Monthly Archives: April 2010

Thoracic Aortic Disease Guidelines

Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients With Thoracic Aortic Disease have been published by a collaboration between a number of professional bodies including the American Heart Association.

Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients With Thoracic Aortic Disease

Circulation. 2010 Apr 6;121(13):e266-369 – free Full Text as PDF

HTML full text

Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy/Dysplasia

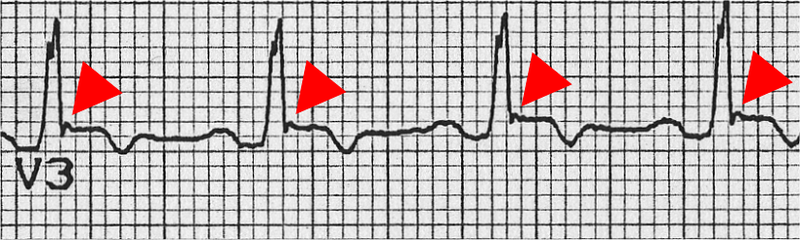

This disease may result in sudden cardiac death in young people, and the assessment of patients who present with dysrhythmias or syncope should prompt a review of the ECG for suggestive features of Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy/Dysplasia (as well as ischaemia, conduction deficits, WPW syndrome, Brugada syndrome, and prolonged QT interval).

A Task force has revised its diagnostic criteria for the disease, listed as major and minor criteria pertaining to family history, ECG, echo, MRI, and angiographic features. The ECG features that front line doctors need to be on the look out for include:

- Inverted T waves in right precordial leads (V1, V2, and V3) or beyond in individual >14 years of age (in the absence of complete right bundle-branch block QR>120 ms)

- Inverted T waves in leads V1 and V2 in individual>14 years of age (in the absence of complete right bundle-branch block) or in V4, V5, or V6

- Inverted T waves in leads V1, V2, V3, and V4 in individual>14 years of age in the presence of complete right bundle-branch block

- Epsilon wave (reproducible low-amplitude signals between end of QRS complex to onset of the T wave) in the right precordial leads (V1 to V3)

- Nonsustained or sustained ventricular tachycardia of left bundle-branch morphology with superior axis (negative or indeterminate QRS in leads II, III, and aVF and positive in lead aVL)

- Nonsustained or sustained ventricular tachycardia of RV outflow configuration, left bundle-branch block morphology with inferior axis (positive QRS in leads II, III, and aVF and negative in lead aVL) or of unknown axis

- >500 ventricular extrasystoles per 24 hours (Holter)

Diagnosis of Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy/Dysplasia Proposed Modification of the Task Force Criteria

Circulation. 2010 Apr 6;121(13):1533-41

More info on this disease from the European Society of Cardiology here

Crystalloids vs colloids and cardiac output

It is said that when using crystalloids, two to four times more fluid may be required to restore and maintain intravascular fluid volume compared with colloids, although true evidence is scarce. The ratio in the SAFE study comparing albumin with saline resuscitation was 1:1.3, however.

A single-centre, single- blinded, randomized clinical trial was carried out on 24 critically ill sepsis and 24 non-sepsis patients with clinical hypovolaemia, assigned to loading with normal saline, gelatin 4%, hydroxyethyl starch 6% or albumin 5% in a 90-min (delta) central venous pressure (CVP)-guided fluid loading protocol. Haemodynamic monitoring using transpulmonary thermodilution was done each 30 min to measure, among other things, global end-diastolic volume and cardiac indices (GEDVI, CI). The reason sepsis was looked at was because of a suggestion in the SAFE study of benefit from albumin in the pre-defined sepsis subgroup.

Independent of underlying disease, CVP and GEDVI increased more after colloid than saline loading (P = 0.018), so that CI increased by about 2% after saline and 12% after colloid loading (P = 0.029).

Their results agree with the traditional (pre-SAFE) idea of ratios of crystalloid:colloid, since the difference in cardiac output increase multiplied by the difference in volume infused was three for colloids versus saline.

Take home message? Even though an outcome benefit has not yet been conclusively demonstrated, colloids such as albumin increase pre-load and cardiac index more effectively than equivalent volumes of crystalloid in hypovolaemic critically ill patients.

Greater cardiac response of colloid than saline fluid loading in septic and non-septic critically ill patients with clinical hypovolaemia

Intensive Care Med. 2010 Apr;36(4):697-701

Magnesium for subarachnoid haemorrhage

Symptomatic cerebral vasospasm occurs in nearly one-third of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and is a major cause of disability and mortality in this population.

