My talk at the SmaccGOLD conference in March 2014

Cliff Reid – When Should Resuscitation Stop from Social Media and Critical Care on Vimeo.

Here are the slides:

My talk at the SmaccGOLD conference in March 2014

Cliff Reid – When Should Resuscitation Stop from Social Media and Critical Care on Vimeo.

Here are the slides:

![]() A paediatric trauma centre study showed that in their system, seven people at the bedside was the optimum number to get tasks done in a paediatric resuscitation. As numbers increased beyond this, there were ‘diminishing marginal returns’, ie. the output (tasks completed) generated from an additional unit of input (extra people) decreases as the quantity of the input rises.

A paediatric trauma centre study showed that in their system, seven people at the bedside was the optimum number to get tasks done in a paediatric resuscitation. As numbers increased beyond this, there were ‘diminishing marginal returns’, ie. the output (tasks completed) generated from an additional unit of input (extra people) decreases as the quantity of the input rises.

The authors comment that after a saturation point is reached, “additional team members contribute negative returns, resulting in fewer tasks completed by teams with the most members. This pattern has been demonstrated in other medical groups, with larger surgical teams having prolonged operative times and larger paramedic crews delaying the performance of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.”

There are several possible explanations:

In my view, excessive team size results in there being more individuals to supervise & monitor, and hence a greater cognitive load for the team leader (cue the resus safety officer). More crowding and obstruction threatens situational awareness. There is more difficulty in providing clear uninterrupted closed loop communication. And general resuscitation room entropy increases, requiring more energy to contain or reverse it.

However, for paediatric resuscitations requiring optimal concurrent activity to progress the resuscitation, I do struggle with less than five. Unless of course I’m in my HEMS role, when the paramedic and I just crack on.

More on Making Things Happen in resus.

Own The Resus talk

Resus Room Management site

Factors Affecting Team Size and Task Performance in Pediatric Trauma Resuscitation.

Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014 Mar 19. [Epub ahead of print]

[EXPAND Abstract]

OBJECTIVES: Varying team size based on anticipated injury acuity is a common method for limiting personnel during trauma resuscitation. While missing personnel may delay treatment, large teams may worsen care through role confusion and interference. This study investigates factors associated with varying team size and task completion during trauma resuscitation.

METHODS: Video-recorded resuscitations of pediatric trauma patients (n = 201) were reviewed for team size (bedside and total) and completion of 24 resuscitation tasks. Additional patient characteristics were abstracted from our trauma registry. Linear regression was used to assess which characteristics were associated with varying team size and task completion. Task completion was then analyzed in relation to team size using best-fit curves.

RESULTS: The average bedside team ranged from 2.7 to 10.0 members (mean, 6.5 [SD, 1.7]), with 4.3 to 17.7 (mean, 11.0 [SD, 2.8]) people total. More people were present during high-acuity activations (+4.9, P < 0.001) and for patients with a penetrating injury (+2.3, P = 0.002). Fewer people were present during activations without prearrival notification (-4.77, P < 0.001) and at night (-1.25, P = 0.002). Task completion in the first 2 minutes ranged from 4 to 19 (mean, 11.7 [SD, 3.8]). The maximum number of tasks was performed at our hospital by teams with 7 people at the bedside (13 total).

CONCLUSIONS: Resuscitation task completion varies by team size, with a nonlinear association between number of team members and completed tasks. Management of team size during high-acuity activations, those without prior notification, and those in which the patient has a penetrating injury may help optimize performance.

[/EXPAND]

![]() I’m not a hero and don’t claim to be, but when I was given this talk to do for the SMACC 2013 conference I researched the topic and realised I’d worked with several of them.

I’m not a hero and don’t claim to be, but when I was given this talk to do for the SMACC 2013 conference I researched the topic and realised I’d worked with several of them.

The talk was the toughest I’ve ever given, because I cried while giving it, and knew that it wouldn’t just be the large audience in front of me who would know I was a wuss, but that it was being recorded for many others to find out too!

A full transcript of the talk, the slide set, and links to references from the talk can be found here.

