By Stuart Duffin

By Stuart Duffin

Expat Brit, intensive care physician and anaesthetist at Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden. Stuart trained in the UK, and spent some time working Australian emergency departments.

One of the most striking things for me about our new/old pan-specialty of critical care, brought into focus by the world-shrinking effects of FOAM and twitter, is just how differently it falls into the domains of the established specialities in different parts of the world. This leads inevitably to comments like, “emergency physicians shouldn’t intubate”, “anaesthetists cant do sick”, “nurses cant be doing such and such”, and so on. All of these statements are clearly equally rubbish because obviously, in certain parts of the world, they do. And they do it really well. Sure there are differences between countries and continents, populations and environments, but when it comes down to it, it doesn’t matter where you are, people still get sick, infected, pregnant, run over, stabbed or hit around the head with heavy things.

All over the world, in our previously quite isolated environments, these same ‘selection pressures’ have forced healthcare providers to evolve by the process of convergent evolution. Although obviously not strictly darwinian, the undeniable effects of simultaneous evolution by survival of the fittest-to-practice can be seen.

Convergent evolution is the process by which, in different parts of the world, completely different species have evolved in parallel to fill similar roles and have similar features. It didn’t matter whether it was a deer, a wildebeest or a kangaroo, there was a vacancy for a fairly big animal who liked eating grass and moved in big groups, and someone stepped up.

Unsurprisingly, critical care resuscitationists are also a little different from country to country and from continent to continent. They have different titles and work in slightly different ways. But when you really look at a critical care doc in action, or talk to one, or follow one on Twitter, we are all cut from the same cloth. I would argue that FOAM has created a critical care zoo in which the kangaroos and antelopes, lemurs and monkeys, aardvarks and echidnas and anaesthetists and emergency physicians are all chucked into the same cage. They’re all looking at each other thinking, “you look like me, but somehow not. We seem to do the same stuff, but we’re not identical – it cant be right!”.

In The United States, the idea of an anaesthetist doing a clamshell thoracotomy would be a little strange. In Scandinavia, an emergency physician doing central lines and fiberoptic intubation in resus would be just as eyebrow raising. A Swedish intensivist and anaesthetist spent some time working in Australia as an ICU senior reg. When attending a patient in resus the emergency physician there announced “we need an airway guy”. My colleague answered “I’m the airway guy”. “No an anaesthetist” replied the emergency physican. “I am an anaesthetist!” “No an….” and so it went on.

The effects of this process are of course by no means limited to doctors. Nurses, paramedics and physiotherapists are all part of this still changing ecosystem. A colleague of mine was showing a visiting Australian emergency physician our trauma bay and describing how major trauma is managed here without the involvement of emergency physicians at all. “When it’s really urgent, it’s anaesthesia and surgery” he explained. I wonder how that went down? There is an element of truth to the statement but the words are wrong. It should have been “When it’s really urgent, it’s airway, access, transfusion, invasive procedures and resuscitation thinking”.

The job title of the person who actually holds the knife/laryngoscope/needle and has what it takes to get it done isn’t important. When the push comes to shove and the bad stuff bounces off the fan, it’s more about skillset and mindset, and less about the collection of letters under your name on your badge, or after your name on your CV.

Category Archives: Resus

Life-saving medicine

Advice To A Young Resuscitationist

This talk was the opening plenary given at smacc Chicago. The title they gave me was ‘Advice To A Young Resuscitationist. It’s Up To Us To Save The World‘ but I ditched the last half because, as I point out later in the talk, I don’t think it is up to us to save the whole World. Some AV muppetry at the conference centre prevented the smacc team from being able to include the slides, so I’ll post those too at some point. You can hear the talk as a podcast at the ICN or on iTunes