Magnesium (Mg) acts as a cerebral vasodilator by blocking the voltage-dependent calcium channels.. Experimental studies suggest that Mg also inhibits glutamate release by blocking N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, decreases intracellular calcium influx, and increases red blood cell deformability; all these changes may reduce the occurrence of cerebral vasospasm and minimise brain ischemic injury occurring after SAH.

One hundred and ten patients within 96 hours of admission for aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) were randomised to receive iv magnesium or placebo. Nimodipine was not routinely given. Twelve patients (22%) in the magnesium group and 27 patients (51%) in the control group had delayed ischemic infarction – the primary endpoint (p< .0020; odds ratio [OR], 0.28; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.12– 0.64). Mortality was lower and neurological outcome better in the magnesium group but these results were not statistically significant.

Larger trials of magnesium in SAH are ongoing.

Prophylactic intravenous magnesium sulfate for treatment of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical study

Crit Care Med. 2010 May;38(5):1284-90

Update September 2012:

A multicentre RCT showed intravenous magnesium sulphate does not improve clinical outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage, therefore routine administration of magnesium cannot be recommended.

Magnesium for aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (MASH-2): a randomised placebo-controlled trial

Lancet 2012 July 7; 380(9836): 44–49 Free full text

[EXPAND Click to read abstract]

Background Magnesium sulphate is a neuroprotective agent that might improve outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage by reducing the occurrence or improving the outcome of delayed cerebral ischaemia. We did a trial to test whether magnesium therapy improves outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Methods We did this phase 3 randomised, placebo-controlled trial in eight centres in Europe and South America. We randomly assigned (with computer-generated random numbers, with permuted blocks of four, stratified by centre) patients aged 18 years or older with an aneurysmal pattern of subarachnoid haemorrhage on brain imaging who were admitted to hospital within 4 days of haemorrhage, to receive intravenous magnesium sulphate, 64 mmol/day, or placebo. We excluded patients with renal failure or bodyweight lower than 50 kg. Patients, treating physicians, and investigators assessing outcomes and analysing data were masked to the allocation. The primary outcome was poor outcome—defined as a score of 4–5 on the modified Rankin Scale—3 months after subarachnoid haemorrhage, or death. We analysed results by intention to treat. We also updated a previous meta-analysis of trials of magnesium treatment for aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. This study is registered with controlled-trials.com (ISRCTN 68742385) and the EU Clinical Trials Register (EudraCT 2006-003523-36).

Findings 1204 patients were enrolled, one of whom had his treatment allocation lost. 606 patients were assigned to the magnesium group (two lost to follow-up), 597 to the placebo (one lost to follow-up). 158 patients (26·2%) had poor outcome in the magnesium group compared with 151 (25·3%) in the placebo group (risk ratio [RR] 1·03, 95% CI 0·85–1·25). Our updated meta-analysis of seven randomised trials involving 2047 patients shows that magnesium is not superior to placebo for reduction of poor outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (RR 0·96, 95% CI 0·86–1·08).

Interpretation Intravenous magnesium sulphate does not improve clinical outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage, therefore routine administration of magnesium cannot be recommended.

[/EXPAND]

Current Controversy in RSI

A review article in Anesthesia and Analgesia provides a summary of the literature surrounding RSI controversies.

- Should a pre-determined dose of induction drug be given or should it be titrated to effect prior to giving suxamethonium?

- Should fast acting opioids be coadministered to blunt the pressor response?

- What is the optimal dose of suxamethonium?

- Should defasciculating doses of neuromuscular blocking drugs be given?

- What is the ‘priming’ technique with rocuronium and is it necessary?

- Is it really bad to bag-mask ventilate the patient after induction prior to intubation? Which patients might this benefit?

- Should patients with full stomachs be anaesthetised sitting up, supine, or head down?

- Is cricoid pressure a good or a bad thing?

Not surprisingly the jury is still out on these, which is of course why they remain ‘controversies’. The review article provides a readable, interesting, and up to date summary of the evidence to date.

Rapid Sequence Induction and Intubation: Current Controversy

Anesth Analg. 2010 May 110(5):1318-25

Inhaled NPA

A case is reported of a stroke patient who aspirated his nasopharyngeal airway, resulting in coughing and desaturation. After iv propofol and topical anaesthesia to the oropharynx and hypopharynx, it was seen on laryngoscopy to be within the trachea but could not be retrieved with Magill forceps. Instead, his doctors inserted a well lubricated 14 Fr foley catheter through the lumen of the tube, inflated the balloon, and pulled it out.

Retrieval of Aspirated Nasopharyngeal Airway Using Foley Catheter

Anesth Analg. 2010 Apr;110(4):1245-6

A close look at the Sun

NASA’s recently launched Solar Dynamics Observatory, or SDO, is returning early images that confirm an unprecedented new capability for scientists to better understand our sun’s dynamic processes. These solar activities affect everything on Earth.

