An engaging scene from ‘Code Blue‘ demonstrated a Helicopter Emergency Medical Service team managing a patient with major thoracic haemorrhage. They did a right thoracotomy and wanted to clamp the hilum but there was some kit missing from the pack.

Unfortunately, the video is no longer available.

This scene had some great discussion points for prehospital professionals, even if the specific scenario is somewhat unlikely for most people’s practice:

- Non-compressible haemorrhage is possibly the biggest single clinical challenge when you’re a long way from hospital

- Agitated friends and family can be disruptive – allocate a rescuer to look after them

- Having blood products to give is essential

- Don’t rely on the memory of individuals, who are fallible, to pack your equipment. “I was sure I put them in” didn’t cut it when the team needed forceps to clamp the pulmonary hilum and stop the bleeding. Checklists are the in thing, for good reason.

- Luckily, you don’t need to clamp the hilum (which is tricky) in massive unilateral thoracic haemorrhage. You can just twist the lung 180 degrees on the hilum so it’s upside down. This can prevent further haemorrhage and air embolism.

What’s a hilar twist then?

The hilar twist manoeuvre, as it’s called, is worth learning if you’re a clinician who is prepared to do resuscitative clamshell thoracotomy for penetrating traumatic cardiac arrest. The clamshell is quick and provides excellent exposure(1) and is preferred to lateral thoracotomy(2).

The primary purpose of clamshell thoracotomy in penetrating traumatic arrest is to relieve cardiac tamponade and control a cardiac wound(3). It is well described and continues to save lives in the prehospital setting(4).

However, sometimes you’ll open the chest and the pericardium will be empty (other than containing the heart of course), and there will be massive haemorrhage on one side of the chest. Although most of these patients will be unsalvageable outside a trauma centre’s operating room, it’s worth trying something once you’ve gone to all the trouble of opening the chest. The hilar twist(5) is probably the best option for the non-surgeon, especially when some muppet’s forgotten to pack a clamp.

In order to make the lung mobile enough to twist, it’s first necessary to cut through the inferior pulmonary ligament. This is also known as simply the pulmonary ligament (because there’s no superior equivalent) and sometimes the inferior hilar ligament. It’s not actually a ligament, but an extension of the parietal pleura extending downwards in a fold from the hilum. Some describe it as hanging down from the hilum like a ‘wizard’s sleeve’, which invariably gets a giggle from some of our trainees from the United Kingdom for some reason.

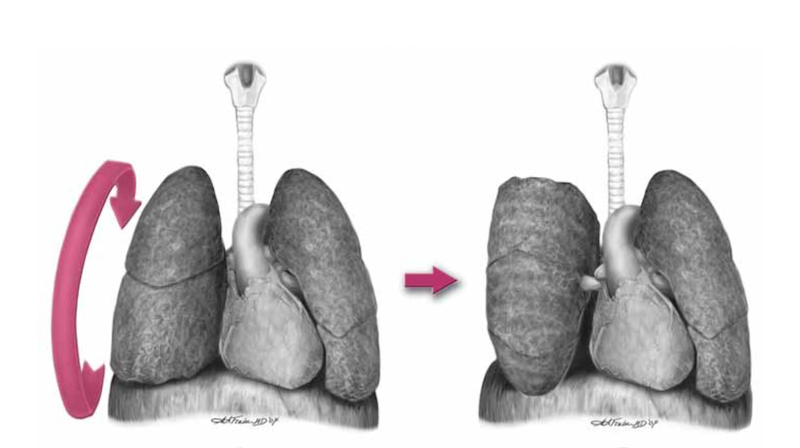

After cutting the ligament completely to the level of the inferior pulmonary vein, the lung is then twisted ‘lower lobe towards you’, ie. lower lobe is rotated anteriorly over the upper lobe until the lung is oriented ‘upside down’. The twisted vessels around the hilum become occluded and further haemorrhage from that side should be limited. Other priorities in the arrested patient will be aortic occlusion, internal cardiac massage, and blood products. Packs may be required to keep the lung from untwisting, and if return of spontaneous circulation is achieved, there is a risk of dysrhythmia, right heart failure, and refractory hypoxaemia.

I’ve only done this on pigs and human cadavers so am not speaking from any reassuring level of experience or competence. The literature is out there to read, and it’s up to you to decide how you want to expand or limit your options when you’ve cracked that chest in an arrested patient.

References

1. Flaris AN, Simms ER, Prat N, Reynard F, Caillot J-L, Voiglio EJ. Clamshell incision versus left anterolateral thoracotomy. Which one is faster when performing a resuscitative thoracotomy? The tortoise and the hare revisited. World J Surg. 2015 May;39(5):1306–11.

2. Simms ER, Flaris AN, Franchino X, Thomas MS, Caillot J-L, Voiglio EJ. Bilateral Anterior Thoracotomy (Clamshell Incision) Is the Ideal Emergency Thoracotomy Incision: An Anatomic Study. World J Surg. 2013 Feb 23;37(6):1277–85.

3. Wise D. Emergency thoracotomy: “how to do it.” Emerg Med J. 2005 Jan 1;22(1):22–4.

4. Davies GE, Lockey DJ. Thirteen Survivors of Prehospital Thoracotomy for Penetrating Trauma: A Prehospital Physician-Performed Resuscitation Procedure That Can Yield Good Results. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 2011 May;70(5):E75–8.

5. Wilson A, Wall MJ Jr., Maxson R, Mattox K. The pulmonary hilum twist as a thoracic damage control procedure. The American Journal of Surgery. 2003 Jul;186(1):49–52.