![]() Families allowed to be present during attempted cardiopulmonary resuscitation had improved psychological outcomes at ninety days.

Families allowed to be present during attempted cardiopulmonary resuscitation had improved psychological outcomes at ninety days.

Adult family members of adult patients were studied in this randomized study from France.

Resuscitation team member stress levels and effectiveness of resuscitation did not appear to be affected by family presence.

Family Presence during Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

N Engl J Med. 2013 Mar 14;368(11):1008-18

[EXPAND Abstract]

BACKGROUND: The effect of family presence during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) on the family members themselves and the medical team remains controversial.

METHODS: We enrolled 570 relatives of patients who were in cardiac arrest and were given CPR by 15 prehospital emergency medical service units. The units were randomly assigned either to systematically offer the family member the opportunity to observe CPR (intervention group) or to follow standard practice regarding family presence (control group). The primary end point was the proportion of relatives with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)-related symptoms on day 90. Secondary end points included the presence of anxiety and depression symptoms and the effect of family presence on medical efforts at resuscitation, the well-being of the health care team, and the occurrence of medicolegal claims.

RESULTS: In the intervention group, 211 of 266 relatives (79%) witnessed CPR, as compared with 131 of 304 relatives (43%) in the control group. In the intention-to-treat analysis, the frequency of PTSD-related symptoms was significantly higher in the control group than in the intervention group (adjusted odds ratio, 1.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.2 to 2.5; P=0.004) and among family members who did not witness CPR than among those who did (adjusted odds ratio, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.1 to 2.5; P=0.02). Relatives who did not witness CPR had symptoms of anxiety and depression more frequently than those who did witness CPR. Family-witnessed CPR did not affect resuscitation characteristics, patient survival, or the level of emotional stress in the medical team and did not result in medicolegal claims.

CONCLUSIONS: Family presence during CPR was associated with positive results on psychological variables and did not interfere with medical efforts, increase stress in the health care team, or result in medicolegal conflicts.

[/EXPAND]

A consistent issue that recurs during discussions with UK emergency medicine colleagues is that of having to rely on anaesthesia and/or ICU colleagues for intubation of their patients in the ED. The pain comes not from disagreeing about who does the procedure or what drugs to use, but rather on the decision to intubate.

The refusal to intubate can stall or halt a resuscitation plan, delay care, result in risky transfers to the imaging suite, and even deny potential outcome-improving therapy (for example post-ROSC cooling). It can undermine team leadership and disrupt the team dynamic.

There are often different ways to ‘skin a cat’ and it is frequently helpful to invite the opinion of other critical care specialists. However, it is clear from multiple discussions with frustrated EM colleagues that the decision not to intubate is often influenced by non-clinical factors, most often ICU bed availability. Other times, it appears to be that the ‘gatekeeper’ to airway care (and to ICU beds) does not share the same appreciation of the clinical issues at stake. Examples here include the self-fulfilling pessimism post-ROSC based on inappropriate assignment of predictive value to neurological signs, and the assumption of non-treatable pathology in elderly patients presenting with coma.

The obvious solution to this is that the responsibility for managing the ‘A’ of ABC should not be delegated to non-emergency medicine personnel. Sadly, this is not achievable 24/7 in all UK departments right now for a number of awkward reasons.

So what’s a team leader to do when faced with a colleague’s refusal to intubate? The best approach would be to gently and politely persuade them to change their mind by stating some clinical facts that enable a shared mental model and agreed management plan, and to ensure the most senior available physicians are participating in the discussion.

Sometimes that fails. What next? Here’s a suggestion. This is slightly tongue-in-cheek but take away from it what you will.

It is imperative that the individual declining intubation appreciates the gravity of his or her decision. They must not be under the impression that they’ve done you (and the patient) a favour by giving their opinion after an ‘airway consult’. They have declined a resuscitative intervention requested by the emergency medicine team leader and should appreciate the consequences of this decision and the need to document it as such.

Perhaps say something along the lines of:

And here’s the form. It is provocative, cheeky, and in no way should really be used in its current form:

The talks from SMACC 2013 – the best critical conference ever (so far) – are being made available.

