A study of out-of-hospital paediatric arrests in Melbourne gives some useful outcome data: overall, paediatric victims of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survived to leave hospital in 7.7% of cases, which is similar to adult survival in the same emergency system (8%). Survival was very rare (<1%) unless there was return of spontaneous circulation prior to hospital arrival. Sixteen of the 193 cases studied had trauma, but the survival in this subgroup was not specifically documented.

Epidemiology of paediatric out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Melbourne, Australia

Resuscitation. 2010 Sep;81(9):1095-100

Category Archives: Resus

Life-saving medicine

Ketamine for HEMS intubation in Canada

Ketamine was used by clinical staff from the The Shock Trauma Air Rescue Society (STARS) in Alberta to facilitate intubation in both the pre-hospital & in-hospital setting (with a neuromuscular blocker in only three quarters of cases). Changes in vital signs were small despite the severity of illness in the study population.

A prospective review of the use of ketamine to facilitate endotracheal intubation in the helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS) setting

Emerg Med J. 2010 Oct 6. [Epub ahead of print]

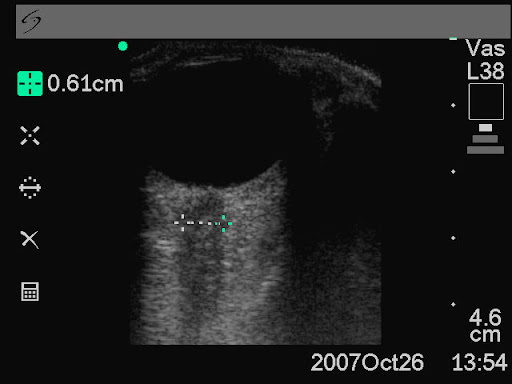

Ultrasound measurement of optic nerve sheath diameter

Here’s the abstract from a new study contributing the literature on ED assessment of raised intracranial pressure using ocular ultrasound:

Background To assess if ultrasound measurement of the optic nerve sheath diameter (ONSD) can accurately predict the presence of raised intracranial pressure (ICP) and acute pathology in patients in the emergency department.

Methods This 3-month prospective observational study used ultrasound to measure the ONSD in adult patients who required CT from the emergency department. The mean ONSD from both eyes was measured using a 7.5 MHz ultrasound probe on closed eyelids. A mean ONSD value of >0.5 cm was taken as positive. Two radiologists independently assessed CT scans from patients in the study population for signs of raised ICP and signs of acute pathology (cerebrovascular accident, subarachnoid, subdural or extradural haemorrhage and tumour). Specificity, sensitivity and k values, for interobserver variability between reporting radiologists, were generated for the study data.

Results In all, 26 patients were enrolled into the study. The ONSD measurement was 100% specific (95% CI 79% to 100%) and 86% sensitive (95% CI 42% to 99%) for raised ICP. For any acute intracranial abnormality the value of ONSD was 100% specific (95% CI 76% to 100%) and 60% sensitive (95% CI 27% to 86%). k Values were 0.91 (95% CIs 0.73 to 1) for identification of raised ICP on CT and 0.84 (95% CIs 0.62 to 1) for any acute pathology on CT, between the radiologists.

Conclusions This study shows that ultrasound measurement of ONSD is sensitive and specific for raised ICP in the emergency department. Further observational studies are needed but this emerging technique could be used to focus treatment in unstable patients.

Ultrasound measurement of optic nerve sheath diameter in patients with a clinical suspicion of raised intracranial pressure

Emerg Med J. 2010 Aug 15. [Epub ahead of print]

Cirrhotic patients on ICU

The prognosis of cirrhotic patients with multiple organ failure is not universally dismal. A retrospective French study examined predictive factors of mortality and concluded: In-hospital survival rate of intensive care unit- admitted cirrhotic patients seemed acceptable, even in patients requiring life-sustaining treatments and/or with multiple organ failure on admission. The most important risk factor for in-hospital mortality was the severity of nonhematologic organ failure, as best assessed after 3 days. A trial of unrestricted intensive care for a few days could be proposed for select critically ill cirrhotic patients.

Cirrhotic patients in the medical intensive care unit: Early prognosis and long-term survival

Crit Care Med. 2010 Nov;38(11):2108-2116

Pre-hospital RSI by different specialties

This aim of the study was to evaluate the tracheal intubation success rate of doctors drawn from different clinical specialities performing rapid sequence intubation (RSI) in the pre-hospital environment operating on the Warwickshire and Northamptonshire Air Ambulance. Over a 5-year period, RSI was performed in 200 cases (3.1/month).

