.5% in the stenting group compared with 5.2% in the endarterectomy group (72 vs 44 events; HR 1.69, 1.16-2.45, p=0.006). Risks of any stroke (65 vs 35 events; HR 1.92, 1.27-2.89) and all-cause death (19 vs seven events; HR 2.76, 1.16-6.56) were higher in the stenting group than in the endarterectomy group. Three procedural myocardial infarctions were recorded in the stenting group, all of which were fatal, compared with four, all non-fatal, in the endarterectomy group.

The authors point out that longer term follow up remains to be looked at, but that carotid endarterectomy should remain the treatment of choice for symptomatic patients with severe carotid stenosis suitable for surgery. However most patients had no complications from either procedure and stenting is also likely to be better than no revascularisation in patients unwilling or unable to have surgery because of medical or anatomical contraindications.

Carotid artery stenting compared with endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis (International Carotid Stenting Study): an interim analysis of a randomised controlled trial

Lancet. 2010 Mar 20;375(9719):985-97

2000 vs 2005 VF guidelines: RCT

One of the key changes in international resuscitation guidelines between the 2000 and 2005 has been to minimise potentially deleterious hands-off time, so that CPR is interrupted less for pulse checks and DC shocks.

These two approaches have been compared in a randomised controlled trial of 845 patients in France requiring out of hospital defibrillation, in which the control group were shocked using AEDs with prompts based on the 2000 guidelines (3 stacked shocks before CPR resumed, and pulse checks done), and the intervention group were shocked using devices that prompted according to the 2005 guidelines, in which there were fewer and shorter intervals for which the AED required the rescuer to stay clear of the patient (single shocks, no pulse checks).

There was no difference in the primary endpoint of survival to hospital admission (43.2% versus 42.7%; p=0.87), or in survival to hospital discharge (13.3% versus 10.6%; p=0.19). The study was not powered to assess one year survival. In the authors’ words: “our randomized controlled trial now provides more definitive evidence that this combination of Guidelines 2005 CPR protocol changes does not measurably improve outcome. Although the protocol changes accomplish the desired effect of increasing chest compressions, they may also cause other effects, such as earlier refibrillation and more time spent in VF, with as yet unknown consequences.”

Interestingly the Cardio-pump was used in this study to provide chest compressions, which is an active compression-decompression device, potentially limiting the generalisability of the findings to manual compression-only CPR situations. Potential bias was also introduced by the exclusion of patients in whom consent from relatives was not obtained. Nevertheless it’s good to see such rigorous clinical research applied to this area.

DEFI 2005. A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Effect of Automated External Defibrillator Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Protocol on Outcome From Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

Circulation. 2010;121:1614-1622

Normal ECG still doesn't rule out PE

ECGs from a prospective study of patients in the ED with suspected pulmonary embolism were studied to identify the relative frequency of ECG features of pulmonary hypertension. For a patient to be eligible for enrollment, a physician was required to have sufficient suspicion for pulmonary embolism to order objective diagnostic testing in the ED. Such testing included D-dimer measurement, computed tomography pulmonary angiography, ventilation/perfusion scanning, or venous ultrasonography.

ECGs were done in 6049 patients, 354 (5.9%) of whom were diagnosed with pulmonary embolism. The frequency, positive likelihood ratio (LR+) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of each predictor were as follows:

- S1Q3T3 8.5% with pulmonary embolism versus 3.3% without pulmonary embolism (LR+ 3.7; 95% CI 2.5 to 5.4)

- nonsinus rhythm, 23.5% versus 16.6% (LR+ 1.4; 95% CI 1.2 to 1.7)

- inverted T waves in V1 to V2, 14.4% versus 8.1% (LR+ 1.8; 95% CI 1.3 to 2.3)

- inversion in V1 to V3, 10.5% versus 4.0% (LR+ 2.6; 95% CI 1.9 to 3.6)

- inversion in V1 to V4, 7.3% versus 2.0% (LR+ 3.7; 95% CI 2.4 to 5.5)

- incomplete right bundle branch block, 4.8% versus 2.8% (LR+ 1.7; 95% CI 1.0 to 2.7)

- tachycardia (pulse rate>100 beats/min), 28.8% versus 15.7% (LR+ 1.8; 95% CI 1.5 to 2.2).

