An abstract from the The National Association of EMS Physicians® 2010 Scientific Assembly published in a Supplement of Prehospital Emergency Care describes a study comparing cadaveric intubation success rates by paramedics in different positions: on the floor, on an elevated stretcher, and in a simulated ambulance. Despite less experience intubating on an elevated stretcher, the participants had increased first-attempt success in the elevated stretcher position compared with the back of the ambulance and the floor (although in the latter case this lacked statistical significance). Position is everything! In our HEMS service we prefer a lowered stretcher to either on the ground or in the ambulance – it would be nice to see this position studied one day too.

Pre-hospital intubation: patient position does matter

Prehospital Emergency Care 2010;14(Suppl 1):9

Tag Archives: airway

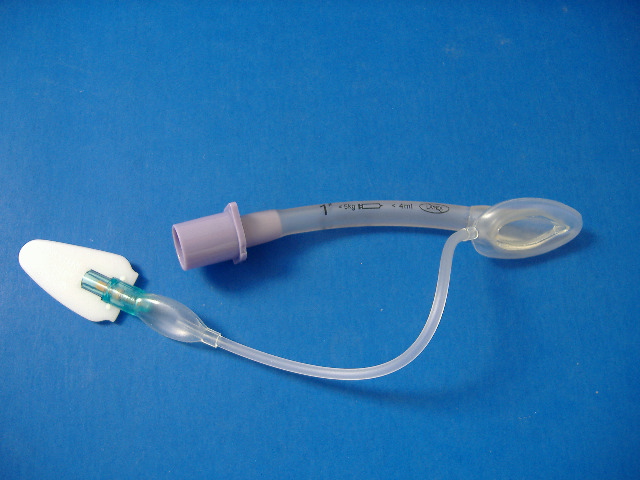

LMA for newborn resuscitation

An observational study of near term infants (34 weeks gestation to 36 weeks and 6 days) born in an Italian centre over a 5 year period showed that nearly 10% of near-term infants needed positive pressure ventilation at birth, confirming that this group of patients is more vulnerable than term infants. Most were able to be managed with either bag-mask ventilation (BMV) or with a size 1 laryngeal mask airway (LMA). Of the 86 infants requiring PPV, 36 (41.8%) were managed by LMA, 34 (39.5%) by BMV and 16 (18.6%) by tracheal intubation. Why not slap a tiny LMA on your neonatal resuscitation cart – it could come in handy!

Delivery room resuscitation of near-term infants: role of the laryngeal mask airway

Resuscitation. 2010 Mar;81(3):327-30

Do all comatose patients need intubation?

In non-trauma patients, do you base your decision to intubate patients with decreased conscious level on the GCS? These guys in Scotland describe a series of poisoned patients with GCS range 3-14 managed on an ED observation unit without tracheal intubation, with no demonstrated cases of aspiration. They say: ‘This study suggests that it can be safe to observe poisoned patients with decreased consciousness, even if they have a GCS of 8 or less, in the ED‘. Small numbers, but gets you thinking. This subject would make a great randomised controlled trial.

Decreased Glasgow Coma Scale score does not mandate endotracheal intubation in the emergency department

J Emerg Med. 2009 Nov;37(4):451-5

Bad news for etomidate from CORTICUS

In an a priori substudy of the CORTICUS multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of hydrocortisone in septic shock, the use and timing of etomidate administration was examined in relation to outcome.

Of 499 analysable patients, 96 (19.2%) received etomidate within the 72 h prior to inclusion. The proportion of non-responders to ACTH was significantly higher in patients who were given etomidate than in other patients (61.0 vs. 44.6%, P = 0.004). Etomidate therapy was associated with a higher 28-day mortality in univariate analysis (P = 0.02) and after correction for severity of illness (42.7 vs. 30.5%; P=0.06 and P=0.03) in two multi-variant models. Hydrocortisone administration did not change the mortality of patients receiving etomidate (45 vs. 40%).

Some of the previous attacks on etomidate have not been founded on the most rigorous evidence. However this study adds further to the difficulty in justifying etomidate’s use when a perfectly acceptable alternative (ketamine) exists for rapid sequence induction in the haemodynamically unstable septic patient.

The effects of etomidate on adrenal responsiveness and mortality in patients with septic shock.

Intensive Care Med. 2009 Nov;35(11):1868-76

Difficult mask ventilation

A comprehensive review of difficult mask ventilation (DMV) reports that the incidence of DMV varies widely (from 0.08% to 15%) depending on the criteria used for its definition. It reminds us that the independent predictors of DMV are:

- Obesity

- Age older than 55 yr

- History of snoring

- Lack of teeth

- The presence of a beard

- Mallampati Class III or IV

- Abnormal mandibular protrusion test

The review also points out that DMV does not automatically mean difficult laryngoscopy, although it does increase its likelihood.

In addition to positioning, oral and nasal adjuncts, two person technique, and jaw thrust, the application of 10 cmH20 CPAP may help splint open the airway and reduce the difficulty of mask ventilation in some patients.