Some of the images from the spacecraft show never-before-seen detail of material streaming outward and away from sunspots. Others show extreme close-ups of activity on the sun’s surface. The spacecraft also has made the first high-resolution measurements of solar flares in a broad range of extreme ultraviolet wavelengths.

“These initial images show a dynamic sun that I had never seen in more than 40 years of solar research,” said Richard Fisher, director of the Heliophysics Division at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “SDO will change our understanding of the sun and its processes, which affect our lives and society. This mission will have a huge impact on science, similar to the impact of the Hubble Space Telescope on modern astrophysics.”

Launched on Feb. 11, 2010, SDO will provide images with clarity 10 times better than high-definition television. SDO will send 1.5 terabytes of data back to Earth each day, which is equivalent to a daily download of half a million songs onto an MP3 player.

The SDO “is shedding new light on our closest star, the sun, discovering new information about powerful solar flares that affect us here on Earth by damaging communication satellites and temporarily knocking out power grids. Better data means more accurate solar storm warnings.”

More information from NASA

Scalp veins

While clearing up after teaching with my bald colleague Dr Phil Hyde yesterday I noticed his bulging scalp veins and this reminded me that we don’t talk about this route much in our Paediatric Emergency Medicine Course.

This prompted me to look up the complications of scalp vein access in neonates and infants, which include:

- scalp abscess

- alopecia

- intracranial abscess

- thrombophlebitis

- intracranial venous sinus air embolism

- scalp necrotising fasciitis

Suggested ways to decrease the risk of complications include:

- A vein should not be used for more than 24 h at a time

- The needle entry point should not be covered

- The butterfly needle should be immobilized to avoid movements of the needle into the tissue with consequent extravasation of fluid

- The infusion site should be monitored by regular examination

- If a swelling or leakage of fluid is noted, the infusion should be discontinued immediately from that site

- The hair should be properly shaved

- If the line is required for more than 24 h, a peripheral venous cutdown or central venous line should be considered, after initial resuscitation

- An alternative route for rehydration (e.g. intraosseous infusion) should be considered initially, rather than risk multiple, unsuccessful attempts at scalp vein cannulation.

Complications of scalp vein infusion in infants

Trop Doct. 2005 Jan;35(1):46-7

Air emboli in the intracranial venous sinuses of neonates

Am J Perinatol. 2002 Jan;19(1):55-8

European Trauma Bleeding Guidelines updated

Update 2013: since this post was written in 2010, new guidelines have been written entitled: “Management of bleeding and coagulopathy following major trauma: an updated European guideline” which are available here

The 2007 guidelines on management of bleeding in trauma have been updated in the light of new evidence and modern practice. The guideline group summarises their recommendations as:

- We recommend that the time elapsed between injury and operation be minimised for patients in need of urgent surgical bleeding control. (Grade 1A).

- We recommend adjunct tourniquet use to stop life-threatening bleeding from open extremity injuries in the pre-surgical setting. (Grade 1C).

- We recommend that the physician clinically assess the extent of traumatic haemorrhage using a combination of mechanism of injury, patient physiology, anatomical injury pattern and the patient’s response to initial resuscitation. (Grade 1C).

- We recommend initial normoventilation of trauma patients if there are no signs of imminent cerebral herniation. (Grade 1C).

- We recommend that patients presenting with haemorrhagic shock and an identified source of bleeding undergo an immediate bleeding control procedure unless initial resuscitation measures are successful. (Grade 1B).

- We recommend that patients presenting with haemorrhagic shock and an unidentified source of bleeding undergo immediate further investigation. (Grade 1B).

- We recommend early imaging (FAST or CT) for the detection of free fluid in patients with suspected torso trauma. (Grade 1B).

- We recommend that patients with significant free intraabdominal fluid and haemodynamic instability undergo urgent intervention. (Grade 1A).

- We recommend further assessment using computed tomography for haemodynamically stable patients who are either suspected of having torso bleeding or have a high risk mechanism of injury. (Grade 1B).

- We do not recommend the use of single haematocrit measurements as an isolated laboratory marker for bleeding. (Grade 1B).

- We recommend both serum lactate and base deficit measurements as sensitive tests to estimate and monitor the extent of bleeding and shock. (Grade 1B).

- We recommend that routine practice to detect post-traumatic coagulopathy include the measurement of international normalised ratio (INR), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), fibrinogen and platelets. INR and APTT alone should not be used to guide haemostatic therapy. (Grade 1C) We suggest that thrombelastometry also be performed to assist in characterising the coagulopathy and in guiding haemostatic therapy. (Grade 2C).

