![]() Notes from Days 2 & 3 of the London Trauma Conference

Notes from Days 2 & 3 of the London Trauma Conference

Day 2 of the LTC was really good. There were some cracking speakers who clearly had the ‘gift’ when it comes to entertaining the audience. No death by PowerPoint here (although it seems Keynote is now the presentation software of choice!). The theme of the day was prehospital care and major incidents.

The golden nuggets to take away include: (too many to list all of course)

- ‘Pull’ is the key to rapid extrication from cars if time critical from the Norweigan perspective. Dr Lars Wik of the Norweigen air ambulance presented their method of rapid extrication. Essentially they drag the car back on the road or away from what ever it has crashed into to control the environment and make space (360 style). They put a paramedic in the car whilst this is happening. They then make a cut in the A post near the roof, secure the rear of the car to a fire truck or fixed object with a chain and put another chain around the lower A post and steering wheel that is then winched tight. This has the effect of ‘reversing’ the crash and a few videos showed really fast access to the patient. The car seems to peel open. As they train specifically for it, there doesn’t seem to be any safety problems so far and its much quicker than their old method. I guess it doesnt matter really how you organise a rapid extrication method as long as it is trained for and everyone is on the same page.

- Dr Bob Winter presented his thoughts on hangings – to date no survivor of a non-judicial hanging has had a C-spine injury, so why do we collar them? Also there seems no point in cooling them. All imaging and concern for these patients should be based on the significant soft tissue injury that can be caused around the neck.

- Drownings – if the patient is totally submerged probably reasonable to search for 30mins in water that is >6 degrees or 90mins if <6 degrees. After that it becomes a body recovery (unless there is an air pocket or some exceptional circumstance). Patients that have drowned should have early ventilatory support if they show any signs of resp distress.

- Drs Julian Thompson and Mark Byers reassured us on a variety of safety issues at major incidents. It seems the risk to rescuers from secondary bombs at scene is low. Very few terrorist attacks world wide, ever, have had secondary devices so rescuers should be reassured (a bit). Greatest risk to the rescuer, like always, are the silly simple things that are a risk every day, like tripping over your own feet! With reference to chemical incidents, simple PPE seems to be sufficient for the vast majority of incidents, even fairly significant chemical ones, all this mucking about in full air tight suits is probably pointless and means patients cant be treated (at all). This led to the debate of how much risk should we, as rescue staff, accept? Clearly there are no absolute answers but minimising all risk to the rescuer is often at conflict with your ability to rescue. Where the balance should lie is a matter for organisations and individuals I guess.

Sir Prof Keith Porter also gave us an update on the future of Prehospital emergency medicine as a recognised medical specialty. As those in the know, know, the specialty has been recognised by the GMC and the first draft of trainees are currently in post. More deaneries will be following suit soon to begin training but it is likely to take some time to build up large numbers of trained specialists. Importantly for those of us who already have completed our training there will be an option to sub specialise in PHEM but it will involve undertaking the FIMC exam. Great, more exams – see you there.

Sir Prof Keith Porter also gave us an update on the future of Prehospital emergency medicine as a recognised medical specialty. As those in the know, know, the specialty has been recognised by the GMC and the first draft of trainees are currently in post. More deaneries will be following suit soon to begin training but it is likely to take some time to build up large numbers of trained specialists. Importantly for those of us who already have completed our training there will be an option to sub specialise in PHEM but it will involve undertaking the FIMC exam. Great, more exams – see you there.

Day 3 – Major trauma

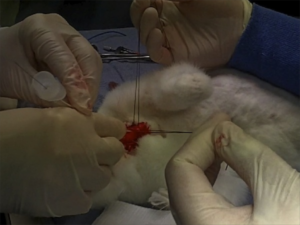

The focus of day 3 was that of damage control. Damage control surgery and damage control resucitation. We had indepth discussions about how to manage pelvic trauma and some of the finer points of trauma resuscitation.

Specific points raised were:

- Pelvic binders are great and can replace an ex fix if the abdomen needs opening to fix a spleen for example.

- You can catheterise patients with pelvic fractures (one gentle try).

- Most pelvic bleeds are venous which is why surgeons who can pack a pelvis is better than a radiologist who can mainly only treat arterial bleeds.

- Coagulopathy in trauma is not DIC and is probably caused by peripheral hypoperfusion.

- All the standard clotting tests that we use (INR etc) are useless and take too long to do. ROTEM or TEG is much better but still not perfect.

Also, as I am sure will please many – pressure isn’t flow so dont use pressors in trauma!

Chris Hill is an emergency and prehospital care physician based in the United Kingdom