Ever had to do a surgical airway in a child? Thought not. They’re pretty rare. Bill Heegaard MD from Henepin County Medical Center taught me a few approaches (with the help of an anaesthetised rabbit) which really got me thinking. It’s something I’d often trained for in my internal simulator, and I even keep the equipment for it in my house (listen out for an upcoming podcast on that). Research and experience has demonstrated that open surgical airway techniques are more reliable than transtracheal needle techniques in adults, but what about kids, in whom traditional teaching cautions against open techniques?

Australian investigators who were experienced airway proceduralists evaluated transtracheal needle techniques using a rabbit model (an excellent model for the infant airway). Their success rate was only 60% and they perforated the posterior tracheal wall in 42% of attempts. Of 13 attempts to insert a dedicated paediatric tracheotomy device, the Quicktrach Child, none were successful(1) (they did not use the Quicktrach Infant model as it is not available in Australia).

Danish investigators used fresh piglet cadavers weighing around 8 kg to assess two transtracheal cannulas, in which they achieved success rates of 65.6% and 68.8%(2). There was also a very high rate of posterior tracheal wall perforation. Using an open surgical tracheostomy technique, they were successful in 97% of attempts. These were also experienced operators, with a median anaesthetic experience of 12.5 years.

Their tracheotomy technique was nice and simple, and used just a scalpel, scissors, and surgical towel clips. Here’s their technique:

Simple tracheotomy procedure described by Holm-Knudsen et al

- Identify larynx and proximal trachea by palpation

- Vertical incision through the skin and subcutaneous tissue from the upper part of larynx to the sternal notch

- Grasp strap muscles with two towel forceps and separate in the midline

- Palpate and identify the trachea (palpate rather than look for tracheal rings, as in a live patient one would expect bleeding to obscure the view)

- Stabilise the trachea by grasping it with a towel forceps

- Insert sharp tip of the scissors between two tracheal rings and lift the trachea anteriorly to avoid damage to the posterior wall

- Cut vertically in the midline of the trachea with the scissors – they chose to use the scissors to cut the tracheal rings to facilitate tube insertion

- Insert the tracheal tube

Using ultrasound and CT to evaluate comparative airway dimensions, the authors concluded that the pig model is most useful for training emergency airway management in older children aged 5–10 years.

Why were they doing a tracheotomy rather than a cricothyroidotomy? Reasons given by the authors include:

- The infant cricothyroid membrane is very small

- Palpation of the thyroid notch may be hindered by the overlying hyoid bone

- The mandible may obstruct needle access to the cricothyroid membrane given the cephalad position in the neck of the infant larynx.

From an emergency medicine point of view, there are a couple of other reasons why we need to be able to access the trachea lower than the cricothyroid membrane. One is fractured larynx or other blunt or penetrating airway injury where there may be anatomical disruption at the cricothyroid level. The other situation is foreign body airway obstruction, when objects may lodge at the level of the cricoid ring which is functionally the narrowest part of the pediatric upper airway. Of course, alternative methods might be considered to remove the foreign body prior to tracheotomy, such as employing basic choking algorithms, and other techniques depending on whether you do or don’t have equipment.

Take home messages

- Transtracheal airways in kids are so rare, we can’t avoid extrapolating animal data

- Whichever infant or paediatric model is used, transtracheal needle techniques have a high rate of failure even by ‘experienced’ operators

- The small size and easy compressibility of the airway probably contributes to this failure rate, including the high rate of posterior wall puncture

- In keeping with adult audit data, open surgical techniques may have a higher success rate

- Tracheotomy may be necessary rather than cricothyroidotomy in infants and children depending on clinical scenario and accessibility of anatomy

- The stress and blood that is not simulated in cadaveric animal models will make open tracheotomy harder in a live patient, and so these success rates may not translate. However these factors do mean that whatever technique is used must be kept simple and should employ readily available and familiar equipment