Here’s my talk on Making Things Happen.

Video:

An audio only version is available here:

References from the talk and the slide set are available here

For more SMACC talks susbscribe via iTunes or keep an eye on the Intensive Care Network site

![]() The whole purpose behind my career and this blog is to save life. Like most emergency physicians I don’t see a huge number of resuscitation patients myself in a given week, so my best hope in making a difference is to develop my teaching skills so that I can motivate and inspire others to improve their ability to manage resuscitation.

The whole purpose behind my career and this blog is to save life. Like most emergency physicians I don’t see a huge number of resuscitation patients myself in a given week, so my best hope in making a difference is to develop my teaching skills so that I can motivate and inspire others to improve their ability to manage resuscitation.

The highlight of my week therefore has been the receipt of some email feedback from a colleague in Germany. An intensivist, internist, and prehospital doctor (I like him already) who tells me he found my ‘Own the Resus‘ talk helpful:

Dear Dr. Reid,

Few days ago, too tired too sleep after a long shift on my ICU (18 beds internal medicine ICU, I am specialist in internal medicine specialized in intensive care and prehospital emergency medicine in a major German city) I watched your talk via emcrit podcast. I was immediately caught, I soaked in every word, I was fascinated, watched it twice in the middle of the night and next afternoon I listened to it in my car driving to work.

At this very day I did some overdue crap beyond the end of my shift when I heard the ominous shuffling of feet and rolling of the emergency cart from the other end of the ward… “I think we need your help….”

There it was, difficult airway situation. Patient crashing.

Then what followed was a kind of “out of body experience”. I did what was necessary, made things happen like calling anesthesia difficult airway code, calling the surgeons, organizing fiber optics and meanwhile trying to secure that airway myself until i could dispatch anesthesia to the head and surgeons to the neck. Within few minutes there were 6 doctors and 5 nurses shuffling on 9 square meters…

I found myself 1 meter behind the foot end of the pts bed and with your talk in my head I found me consciously controlling the crowd. There was suddenly the messages of your talk and there was me. I don’t know how to put it into words, I wouldn’t have done something else in medical terms but thanks to your talk I had the vocabulary, the tools to reflect myself as the leader to be in charge of the situation somehow with more distance, and after a successful resus the 10 people involved in this code went off with a good feeling that everybody contributed in what they could and all for the pts benefit.

Your talk was a kind of transition to the next level for me: from the colleague who asks how to get out of trouble in many situations because he was often deeply in trouble, to the one who leads out of trouble.

With your talk many things suddenly became clear and I am looking forward to be able to work harder on this role of leading.

Thank you very much.

D

If you’re in the United Kingdom on Thursday 21st March please consider watching BBC’s Horizon program at 9pm on BBC2.

If you’re in the United Kingdom on Thursday 21st March please consider watching BBC’s Horizon program at 9pm on BBC2.

I’m in Australia so I’ll miss it, but I’m moved by the whole background to this endeavour and really want you to help me spread the word.

Many of you will be familiar with the tragic case of Mrs Elaine Bromiley, who died from hypoxic brain injury after clinicians lost control of her airway during an anaesthetic for elective surgery. Her husband Martin has heroically campaigned for a greater awareness of the need to understand human factors in healthcare so such disasters can be prevented in the future.

Mr Bromiley describes the program, which is hosted by intensivist and space medicine expert Dr Kevin Fong:

Kevin and the Horizon team have produced something inspirational yet scientific, and – just as importantly – it’s by a clinician, for clinicians. It’s written in a way that will appeal to both those in healthcare and the public. It uses a tragic death to highlight human factors that all of us are prone to, and looks at how we can learn from others both in and outside healthcare to make a real difference in the future.

The lessons of this programme are for everyone in healthcare.

It would be wonderful if you could pass on details of the programme to anyone you know who works in healthcare. My goal is that by the end of this week, every one of the 1 million or so people who work in healthcare in the UK will be able to watch it (whether on Thursday or on iPlayer).