The references for the talk are here

Learning To Speak Resuscitese

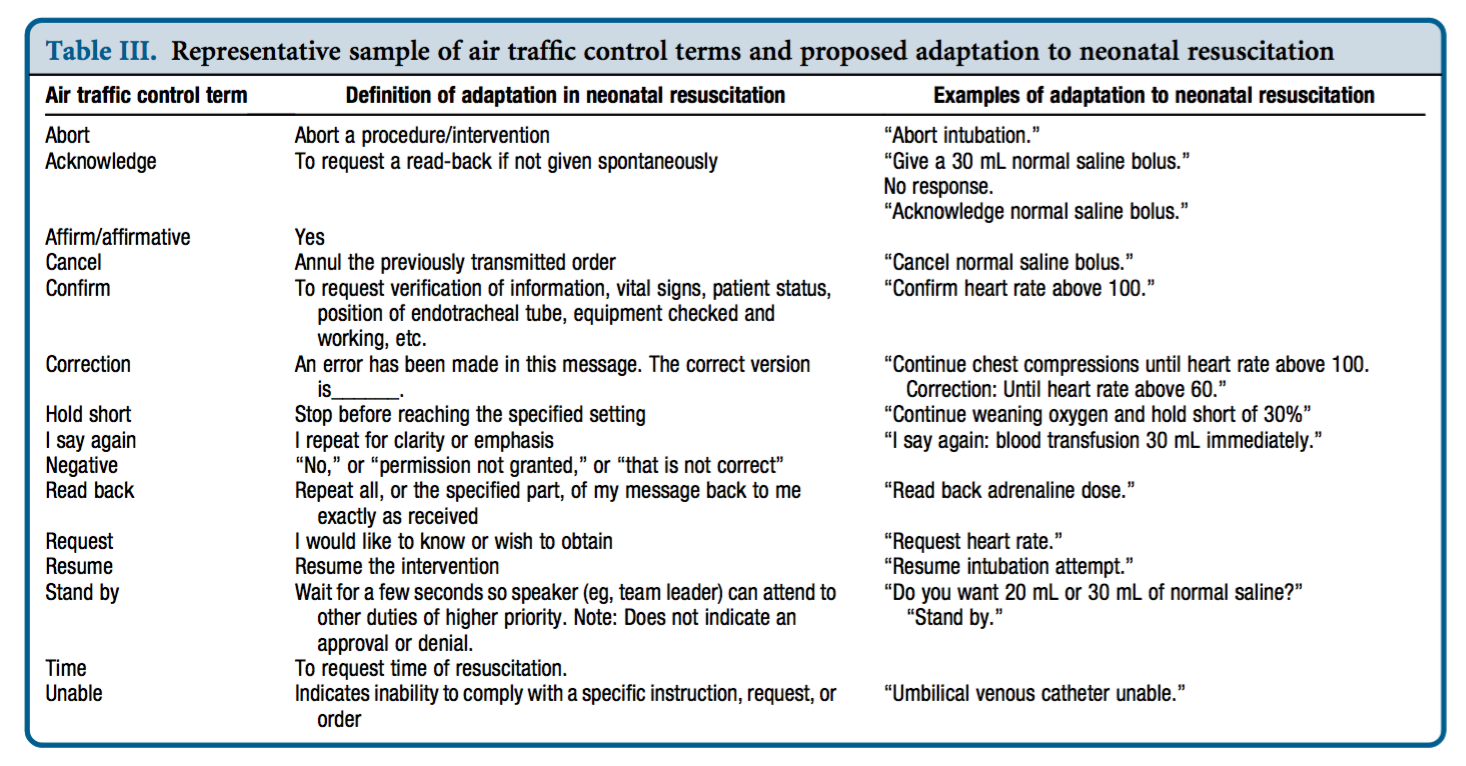

In the resus room, clarity of communication between team members is critical to patient safety and effective resuscitation. We are used to following standardised clinical algorithms for cardiac arrests and many other emergency presentations, but there is no standardisation of vocabulary or communication style. Communication failures are a major source of error in resuscitation, suggesting this is an area in which we need to improve.

Defining your lexicon

A contrast with the aviation industry was drawn by neonatologist Dr Nicole Yamada, who points out that pilots and air traffic controllers use an effective, concise, standardised set of words and phrases that are universally understood, for example ‘stand by’, ‘unable’, ‘read back’, and ‘cancel'(1). She proposed adapting a similar resuscitation-specific lexicon modelled after aviation communication which ‘would aid in streamlining communication during time-pressured clinical situations when seconds count and errors can kill.‘(2)

Dr Yamada tested this approach in a small study of simulated neonatal resuscitation. Standardised communication techniques were associated with a trend toward decreased error rate and faster initiation of critical interventions.(3)

Avoiding the fluff

In the absence of standardised approaches to communication, humans in the resus room often choose language which indirectly acknowledges social hierarchies. For ad hoc teams, phrases may be chosen which are least likely to offend people with whom we’re unfamiliar, or may be deferential in cases of real or presumed authority and expertise gradients. The consequence of this is the use of ‘mitigating language‘. Examples might be:

“Any chance you could pop a line in?”