Difficult mask ventilation

Anesth Analg. 2009 Dec;109(6):1870-80

Causes of DMV:

1) Technique-related

1. Operator: Lack of experience

2. Equipment

a. Improper mask size

b. Difficult mask fit: e.g., beard, facial anomalies, retrognathia

c. Leakage from the circuit

d. Faulty valve

e. Improper oral/nasal airway size

3. Position: Suboptimal head and neck position

4. Incorrectly applied cricoid pressure

5. Drug related

a. Opioid-induced vocal cord closure

b. Succinylcholine-induced masseter rigidity

c. Inadequate depth of anesthesia

d. Lack of relaxation?

2) Airway-related

1. Upper airway obstruction

a. Tongue or epiglottis

b. Redundant soft tissue in morbid obesity and sleep

apnea patients

c. Tonsillar hyperplasia

d. Oral, maxillary, pharyngeal, or laryngeal tumor

e. Airway edema e.g., repeated intubation attempts,

trauma, angioedema

f. Laryngeal spasm

g. External compression e.g., large neck masses and

neck hematoma

2. Lower airway obstruction

a. Severe bronchospasm

b. Tracheal or bronchial tumor

c. Anterior mediastinal mass

d. Stiff lung

e. Foreign body

f. Pneumothorax

g. Bronchopleural fistula

3) Severe chest wall deformity or kyphoscoliosis restricting chest expansion

Cricoid pressure squashes kids' airways

A bronchoscopic study of anaesthetised infants and children receiving cricoid pressure revealed the procedure to distort the airway or occlude it by more than 50% with as little as 5N of force in under 1s and between 15 and 25N in teenagers. Therefore forces well below the recommended value of 30 N will cause significant compression/distortion of the airway in a child

Effect of cricoid force on airway calibre in children: a bronchoscopic assessment

Br J Anaesth. 2010 Jan;104(1):71-4

A novel jaw thrust device

A novel jaw thrust device (JTD) was tested against oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal airways in anaesthetised patients. The JTD enabled effective ventilation with less airway resistance than the traditional airways, and so provided greater tidal volumes during pressure controlled ventilation. It fits into the mouth, keeping the mouth open and the jaw thrusted forward, and has a standard sized connector for attachment to ventilation devices.

Optimising the unprotected airway with a prototype Jaw-Thrust-Device – a prospective randomised cross-over study

Anaesthesia. 2009 Nov;64(11):1236-40

Securing infant tracheal tubes

Small head movements can cause significant tracheal tube migration in infants unless the tube is adequately secured.

Many use a version of the Melbourne strapping method:

1. Equipment required: Silk suture (cut off needle), ‘Cavilon’, elastoplast cut into 3 strips – 2 trouser shaped, and one with a 4cm hole in middle.

2. Apply Cavilon to face (a barrier film to protect the skin) over the area shown by red blobs in the picture.

3. Tie the suture around the tracheal tube. This marks the tube position at the mouth, and allows the tube to be held in place during fixation and when the tapes are later changed.

Pull the two ends taut across both cheeks.

3. While the suture is being pulled taut, place the first ‘trousers’ so that the undivided end is along the cheek (over the tape). The lower ‘leg’ is placed between the lower lip and the chin.

The upper ‘leg’ is folded back on itself to make it easier to removed at a later stage. It is then wound around the tracheal tube

4. The second set of ‘trousers’ is then applied on the other side, once again with the undivided end over the cheek and suture.

The upper ‘leg’ goes between the nose and the top lip and the lower leg is wound around the tracheal tube.

5. Finally the third piece of elastoplast is placed so that the tube goes through the hole

and applied over the other tapes. If there is an orogastric tube this should also go through the hole. The tube is now secure for transfer.

Standards for Capnography in Critical Care

The Intensive Care Society has published guidelines on the use of capnography in critical care. The recommendations are:

- Capnography should be used for all critically ill patients during the procedures of tracheostomy or endotracheal intubation when performed in the intensive care unit.

- Capnography should be used in all critically ill patients who require mechanical ventilation during inter-hospital or intra- hospital transfer.

- Rare situations in which capnography is misleading can be reduced by increasing staff familiarity with the equipment, and by the use of bronchoscopy to confirm tube placement where the tube may be displaced but remains in the respiratory tract.

Other findings:

- Capnography offers the potential for non-invasive measurement of additional physiological variables including physiological dead space and total CO2 production.

- Capnography is not a substitute for estimation of arterial CO2.

- Careful consideration should be given to the type of capnography that should be used in an ICU. The decision will be influenced by methods used for humidification, and the advantages of active or passive humidification should be reviewed.

- Capnometry is an alternative to capnography where capnography is not available, for example where endotracheal intubation is required in general ward areas.

HEMS paramedic intubation success

All medical out of hospital cardiac arrests attended by the Warwickshire and Northamptonshire Air Ambulance (WNAA) over a 64-month period were reviewed. There were no significant differences in self-reported intubation failure rate, morbidity or clinical outcome between doctor-led and paramedic-led cases. The authors conclude that experienced paramedics regularly operating with physicians have a low tracheal intubation failure rate at out of hospital cardiac arrests, whether practicing independently or as part of a doctor-led team, and that this is likely due to increased and regular clinical exposure.

Can experienced paramedics perform tracheal intubation at cardiac arrests? Five years experience of a regional air ambulance service in the UK

Resuscitation. 2009 Dec;80(12):1342-5