A recent paper reminds us that surgery is an option in the management of massive pulmonary embolism(1), to be considered in the patient for whom thrombolysis has failed or is contraindicated. Good outcomes were produced when surgery was performed in a centre capable of cardiopulmonary bypass (6% 30-day postoperative mortality), but is surgery an option when these facilities are unavailable?

The “venous inflow occlusion” technique involves clamping the venae cavae prior to removing clot directly from the pulmonary artery and its branches after median sternotomy, and can be performed in any hospital with surgical facilities. Under normothermic conditions, speed is of the essence once cardiac arrest occurs, since the irreversible anoxic cerebral injury will occur after just a few minutes.

Clarke and Abrams wrote in the Lancet in 1972(2):

Our use of venous inflow-occlusion has given results which compare well with those obtained with extracorporeal circulation. 50% of our patients survived. All patients who had emboli removed without an episode of ventricular asystole survived surgery. Late deaths in 3 patients were from causes unrelated to pulmonary embolism, and from a further massive pulmonary embolus a week later. The technique has been applied with equal success in a major hospital fully equipped for cardiac surgery and in hospitals where resident and nursing staff had no experience of either thoracic or cardiac surgery. The simplicity and speed of the method has enabled the obstructed right ventricle to be relieved within thirty minutes of the onset of symptoms. The interval between induction of anaesthesia and the skin incision should be kept as short as possible, and drugs to maintain the blood pressure should be given. The period between skin incision and the restoration of the circulation has, with practice, been reduced to ten minutes.

But this clearly still requires surgical expertise and facilities. Emergency physicians can open the chest to deal with penetrating trauma. Could an ED thoracotomy facilitate clot removal from the pulmonary artery?

In 1969, a lady in her 50s arrested on the ward after an operation to remove a mass via a left lateral thoractomy. Pulmonary embolism was suspected and her thoracotomy wound was re-opened and the pulmonary artery incised, resulting in the removal of large amounts of clot. Return of spontaneous circulation resulted after a brief period of internal cardiac massage. Her case was written up decades later, in 1998(3):

The patient recovered rapidly and left the hospital on the 21st day without signs of cerebral damage. This patient is now 86 years old, mentally normal, living alone, and doing her own housekeeping. She remembers the hospital stay and the past years as worth living

Some patients may be considered too high risk for surgery and in some centres Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) is an option. It has been used both as life support pending surgery(4), or as an alternative to surgery to allow heparinisation to be used(5,6).