“Would someone mind letting me know if they can feel a pulse?”

“Do you want to have a think about setting up for intubation?”

“How about we get some bag-mask ventilation happening at some point?”

“If you could have a look at his abdomen that would be awesome”

These commands (imperatives) phrased obliquely as questions or suggestions are know as ‘whimperatives‘ and are found throughout resus room dialogue, when the team leader does not wish to convey the assumption of a power relationship over her colleagues. These whimperatives are an example of ‘mitigating speech’, which refers to language that ‘de-emphasises’ or ‘sugarcoats’ the command.

In the words of Peter Brindley:

‘The danger of mitigating language illustrates why, during medical crises, we should replace comments such as “perhaps, we need a surgeon” or “we should think about intubating” with “get me a surgeon” and “intubate the patient now.”’(4)

Conclusion

There’s nothing wrong with being polite and respectful, and mitigating language may be helpful in the team building phase. However the more critical the situation, the more an authorative/directive leadership style that clearly delegates critical tasks is required(5). Standardised terminology (with closed loop communication) is likely to enhance clarity of the message and accelerate the sharing of a team mental model. Avoiding whimperatives and excessive mitigating phrases may further prevent ambiguity and imprecision, reducing the time to critical interventions.

These components of the content of resus room communication – unequivocal, standardised, and direct – should go hand in hand with the delivery of the words. Effective delivery requires optimal delivery speed and ‘command presence’. These factors will be discussed in a future post.

I’d be interested to hear what standard phrases or words you think should be in the resus-room lexicon.

1. Yamada NK, Halamek LP. Communication during resuscitation: Time for a change? Resuscitation. 2014 Dec;85(12):e191–2.

2. Yamada NK, Halamek LP. On the Need for Precise, Concise Communication during Resuscitation: A Proposed Solution. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2015 Jan;166(1):184–7.

3. Yamada NK, Fuerch JH, Halamek LP. Impact of Standardized Communication Techniques on Errors during Simulated Neonatal Resuscitation. Am J Perinatol. 2016 Mar;33(4):385–92.

4. Brindley PG, Reynolds SF. Improving verbal communication in critical care medicine. Journal of Critical Care. 2011 Apr;26(2):155–9.

5. Bristowe KK, Siassakos DD, Hambly HH, Angouri JJ, Yelland AA, Draycott TJT, et al. Teamwork for clinical emergencies: interprofessional focus group analysis and triangulation with simulation. Qual Health Res. 2012 Sep 30;22(10):1383–94.

Louisa in London – Prehospital Lessons from LTC2015

The London Trauma Conference remains up there on my list of ‘must go’ conferences to attend. It marks the end of the year, fills me with hope and inspires me for the future. Unfortunately this year I was torn between the conference and the demands of clinical directorship so I could only get to the “Air Ambulance & Prehospital Care Day”. At least this way I’m saved from the dilemma of which sessions to attend!

So what were the highlights of the Prehospital Day? For me, they were Prehospital ECMO,’Picking Up the Pieces’, and the REBOA update.

Prehospital ECMO

Professor Pierre Carli gave us an update on prehospital ECMO. Professor Carli (not to be confused with the equally awesome Professor Carley) is the medical director of Service d’Aide Médicale Urgente (SAMU) in Paris. They’ve been doing prehospital ECMO in Paris since 2011 and the data analysed over three years reveals a 10% survival to hospital discharge rate. We know from the work in Asia that successful outcome following traditional cardiac arrest management and ECPR is related to the speed of the intervention. Transposing the time to intervention from his 2011 – 2013 data onto the survival curve that Chen et al produced explains why the success rate is limited:

The revised 2015 process aims to reduce the duration of CPR, reduce time to ECMO and therefore improve survival to discharge rates. They are doing this by dispatching the ECMO team earlier.

The eligibility criteria for ECPR is also changing; patients >18 and <75years, refractory cardiac arrest (defined as failure of ROSC after 20min of CPR), no flow for < 5 minutes with shockable rhythm or signs of life or hypothermia or intoxication, EtCO2 > 10mmHg at time of inclusion and no major comorbidity.

Already there appears to be an improvement with 16 patients treated using the revised protocol with 5 survivors (31%) – although we must be wary of the small numbers.

A concern that was expressed by the French Department of Health was the fear of a reduction in organ donation with the introduction of ECPR – it turns out that rates have remained stable. In fact the condition of non heart beating donated organs is better when ECMO has been instigated; the long term effects on organ donation are being assessed.