From the Health Foundation blog

Please help us reach this 1000 000 viewer target by watching on Thursday or later on iPlayer. Tweet about it or forward this message to as many healthcare providers you know. Help Martin help the rest of us avoid the kind of tragedy that he and his children have so bravely endured.

For more information on Mrs Bromiley’s case, watch ‘Just a Routine Operation’:

Cliff

I made up a word a while ago: “dogmalysis”. It refers to the dissolution of authoritative tenets held as established opinion without adequate grounds.

I made up a word a while ago: “dogmalysis”. It refers to the dissolution of authoritative tenets held as established opinion without adequate grounds.

DOGMA: something held as an established opinion; a point of view or tenet put forth as authoritative without adequate grounds

LYSIS: a process of disintegration or dissolution (as of cells)

It’s my favourite thing in medicine. I don’t know why – perhaps because of my admiration since childhood for irreverent scientists who questioned authority, like Feynman and Sagan. Or perhaps it is because I think at times we physicians need to experience the humility of having our ignorance exposed. This is necessary to keep medicine science-based.

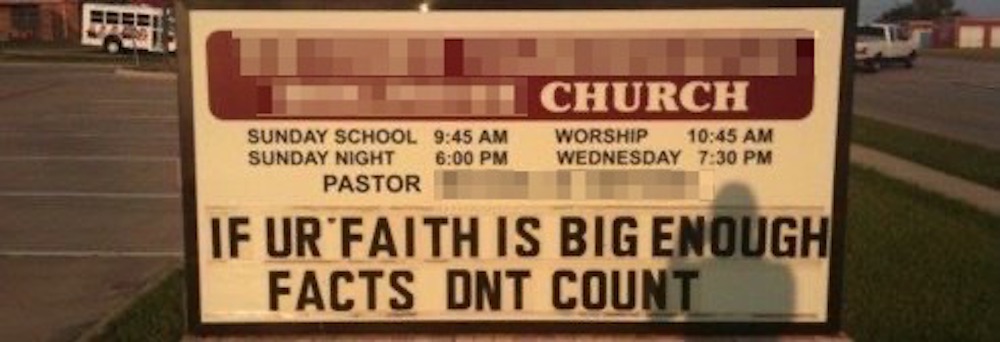

My undergraduate and much of my postgraduate training consisted of being taught medical certainties that I was required to regurgitate under exam conditions. The reality of clinical practice then revealed the awesome irreducible complexity of biology in our patients who ‘don’t read the textbooks’. As we learn in emergency medicine to navigate the perilous Bayesian jungle to a ‘very unlikely’ or ‘very likely’ life-threatening diagnosis, and when we have to weigh up the benefit:harm equation of an intervention that could either kill or cure, we begin to appreciate that certainty without evidence – dogma, or faith – can be lethal.

The problem is, however, that our human brains seem to thrive on it. We have evolved a whole senate of cognitive biases, which enable us to function well in everyday social situations, but which prevent us from conducting an impartial analysis of objective clinical data. An enlightening example of the degree to which our interpretation of the same information can vary is illustrated by a handful of trials on fibrinolytic therapy for stroke, producing a spectrum of reactions from aggressive promotion to skeptical opposition.

Being human, I have no doubt that I am occasionally dogmatic about topics to which I erroneously believe I have applied skepticism. I appreciate the courage of trainees who have the guts to challenge my assertions and who demand the evidence to justify them. Keep doing it. Keep asking. Keep challenging.

Keep lysing the dogma.

No-one said it better than Carl:

I want to clarify some terminology I use on a day-to-day basis, which is now so ingrained in my vocabulary that I forget that its meaning may not be obvious to all.