- We recommend that patients with pelvic ring disruption in haemorrhagic shock undergo immediate pelvic ring closure and stabilisation. (Grade 1B).

- We recommend that patients with ongoing haemodynamic instability despite adequate pelvic ring stabilisation receive early preperitoneal packing, angiographic embolisation and/or surgical bleeding control. (Grade 1B).

- We recommend that early bleeding control of the abdomen be achieved using packing, direct surgical bleeding control and the use of local haemostatic procedures. In the exsanguinating patient, aortic cross-clamping may be employed as an adjunct. (Grade 1C).

- We recommend that damage control surgery be employed in the severely injured patient presenting with deep hemorrhagic shock, signs of ongoing bleeding and coagulopathy. Additional factors that should trigger a damage control approach are hypothermia, acidosis, inaccessible major anatomic injury, a need for time-consuming procedures or concomitant major injury outside the abdomen. (Grade 1C).

- We recommend the use of topical haemostatic agents in combination with other surgical measures or with packing for venous or moderate arterial bleeding associated with parenchymal injuries. (Grade 1B).

- We recommend a target systolic blood pressure of 80-100 mmHg until major bleeding has been stopped in the initial phase following trauma without brain injury. (Grade 1C).

- We recommend that crystalloids be applied initially to treat the bleeding trauma patient. (Grade 1B) We suggest that hypertonic solutions also be considered during initial treatment. (Grade 2B) We suggest that the addition of colloids be considered within the prescribed limits for each solution in haemodynamically unstable patients. (Grade 2C).

- We recommend early application of measures to reduce heat loss and warm the hypothermic patient in order to achieve and maintain normothermia. (Grade 1C).

- We recommend a target haemoglobin (Hb) of 7-9 g/dl. (Grade 1C).

- We recommend that monitoring and measures to support coagulation be initiated as early as possible. (Grade 1C).

- We recommend that ionised calcium levels be monitored during massive transfusion. (Grade 1C) We suggest that calcium chloride be administered during massive transfusion if ionised calcium levels are low or electrocardiographic changes suggest hypocalcaemia. (Grade 2C).

- We recommend early treatment with thawed fresh frozen plasma in patients with massive bleeding. (Grade 1B) The initial recommended dose is 10-15 ml/kg. Further doses will depend on coagulation monitoring and the amount of other blood products administered. (Grade 1C).

- We recommend that platelets be administered to maintain a platelet count above 50 × 109/l. (Grade 1C) We suggest maintenance of a platelet count above 100 × 109/l in patients with multiple trauma who are severely bleeding or have traumatic brain injury. (Grade 2C) We suggest an initial dose of 4-8 platelet concentrates or one aphaeresis pack. (Grade 2C).

- We recommend treatment with fibrinogen concentrate or cryoprecipitate if significant bleeding is accompanied by thrombelastometric signs of a functional fibrinogen deficit or a plasma fibrinogen level of less than 1.5-2.0 g/l. (Grade 1C) We suggest an initial fibrinogen concentrate dose of 3- 4 g or 50 mg/kg of cryoprecipitate, which is approximately equivalent to 15-20 units in a 70 kg adult. Repeat doses may be guided by thrombelastometric monitoring and laboratory assessment of fibrinogen levels. (Grade 2C).

- We suggest that antifibrinolytic agents be considered in the bleeding trauma patient. (Grade 2C) We recommend monitoring of fibrinolysis in all patients and administration of antifibrinolytic agents in patients with established hyperfibrinolysis. (Grade 1B) Suggested dosages are tranexamic acid 10-15 mg/kg followed by an infusion of 1-5 mg/kg per hour or ε-aminocaproic acid 100-150 mg/kg followed by 15 mg/kg/h. Antifibrinolytic therapy should be guided by thrombelastometric monitoring if possible and stopped once bleeding has been adequately controlled. (Grade 2C).

- We suggest that the use of recombinant recombinant activated coagulation factor VII (rFVIIa) be considered if major bleeding in blunt trauma persists despite standard attempts to control bleeding and best-practice use of blood components. (Grade 2C).

- We recommend the use of prothrombin complex concentrate for the emergency reversal of vitamin K-dependent oral anticoagulants. (Grade 1B).

- We do not suggest that desmopressin (DDAVP) be used routinely in the bleeding trauma patient. (Grade 2C) We suggest that desmopressin be considered in refractory microvascular bleeding if the patient has been treated with platelet-inhibiting drugs such as aspirin. (Grade 2C).

- We do not recommend the use of antithrombin concentrates in the treatment of the bleeding trauma patient. (Grade 1C).

Management of bleeding following major trauma: an updated European guideline.

Crit Care. 2010 Apr 6;14(2):R52 (Pub Med abstract)

Full Text Link