I’m without doubt that prehospital ECMO/ED ECMO is the future although currently in the UK our hospital systems aren’t ready for this. If you want to learn more then look at the ED ECMO site or book on one of the many emerging courses on ED ECMO including the one that is run by Dr Simon Finney at the London Trauma Conference, or if you want to go further afield you could try San Diego (although places are fully booked on the next course).

Picking Up the Pieces

The Keynote speaker was Professor Sir Simon Wessely. He is a psychiatrist with a specialist interest in military psychology and his brief was to describe to us the public response to traumatic incidents. He has worked with the military and in civilian situations. After the 7/7 London bombings the population of London was surveyed: those most likely to be affected were of lower social class, of Muslim faith, those that had a relative that was injured, those unsure of the safety of others, those with no previous experience of terrorism and those experiencing difficulty in contacting others by mobile phone. Obviously there are many factors that we cannot influence however on the basis of the last risk factor our response to incidents has changed – the active discouragement to make phone calls has been changed to a recommendation of making short calls to friends and relatives.

The previous practice of offering immediate psychological debriefing to those involved in incidents was discounted by Prof Wessely – his research demonstrated that this intervention was not only not required but could actually result in harm: only a minority have ongoing psychological distress that can benefit from formal psychological input, which should occur later.

The approach that should be taken is to allow that individual to utilise their own social networks (family, friends, and colleagues) and to accept that in some cases the individual may not want or need to talk. This has led to the development of the Trauma Risk Management (TRIM) system which provides individuals within organisations that are exposed to traumatic events the skills required to identify those at risk of developing psychological problems and to recognise the signs and symptoms of those in difficulty. To a certain extent we naturally do this for our peers – I have spent many a night sitting in the ‘Good Samaritan’ pub with colleagues from the Royal London Hospital and London’s Air Ambulance – but having a more formal system is probably of benefit to enable those who have ongoing difficulties to access additional support.

REBOA update

Finally, the REBOA update – Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta. One year on, Dr Sammy Sadek informed us that there are now more courses teaching the REBOA technique than there are (prehospital) patients that have received it. Over the last year only seven patients have qualified for this intervention in London, far fewer than they had anticipated. Another three patients died before REBOA could be instigated. All patients had a positive cardiovascular response. Four of the seven died from causes other than exsanguination. Is it worth all the effort and resource to deliver this intervention when such a select group will benefit?

Obviously there was much more covered in the day, this is just a taste. If you’ve never been to the London Trauma Conference then I definitely would recommend it and even if you have been before there are so many breakout sessions now there is always something for everyone.

More on the London Trauma Conference:

- Keep an eye on the LTC website for information on the 2016 conference.

- Follow the #LTC2015 Twitter feed

- Read and listen to the excellent summaries at St Emlyn’s

Merry Christmas and see you next year!

Louisa Chan

What It Takes To Be At The Cutting Edge

This talk was presented at the Royal College of Emergency Medicine Annual Scientific Meeting in Manchester in September 2015.

You can download the audio here, listen online here, or find it in iTunes at the RCEM FOAMed Network here.

A brief summary of the talk and related references are here.

Dabigatran Reversal Agent – Idarucizumab

Thanks to Rob MacSweeney‘s fantastic Critical Care Reviews I learned of Idarucizumab, a monoclonal antibody fragment that binds the (pesky) anticoagulant dabigatran. Two industry-supported studies this week show rapid, complete reversal of anticoagulation in healthy volunteers(1) and patients who were either bleeding or undergoing procedures(2). The dose given to patients was 5g intravenously.

An accompanying editorial(3) highlights that the clinical study did not have a control group, and these patients had a high mortality. Further controlled studies examining patient-orientated outcomes will be helpful.

Of interest, another editorialist(4) lists other potential antidotes for Non-vitamin-K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) that have been or are being tested: an antidote against all oral direct factor Xa inhibitors called andexanet alpha (a recombinant activated factor X that binds direct factor Xa inhibitors), and a modified thrombin has been shown to be effective in vitro and in animals for reversal of dabigatran and potentially also other direct thrombin inhibitors.

1. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of idarucizumab for the reversal of the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran in healthy male volunteers: a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 1 trial

The Lancet Volume 386, No. 9994, p680–690, 15 August 2015

[EXPAND Abstract]

BACKGROUND: Idarucizumab is a monoclonal antibody fragment that binds dabigatran with high affinity in a 1:1 molar ratio. We investigated the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of increasing doses of idarucizumab for the reversal of anticoagulant effects of dabigatran in a two-part phase 1 study (rising-dose assessment and dose-finding, proof-of-concept investigation). Here we present the results of the proof-of-concept part of the study.