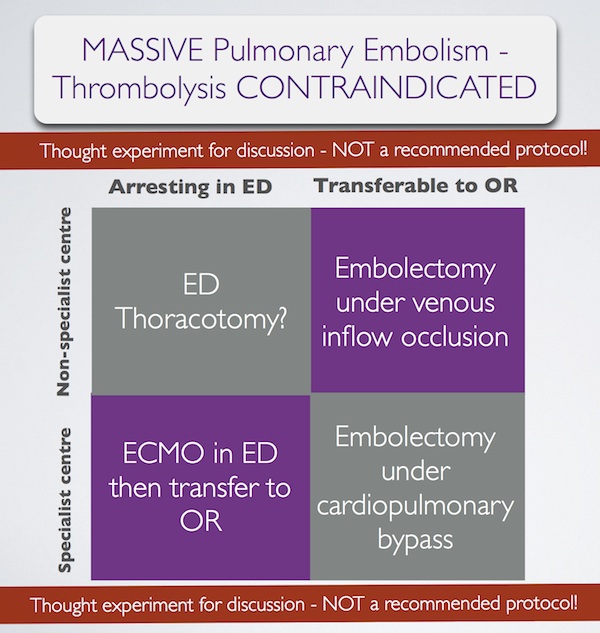

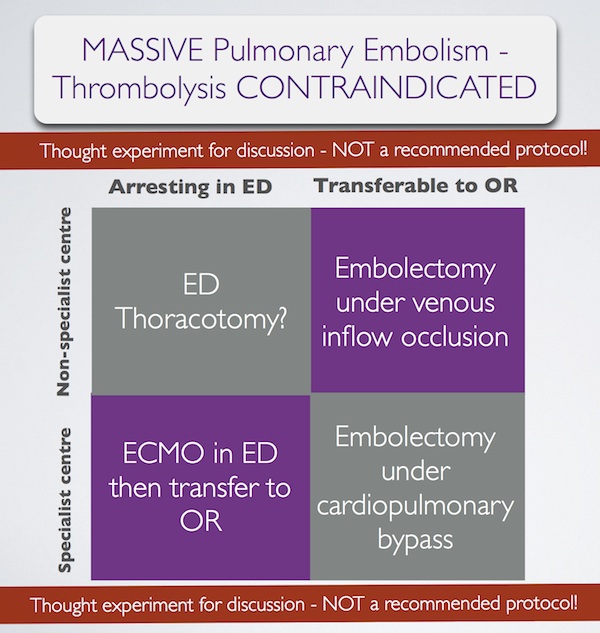

In summary, some patients with massive pulmonary embolism may benefit from surgery (contraindication to ‘lysis or failed ‘lysis). Getting them to surgery alive, or operating on them during cardiac arrest, is a challenge. Ideally they would undergo embolectomy under cardopulmonary bypass in the operating room, or could be placed on ECMO in the ED prior to going to the OR. If they present to a centre without these facilities, then the venous inflow occlusion technique could be used in the OR without bypass. Just rarely a patient may present in extremis with PE to an ED without these options. If that patient has major contraindications to thrombolysis, would an ED thoracotomy be something you would entertain?

I have done several thoracotomies for penetrating trauma but never for PE. I do not pretend to know how, and cannot find a case report of ED thoracotomy for pulmonary embolism in the literature. I’m therefore NOT recommending it. However, I would love to know people’s views on its feasibility. A possible approach could be summarised as:

Massive pulmonary embolism fascinates me, because it’s seen in the ‘talk and die’ patient. It is a single, treatable pathology that if diagnosed and treated appropriately truly makes the difference between life and death. When medicine presents us with an opportunity ‘on a plate’ like that to save a life, we need to be prepared. I have had great saves with this diagnosis and sadly have seen disastrous failures to act. When the time comes, we need to ask: ‘have we explored all options?’.

1. Surgical treatment of acute pulmonary embolism–a 12-year retrospective analysis.

Scand Cardiovasc J. 2012 Jun;46(3):172-6. Epub 2012 Mar 27.

OBJECTIVES: Surgical embolectomy for acute pulmonary embolism (PE) is considered to be a high risk procedure and therefore a last treatment option. We wanted to evaluate the procedures role in modern treatment of acute PE.

DESIGN: All data on patients treated with surgical embolectomy for acute PE were retrieved from our clinical database. The mortality was extracted from the Danish mortality register.

RESULTS: From October 1998 to July 2010, 33 patients underwent surgical embolectomy. All procedures were done through a median sternotomy and extracorporeal circulation. Twenty-six patients were diagnosed with a high risk PE and 7 with an intermediate risk PE and intracardial pathology. Six patients had been insufficiently treated with thrombolysis. Thirteen patients had contraindication for thrombolysis. Six patients were brought to the operating theatre in cardiogenic shock, 8 needed ventilator support, and 1 was in cardiac arrest. The postoperative 30-day mortality was 6% and during the 12-year follow-up the cumulative survival was 80% with 4 late deaths.

CONCLUSION: Surgical pulmonary embolectomy can be performed with low mortality although the treated patients belong to the most compromised part of the PE population. The results support surgical embolectomy as a vital part of the treatment algorithm for acute PE.