Failure to intubate was declared if >2 successive attempts were required to achieve intubation or an ETT could not be placed correctly necessitating the use of an alternate airway. Successful intubation occurred in 194 cases, giving a failure rate of 3% (6 cases, 95% CI 0.6 to 5.3%). While no difference in failure rate was observed between emergency department (ED) staff and anaesthetists (2.73% (3/110, 95% CI 0 to 5.7%) vs 0% (0/55, 95% CI 0 to 0%); p=0.55), a significant difference was found when non-ED, non- anaesthetic staff (GP and surgical) were compared to anaesthetists (10.34% (3/29, 95% CI 0 to 21.4%) vs 0%; p=0.04). There was no significant difference associated with seniority of practitioner (p=0.65). The authors conclude that non-anaesthetic practitioners have a higher tracheal intubation failure rate during pre-hospital RSI, which may reflect a lack of training opportunities.

The small numbers of ‘failure’ rates, combined with the definition of failure in this study, make it hard to draw generalisations. Of note is that the paper lists the outcomes of the six patients who met the failed intubation definition, all of whom appear to have had their airway satisfactorily maintained by the RSI practitioner, three by eventual tracheal intubation, one by LMA, and two by surgical airway. More data are needed before whole specialties are judged on the performance of a small group of doctors.

Should non-anaesthetists perform pre-hospital rapid sequence induction? an observational study

Emerg Med J. 2010 Jul 26. [Epub ahead of print]

EM trainee RSI experience

A single centre observational study of rapid sequence intubation (RSI) was performed in a Scottish Emergency Department (ED) over four and a quarter years, followed by a postal survey of ED RSI operators.

There were 329 RSIs during the study period. RSI was performed by emergency physicians (both trained specialists and training grade, or ‘registrar’ doctors) in 288 (88%) patients. Complication rates were low and there were only two failed intubations requiring surgical airways (0.6%). ED registrars were the predominant RSI operator, with 206 patients (63%). ED consultants performed RSIs on 82 (25%) patients, anaesthetic registrars on 31 (9.4%) patients, and anaesthetic consultants on 8 (2.4%) patients. An ED consultant was present during every RSI performed and an anaesthetist was present during 72 (22%). The average number of ED registrars during this period of training was 8. This equates to each ED trainee performing approximately 26 ED RSIs (6.5 RSIs/year). On average, ED consultants performed 14 RSIs during this period (approx 3.5 RSIs/year). Of the 17 questionnaires, 12 were completed, in all of which cases the trainees were confident to perform RSI independently at the end of registrar training. Interestingly, 45 (14%) of the RSIs in the study were done in the pre-hospital environment by ED staff, two thirds of which were done by ED consultants.

Training and competency in rapid sequence intubation: the perspective from a Scottish teaching hospital emergency department

Emerg Med J. 2010 Sep 15. [Epub ahead of print]

AED Use in Children Now Includes Infants

From the new 2010 resuscitation guidelines:

For attempted defibrillation of children 1 to 8 years of age with an AED, the rescuer should use a pediatric dose-attenuator system if one is available. If the rescuer provides CPR to a child in cardiac arrest and does not have an AED with a pediatric dose-attenuator system, the rescuer should use a standard AED. For infants (<1 year of age), a manual defibrillator is preferred. If a manual defibrillator is not available, an AED with pediatric dose attenuation is desirable. If neither is available, an AED without a dose attenuator may be used.

Summary: Adult AEDs may be used in all infants and children if there is no child-specific alternative

Highlights of the 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for CPR and ECC

Resuscitation Guideline Changes

CAB rather than ABC

The 2010 ILCOR resuscitation guidelines were published today. Key changes and continued points of emphasis from the 2005 BLS Guidelines include the following:

- Sequence change to chest compressions before rescue breaths (CAB rather than ABC)

- Immediate recognition of sudden cardiac arrest based on assessing unresponsiveness and absence of normal breathing (ie, the victim is not breathing or only gasping)

- “Look, Listen, and Feel” removed from the BLS algorithm

- Encouraging Hands-Only (chest compression only) CPR (ie, continuous chest compression over the middle of the chest) for the untrained lay-rescuer

- Health care providers continue effective chest compressions/CPR until return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) or termination of resuscitative efforts

- Increased focus on methods to ensure that high-quality CPR (compressions of adequate rate and depth, allowing full chest recoil between compressions, minimizing interruptions in chest compressions and avoiding excessive ventilation) is performed

- Continued de-emphasis on pulse check for health care providers

- A simplified adult BLS algorithm is introduced with the revised traditional algorithm

- Recommendation of a simultaneous, choreographed approach for chest compressions, airway management, rescue breathing, rhythm detection, and shocks (if appropriate) by an integrated team of highly-trained rescuers in appropriate settings

2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Part 5: Adult Basic Life Support

Circulation. 2010;122:S685-S705

http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/122/18_suppl_3/S685

New CPR Guidelines

The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation has published its five-yearly update of resuscitation guidelines.

The American Heart Association Guidelines can be accessed here

The European Resuscitation Guidelines can be accessed here

2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science

Circulation. 2010;122:S639