METHODS: In this randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, proof-of-concept phase 1 study, we enrolled healthy volunteers (aged 18-45 years) with a body-mass index of 18·5-29·9 kg/m2 into one of four dose groups at SGS Life Sciences Clinical Research Services, Belgium. Participants were randomly assigned within groups in a 3:1 ratio to idarucizumab or placebo using a pseudorandom number generator and a supplied seed number. Participants and care providers were masked to treatment assignment. All participants received oral dabigatran etexilate 220 mg twice daily for 3 days and a final dose on day 4. Idarucizumab (1 g, 2 g, or 4 g 5-min infusion, or 5 g plus 2·5 g in two 5-min infusions given 1 h apart) was administered about 2 h after the final dabigatran etexilate dose. The primary endpoint was incidence of drug-related adverse events, analysed in all randomly assigned participants who received at least one dose of dabigatran etexilate. Reversal of diluted thrombin time (dTT), ecarin clotting time (ECT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and thrombin time (TT) were secondary endpoints assessed by measuring the area under the effect curve from 2 h to 12 h (AUEC2-12) after dabigatran etexilate ingestion on days 3 and 4. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01688830.

FINDINGS: Between Feb 23, and Nov 29, 2013, 47 men completed this part of the study. 12 were enrolled into each of the 1 g, 2 g, or 5 g plus 2·5 g idarucizumab groups (nine to idarucizumab and three to placebo in each group), and 11 were enrolled into the 4 g idarucizumab group (eight to idarucizumab and three to placebo). Drug-related adverse events were all of mild intensity and reported in seven participants: one in the 1 g idarucizumab group (infusion site erythema and hot flushes), one in the 5 g plus 2·5 g idarucizumab group (epistaxis); one receiving placebo (infusion site haematoma), and four during dabigatran etexilate pretreatment (three haematuria and one epistaxis). Idarucizumab immediately and completely reversed dabigatran-induced anticoagulation in a dose-dependent manner; the mean ratio of day 4 AUEC2-12 to day 3 AUEC2-12 for dTT was 1·01 with placebo, 0·26 with 1 g idarucizumab (74% reduction), 0·06 with 2 g idarucizumab (94% reduction), 0·02 with 4 g idarucizumab (98% reduction), and 0·01 with 5 g plus 2·5 g idarucizumab (99% reduction). No serious or severe adverse events were reported, no adverse event led to discontinuation of treatment, and no clinically relevant difference in incidence of adverse events was noted between treatment groups.

INTERPRETATION: These phase 1 results show that idarucizumab was associated with immediate, complete, and sustained reversal of dabigatran-induced anticoagulation in healthy men, and was well tolerated with no unexpected or clinically relevant safety concerns, supporting further testing. Further clinical studies are in progress.

[/EXPAND]

2. Idarucizumab for Dabigatran Reversal

N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 6;373(6):511-20

[EXPAND Abstract]

BACKGROUND: Specific reversal agents for non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants are lacking. Idarucizumab, an antibody fragment, was developed to reverse the anticoagulant effects of dabigatran.

METHODS: We undertook this prospective cohort study to determine the safety of 5 g of intravenous idarucizumab and its capacity to reverse the anticoagulant effects of dabigatran in patients who had serious bleeding (group A) or required an urgent procedure (group B). The primary end point was the maximum percentage reversal of the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran within 4 hours after the administration of idarucizumab, on the basis of the determination at a central laboratory of the dilute thrombin time or ecarin clotting time. A key secondary end point was the restoration of hemostasis.

RESULTS: This interim analysis included 90 patients who received idarucizumab (51 patients in group A and 39 in group B). Among 68 patients with an elevated dilute thrombin time and 81 with an elevated ecarin clotting time at baseline, the median maximum percentage reversal was 100% (95% confidence interval, 100 to 100). Idarucizumab normalized the test results in 88 to 98% of the patients, an effect that was evident within minutes. Concentrations of unbound dabigatran remained below 20 ng per milliliter at 24 hours in 79% of the patients. Among 35 patients in group A who could be assessed, hemostasis, as determined by local investigators, was restored at a median of 11.4 hours. Among 36 patients in group B who underwent a procedure, normal intraoperative hemostasis was reported in 33, and mildly or moderately abnormal hemostasis was reported in 2 patients and 1 patient, respectively. One thrombotic event occurred within 72 hours after idarucizumab administration in a patient in whom anticoagulants had not been reinitiated.