2. Pulmonary embolectomy with venous inflow-occlusion.

The Lancet 1972;1(7754):767–769

Massive pulmonary emboli have been removed surgically from 26 patients. The technique of normothermic circulatory arrest by venous inflow-occlusion was used in 25 patients. 13 patients survived. There were 10 operative deaths and 3 hospital deaths. Diagnosis was based upon clinical findings supplemented by electrocardiography and a plain radiograph of the chest. Surgery was offered to patients having a pulmonary embolus sufficiently massive to produce sustained hypotension. All patients whose hearts stopped beating before the embolectomy died. 6 successful operations were performed in hospitals without facilities for cardiac surgery. The method is recommended for its simplicity.

3. Left Anterior Thoracotomy for Pulmonary Embolectomy With 29-Year Follow-up

The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 1998, 66(4):1420-1421

Pulmonary embolectomy is usually performed in cardiopulmonary bypass. In acute situations too much time can be lost in setting up and connecting the pump oxygenator; this delay can cause cerebral damage in a patient with circulatory arrest. In such a situation left anterior thoracotomy can provide an ideal approach. An emergency thoracotomy can be performed in a few seconds. The lung automatically retracts. The phrenic nerve, pulmonary artery, and pericardium are clearly seen, and they outline the area for embolectomy. A case in which such an approach was successfully used is described.

4.ECMO treatment saved life of a young woman with acute pulmonary embolism

Lakartidningen 2004, 101(44):3420-3421

A 42-year old obese female using contraceptive medication was admitted to the emergency room because of sudden onset of dyspnoea and hypoxia. Computed tomography showed massive pulmonary emboli. Despite initial treatment with thrombolysis her condition deteriorated further and she was referred for acute surgery to our clinic. Before putting the patient to sleep extracorporeal circulation was instituted with access from the groin. After anaesthesia a median sternotomy was performed. With the heart beating, the main pulmonary artery was incised and a 9 cm long thrombus was removed. Immediate weaning from the heart-lung machine was not possible, mainly because of bleeding to the airways. The right atrium and the aorta was therefore cannulated and an extracorporeal circulation membrane oxygenator (ECMO) was used for three days. The patient required several re-entries for bleeding and a tracheotomy during the postoperative course. She was fully recovered three months after the operation.

5. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenator for pulmonary embolism.

The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 1997, 64(3):883-884 Free full text

6. Peripheral Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: Comprehensive Therapy for High-Risk Massive Pulmonary Embolism

Ann Thorac Surg 2012;94:104–8

Background: Although commonly reserved as a last line of defense, experienced centers have reported excellent results with pulmonary embolectomy for massive and submassive pulmonary embolism (PE). We present a contemporary surgical series for PE that demonstrates the utility of peripheral extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (pECMO) for high-risk surgical candidates.

Methods: Between June 2005 and April 2011, 29 patients were treated for massive or submassive pulmonary embolism, with surgical embolectomy performed in 26. Four high-risk patients were placed on pECMO, established by percutaneously cannulating the right atrium through a femoral vein and perfusing by a Dacron graft anastomosed to the axillary artery. A small, extracorporeal, rotary assist device was used, interposing a compact oxygenator in the circuit, and maintaining anticoagulation with heparin.

Results: Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was weaned in 3 of 4 patients after 5.3 days (5, 5, and 6), with normalization of right ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary artery pressure (44.0 ± 2.0 to 24.5 ± 5.5 mm Hg) by ECHO. Follow-up computed tomographies showed several peripheral, nearly resorbed emboli in 1 case and complete resolution in 2 others. The fourth patient, not improving after 10 days, underwent surgery where an embolic liposarcoma was extracted. For all 29 cases, hospital and 30-day mortality was 0% and all patients were discharged, with average postoperative length of stay of 15 days for embolectomy and 17 days for pECMO.

Conclusions: Heparin therapy with pECMO support is a rapid, effective option for patients who might benefit from pulmonary embolectomy but are at high risk for surgery.