The authors point out that the study may be subject to reporting bias or incorporation bias because those patients with ECG abnormalities may have then been more likely to undergo further evaluation for PE.

Overall, they summarise that the main findings were that the S1Q3T3 pattern and precordial T-wave inversions had the highest LR(+) values with lower-limit 95% CIs above unity, whether or not the patient had preexisting cardiopulmonary disease, but emphasise that the sensitivities of each of these findings were low, and clinicians should not decrease their suspicion for pulmonary embolism according to their absence.

Likelihood ratios and specificities were similar when patients with previous cardiopulmonary disease were excluded from analysis.

12-Lead ECG Findings of Pulmonary Hypertension Occur More Frequently in Emergency Department Patients With Pulmonary Embolism Than in Patients Without Pulmonary Embolism

Ann Emerg Med. 2010 Apr;55(4):331-5

Atypical chest pain renders AMI more likely

A prospective study of 796 ED patients with suspected cardiac chest pain assessed the value of individual historical and examination findings for diagnosing acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and the occurrence of adverse events (death, AMI or urgent revascularization) within 6 months. AMI was diagnosed in 148 (18.6%) of the 796 patients recruited.

The results may surprise some physicians:

Sweating observed by the ED physician was the strongest predictor of AMI (adjusted OR 5.18, 95% CI 3.02–8.86).

Reported vomiting was also a fairly strong predictor of AMI (adjusted OR 3.50, 1.81–6.77).

Pain located in the left anterior chest was found to be the strongest negative predictor of AMI (adjusted OR 0.25, 0.14–0.46).

Patients who described the pain as being the same as previous myocardial ischaemia were significantly less likely to be having AMI!

Following adjustment for age, sex and ECG changes, the following characteristics made AMI more likely (adjusted odds ratio, 95% confidence intervals):

- pain radiating to the right arm (2.23, 1.24-4.00)

- pain radiating to both arms (2.69, 1.36-5.36)

- vomiting reported (3.50, 1.81-6.77), central chest pain (3.29, 1.94-5.61)

- sweating observed by physician (5.18, 3.02-8.86)

Pain in the left anterior chest made AMI significantly less likely (0.25, 0.14-0.46)

The presence of rest pain (0.67, 0.41-1.10) or pain radiating to the left arm (1.36, 0.89-2.09) did not significantly alter the probability of AMI.

Compare these results with the American Heart Association guidelines which state that “chest or left arm pain or discomfort as the chief symptom reproducing prior documented angina” is associated with a high likelihood of ACS, or the European Society of Cardiology guidelines which state that “the typical clinical presentation of NSTE-ACS is retrosternal pressure or heaviness radiating to the left arm, neck or jaw”, which the authors of this study point out are statements made based on expert opinion for which references are not given.

The authors summarise with a powerful message: ‘Several ‘atypical’ symptoms actually render AMI more likely, whereas many ‘typical’ symptoms that are often considered to identify high-risk populations have no diagnostic value.’

The value of symptoms and signs in the emergent diagnosis of acute coronary syndromes

Resuscitation. 2010 Mar;81(3):281-6

A smaller dose of tPA in PE

A prospective open label randomised controlled trial from China compared two doses of r-tPA for massive or submassive PE. 50 mg / 2hr was as efficacious as 100 mg / 2hr but had fewer bleeding complications. Bleeding was much more common in patients under 65 kg, suggesting perhaps there should be dose per kg instead of a nice round number?

Efficacy and safety of low dose recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator for the treatment of acute pulmonary thromboembolism: a randomized, multicenter, controlled trial.

Chest. 2010 Feb;137(2):254-62