CONCLUSIONS: Idarucizumab completely reversed the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran within minutes. (Funded by Boehringer Ingelheim; RE-VERSE AD ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT02104947.).

[/EXPAND]

3. Targeted Anti-Anticoagulants

N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 6;373(6):569-71

4. Antidotes for anticoagulants: a long way to go

The Lancet Volume 386, No. 9994, p634–636, 15 August 2015

Inhaled nitric oxide: a tool for all resuscitationists?

The use of inhaled nitric oxide is established in certain groups of patients: it improves oxygenation (but not survival) in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome(1), and it is used in neonatology for management of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn(2). But it can be applied in other resuscitation settings: in arrested or peri-arrest patients with pulmonary hypertension.

The use of inhaled nitric oxide is established in certain groups of patients: it improves oxygenation (but not survival) in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome(1), and it is used in neonatology for management of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn(2). But it can be applied in other resuscitation settings: in arrested or peri-arrest patients with pulmonary hypertension.

Read this (modified) description of a case managed by one of my resuscitationist friends from an overseas location:

She developed extreme pulmonary hypertension with suprasystemic pulmonary artery pressures, and she went down the pulmonary HT spiral as I stood there. On ultrasound her distended RV was making her LV totally collapse. She arrested. Futile CPR was started.

I have never had an extreme pulmonary HT survive an arrest. I grabbed a bag and rapidly set up a manual inhaled Nitric Oxide system and bagged and begged…

She achieved ROSC after some minutes. A repeat ultrasound showed a well functioning LV and less dilated RV.

Today, after 12 hours she is opening her eyes and obeying commands. Still a long way to go, but alive.

It sounds impressive. I don’t have more case details, and don’t know how confident they could be about the diagnosis of amniotic fluid embolism but the presentation certainly fits with acute pulmonary hypertension with RV failure. The use of inhaled nitric oxide has certainly been described for similar scenarios before(3). But it raises bigger questions: is this something we should all be capable of? Are there cardiac arrests involving or caused by pulmonary hypertension that will not respond to resuscitation without nitric oxide?

Nitric oxide

Inhaled nitric oxide is a pulmonary vasodilator. It decreases right-ventricular afterload and improves cardiac index by selectively decreasing pulmonary vascular resistance without causing systemic hypotension(4).

RV failure and pulmonary hypertension

Patients may become shocked or suffer cardiac arrest due to acute right ventricular dysfunction. This may be due to a primary cardiac cause such as right ventricular infarction (always consider this in a hypotensive patient with inferior STEMI, and confirm with a right ventricular ECG and/or echo). Alternatively it could be due to a pulmonary or systemic cause resulting in severe pulmonary hypertension, causing secondary right ventricular dysfunction. The commonest causes of acute pulmonary hypertension are massive PE, sepsis, and ARDS(5).

The haemodynamic consequences of RV failure are reduced pulmonary blood flow and inadequate left ventricular filling, leading to decreased cardiac output, shock, and arrest. In severe acute pulmonary hypertension the RV distends, resulting in a shift of the interventricular septum which compresses the LV and further inhibits LV filling (the concept of ventricular interdependence).

What’s wrong with standard ACLS?

In some patients with PHT who arrest, CPR may be ineffective due to a failure to achieve adequate pulmonary blood flow and ventricular filling. In one study of patients with known chronic PHT who arrested in the ICU, survival rates even for ventricular fibrillation were extremely poor and when measured end tidal carbon dioxide levels were very low. In the same study it was noted that some of the survivors had received an intravenous bolus administration of iloprost, a prostacyclin analogue (and pulmonary vasodilator) during CPR(6).

CPR may therefore be ineffective. Intubation and positive pressure ventilation may also be associated with haemodynamic deterioration in PHT patients(7), and intravenous epinephrine (adrenaline) has variable effects on the pulmonary circulation which could be deleterious(8).

If inhaled nitric oxide (iNO) can improve pulmonary blood flow and reduce right ventricular afterload, it could theoretically be of value in cases of shock or arrest with RV failure, especially in cases of pulmonary hypertension; these are patients who otherwise have poor outcomes and may not benefit from CPR.

Is the use of iNO described in shock or arrest?