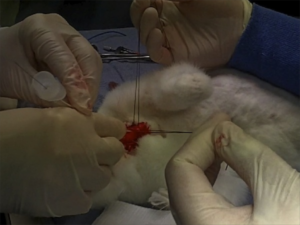

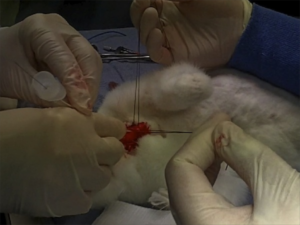

- Something to maintain control and anterior position of the anterior trachea wall should be used during incision and intubation of the trachea. The study reported here used towel clips; sutures around the tracheal rings may also be used (see image below)

I recommend you add ‘paediatric tracheotomy’ to the list of procedures you might need to do (if it’s not already there). Identify what equipment you would use and run the simulation in your head and in your work environment.

Have fun.

1. The ‘Can’t Intubate Can’t Oxygenate’ scenario in Pediatric Anesthesia: a comparison of different devices for needle cricothyroidotomy

Paediatr Anaesth. 2012 Dec;22(12):1155-8

BACKGROUND: Little evidence exists to guide the management of the ‘Can’t Intubate, Can’t Oxygenate’ (CICO) scenario in pediatric anesthesia.

OBJECTIVES: To compare two intravenous cannulae for ease of use, success rate and complication rate in needle tracheotomy in a postmortem animal model of the infant airway, and trial a commercially available device using the same model.

METHODS: Two experienced proceduralists repeatedly attempted cannula tracheotomy in five postmortem rabbits, alternately using 18-gauge (18G) and 14-gauge (14G) BD Insyte(™) cannulae (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Attempts began at the first tracheal cartilage, with subsequent attempts progressively more caudad. Success was defined as intratracheal cannula placement. In each rabbit, an attempt was then made by each proceduralist to perform a cannula tracheotomy using the Quicktrach Child(™) device (VBM Medizintechnik GmbH, Sulz am Neckar, Germany).

RESULTS: The rabbit tracheas were of similar dimensions to a human infant. 60 attempts were made at cannula tracheotomy, yielding a 60% success rate. There was no significant difference in success rate, ease of use, or complication rate between cannulae of different gauge. Successful aspiration was highly predictive (positive predictive value 97%) and both sensitive (89%) and specific (96%) for tracheal cannulation. The posterior tracheal wall was perforated in 42% of tracheal punctures. None of 13 attempts using the Quicktrach Child(™) were successful.

CONCLUSION: Cannula tracheotomy in a model comparable to the infant airway is difficult and not without complication. Cannulae of 14- and 18-gauge appear to offer similar performance. Successful aspiration is the key predictor of appropriate cannula placement. The Quicktrach Child was not used successfully in this model. Further work is required to compare possible management strategies for the CICO scenario

2. Emergency airway access in children – transtracheal cannulas and tracheotomy assessed in a porcine model

Paediatr Anaesth. 2012 Dec;22(12):1159-65

OBJECTIVES: In the rare scenario when it is impossible to oxygenate or intubate a child, no evidence exists on what strategy to follow.

AIM: The aim of this study was to compare the time and success rate when using two different transtracheal needle techniques and also to measure the success rate and time when performing an emergency tracheotomy in a piglet cadaver model.

METHODS: In this randomized cross-over study, we included 32 anesthesiologists who each inserted two transtracheal cannulas (TTC) using a jet ventilation catheter and an intravenous catheter in a piglet model. Second, they performed an emergency tracheotomy. A maximum of 2 and 4 min were allowed for the procedures, respectively. The TTC procedures were recorded using a video scope.

RESULTS: Placement of a transtracheal cannula was successful in 65.6% and 68.8% of the attempts (P = 0.76), and the median duration of the attempts was 69 and 42 s (P = 0.32), using the jet ventilation catheter and the intravenous catheter, respectively. Complications were frequent in both groups, especially perforation of the posterior tracheal wall. Performing an emergency tracheotomy was successful in 97%, in a median of 88 s.

CONCLUSIONS: In a piglet model, we found no significant difference in success rates or time to insert a jet ventilation cannula or an intravenous catheter transtracheally, but the incidence of complications was high. In the same model, we found a 97% success rate for performing an emergency tracheotomy within 4 min with a low rate of complications.