“You go in there and it looks like a chicken bomb has gone off…”

“..external muppet factors can delay preparation for transport”

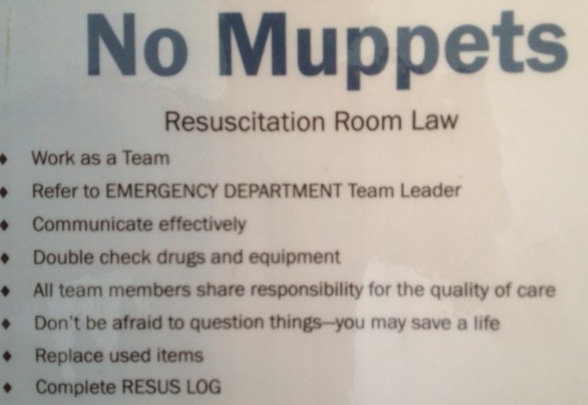

The first is ‘muppet’. This does not refer to the much loved and trademarked invention of Jim Henson, (and now property of Disney) – a word originally thought to be a synthesis of ‘marionette’ and ‘puppet’. If I were referring to these wonderful icons of children’s televisual theatre I would capitalise the ’m’. Nope. I refer to the British meaning, which the Oxford English Dictionary lists as: ‘an incompetent or foolish person’. However I apply it in the context of behaviour rather than character. A wealth of evidence has proven that good people can do bad things given the circumstances, and situational factors can lead us to behave in a way that we would not normally consider to be correct.

The first is ‘muppet’. This does not refer to the much loved and trademarked invention of Jim Henson, (and now property of Disney) – a word originally thought to be a synthesis of ‘marionette’ and ‘puppet’. If I were referring to these wonderful icons of children’s televisual theatre I would capitalise the ’m’. Nope. I refer to the British meaning, which the Oxford English Dictionary lists as: ‘an incompetent or foolish person’. However I apply it in the context of behaviour rather than character. A wealth of evidence has proven that good people can do bad things given the circumstances, and situational factors can lead us to behave in a way that we would not normally consider to be correct.

Certain situations can therefore lead our behaviour to at least appear to be incompetent or foolish. So perfectly good clinicians can appear to act like muppets during a resuscitation, given the circumstances. Various environmental and psychological factors contribute to this. Those factors generated within our own brains or bodies that influence our personal behaviour and performance have been called ‘internal muppet factors’. These include various cognitive errors such as inattention or fixation, or simple physiological stresses like fatigue or hunger. Those that relate to external forces such as environmental pressures or interaction with other team members are grouped under ‘external muppet factors’. These are most often a consequence of poor leadership and communication, and a lack of a shared mental model and agreed mission trajectory.

I had the privilege of working with Norwegian critical care doctor Per Bredmose, aka Viking One. He and I coined the terms internal and external muppet factors as a framework for debriefing resuscitation cases when attempting to understand the human factors involved. This was when we worked together in the UK in Basingstoke, where for the duration of my tenure we had a sign up on the wall in the resus room saying ‘No muppets’ (this now lives in my office in Sydney).

When the external muppet factor is allowed to escalate unchecked, the end result is frenetic activity and noise from the staff without coordinated meaningful intervention for the patient. Comparisons with ‘headless chickens’ are often drawn. In particularly challenging scenarios, it can appear that the panic has swelled to such magnitude that it goes nova, as though the headless chickens have actually exploded, metaphorically filling the room with a gruesome blanket of giblets and a snowstorm of feathers, clouding ones ability to assess and manage the patient effectively. This high-point of group anxiety and ineffectiveness is what I mean by the term ’chicken bomb’, and I bet most readers of this blog will have witnessed the detonation of one.

When the external muppet factor is allowed to escalate unchecked, the end result is frenetic activity and noise from the staff without coordinated meaningful intervention for the patient. Comparisons with ‘headless chickens’ are often drawn. In particularly challenging scenarios, it can appear that the panic has swelled to such magnitude that it goes nova, as though the headless chickens have actually exploded, metaphorically filling the room with a gruesome blanket of giblets and a snowstorm of feathers, clouding ones ability to assess and manage the patient effectively. This high-point of group anxiety and ineffectiveness is what I mean by the term ’chicken bomb’, and I bet most readers of this blog will have witnessed the detonation of one.

I credit the invention of this term to emergency and prehospital physician James French, a master resuscitationist and human factors wizard who also introduced the idea of clinical logistics to us.

So, next time you encounter muppets and chicken bombs, feel free to use the terminology, although preferably not during an actual resus with those who might take it personally.