Numerous case reports and series demonstrate recovery from shock or arrest following nitric oxide use in various situations of decompensated right ventricular failure from pulmonary hypertension secondary to pulmonary fibrotic disease(9), pneumonectomy surgery(10), and pulmonary embolism(11) including post-embolectomy(12).

Acute hemodynamic improvement was demonstrated following iNO therapy in a series of right ventricular myocardial infarction patients with cardiogenic shock(13).

A recent systematic review of inhaled nitric oxide in acute pulmonary embolism documented improvements in oxygenation and hemodynamic variables, “often within minutes of administration of iNO”. The authors state that these case reports underscore the need for randomised controlled trials to establish the safety and efficacy of iNO in the treatment of massive acute PE(14).

Why aren’t they telling us to use it?

If iNO may be helpful in certain cardiac arrest patients, why isn’t ILCOR recommending it? Actually it is mentioned – in the context of paediatric life support. The European Resuscitation Council states:

There is an increased risk of cardiac arrest in children with pulmonary hypertension.

Follow routine resuscitation protocols in these patients with emphasis on high FiO2 and alkalosis/hyperventilation because this may be as effective as inhaled nitric oxide in reducing pulmonary vascular resistance.

Resuscitation is most likely to be successful in patients with a reversible cause who are treated with intravenous epoprostenol or inhaled nitric oxide.

If routine medications that reduce pulmonary artery pressure have been stopped, they should be restarted and the use of aerosolised epoprostenol or inhaled nitric oxide considered.

Right ventricular support devices may improve survival

Should we use it?

So if acute (or acute on chronic) pulmonary hypertension can be suspected or demonstrated based on history, examination, and echo findings, and the patient is in extremis, it might be anticipated that standard ACLS approaches are likely to be futile (as they often are if the underlying cause is not addressed). One might consider attempts to induce pulmonary vasodilation to improve pulmonary blood flow and LV filling, improving oxygenation, and reducing RV afterload as means of reversing acute cor pulmonale.

Are there other pulmonary vasodilators we can use?

iNO is not the only means of inducing pulmonary vasodilation. Oxygen, hypocarbia (through hyperventilation)(15), and alkalosis are all known pulmonary vasodilators, the latter providing an argument for intravenous bicarbonate therapy from some quarters(16). Prostacyclin is a cheaper alternative to iNO(17) and can be given by inhalation or intravenously, although is more likely to cause systemic hypotension than iNO. Some inotropic agents such as milrinone and levosimendan can lower pulmonary vascular resistance(18).

What’s the take home message?

The take home message for me is that acute pulmonary hypertension provides yet another example of a condition that requires the resuscitationist to think beyond basic ACLS algorithms and aggressively pursue and manage the underlying cause(s) of shock or arrest. Inhaled pulmonary vasodilators may or may not be available but, as always, whatever resources and drugs are used, they need to be planned for well in advance. What’s your plan?

References

1. Adhikari NKJ, Dellinger RP, Lundin S, Payen D, Vallet B, Gerlach H, et al.

Inhaled Nitric Oxide Does Not Reduce Mortality in Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Regardless of Severity.

Critical Care Medicine. 2014 Feb;42(2):404–12

2. Steinhorn RH.

Neonatal pulmonary hypertension.

Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2010 Mar;11:S79–S84 Full text

3. McDonnell NJ, Chan BO, Frengley RW.

Rapid reversal of critical haemodynamic compromise with nitric oxide in a parturient with amniotic fluid embolism.

International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia. 2007 Jul;16(3):269–73

4. Creagh-Brown BC, Griffiths MJ, Evans TW.

Bench-to-bedside review: Inhaled nitric oxide therapy in adults.

Critical Care. 2009;13(3):221 Full text

5. Tsapenko MV, Tsapenko AV, Comfere TB, Mour GK, Mankad SV, Gajic O.

Arterial pulmonary hypertension in noncardiac intensive care unit.

Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4(5):1043–60 Full text

6. Hoeper MM, Galié N, Murali S, Olschewski H, Rubenfire M, Robbins IM, et al.

Outcome after cardiopulmonary resuscitation in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension.

American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2002 Feb 1;165(3):341–4.

Full text

7. Höhn L, Schweizer A, Morel DR, Spiliopoulos A, Licker M.

Circulatory failure after anesthesia induction in a patient with severe primary pulmonary hypertension.

Anesthesiology. 1999 Dec;91(6):1943–5 Full text

8. Witham AC, Fleming JW.

The effect of epinephrine on the pulmonary circulation in man.

J Clin Invest. 1951 Jul;30(7):707–17 Full text

9. King R, Esmail M, Mahon S, Dingley J, Dwyer S.

Use of nitric oxide for decompensated right ventricular failure and circulatory shock after cardiac arrest.

Br J Anaesth. 2000 Oct;85(4):628–31. Full text

10. Fernández-Pérez ER, Keegan MT, Harrison BA.

Inhaled nitric oxide for acute right-ventricular dysfunction after extrapleural pneumonectomy.

Respir Care. 2006 Oct;51(10):1172–6 Full text

11. Summerfield DT, Desai H, Levitov A, Grooms DA, Marik PE.

Inhaled Nitric Oxide as Salvage Therapy in Massive Pulmonary Embolism: A Case Series.

Respir Care. 2012 Mar 1;57(3):444–8 Full text

12. Schenk P, Pernerstorfer T, Mittermayer C, Kranz A, Frömmel M, Birsan T, et al.

Inhalation of nitric oxide as a life-saving therapy in a patient after pulmonary embolectomy.

Br J Anaesth. 1999 Mar;82(3):444–7 Full text

13. Inglessis I, Shin JT, Lepore JJ, Palacios IF, Zapol WM, Bloch KD, et al.

Hemodynamic effects of inhaled nitric oxide in right ventricular myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock.

Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2004 Aug;44(4):793–8 Full text

14. Bhat T, Neuman A, Tantary M, Bhat H, Glass D, Mannino W, Akhtar M, Bhat A, Teli S, Lafferty J.

Inhaled nitric oxide in acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review.

Rev Cardiovasc Med 2015;16(1):1–8.

15. Mahdi M, Joseph NJ, Hernandez DP, Crystal GJ, Baraka A, Salem MR.

Induced hypocapnia is effective in treating pulmonary hypertension following mitral valve replacement.

Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2011 Jun;21(2):259-67

16. Evans S, Brown B, Mathieson M, Tay S.

Survival after an amniotic fluid embolism following the use of sodium bicarbonate.

BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014

17. Fuller BM, Mohr NM, Skrupky L, Fowler S, Kollef MH, Carpenter CR.

The Use of Inhaled Prostaglandins in Patients With ARDS: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.

Chest. 2015 Jun;147(6):1510–22 Full text

18. LITFL: Right Ventricular Failure

Further reading

Life In The Fast Lane iNO info

LITFL on Pulmonary Hypertension

Be Like That Guy – Dr John Hinds

The critical care and #FOAMed community lost our friend Dr John Hinds a few days ago.

We’re in the business of sudden death. As prehospital, emergency, acute medicine and intensive care clinicians, facing the reality of the tragic loss of a living person, loved by their friends and family, is our day job. This makes me think we shouldn’t really have any reason to be ‘shocked’ or ‘surprised’. But we have every right to be sad.

The news came in the same week as the tragic Flight for Life Helicopter Crash in Colorado, bringing us another unwelcome reminder of the dangers of prehospital work. My HEMS colleagues and I are always mindful of the possibility that every time we get in the helicopter it could be our last, and I’ve no doubt John appreciated this reality when responding on his motorcycle.

I admired John as he was the quintessential resuscitationist. He was not bound by specialty or location in his passion for excellence in life-saving medicine. He was a master (and innovator) of advanced prehospital emergency medicine in a region where it still barely exists. He was supportive of emergency physicians providing emergency anaesthesia. He performed the first thoracotomy for more than a decade in one hospital, prompting a review of systems, equipment and training and bringing specialties together to embrace multidisciplinary trauma management. He inspired our friends across the world with his approach to intensive care patients.

Two weeks ago John and I gave two of the opening talks at the SMACC conference in Chicago. My talk went first – entitled ‘Advice to a Young Resuscitationist’. I attempted to list a number of tips that could help a resuscitationist become more effective at saving lives while surviving and thriving in our often traumatic milieu. The talk will be uploaded soon, and I’ve listed the pieces of advice below. What strikes me now like a slap across the face with a large wet fish is the realisation that John exemplified every one of these characteristics and habits:

1. Carve your own path that takes you on a richer path than that worn by trainees in a single specialty

John was an anaesthetist, an intensivist, and prehospital doctor.

2. Never waste an opportunity to learn from other clinicians – leave your ego at the door. See any feedback as an opportunity to learn and to improve, no matter how painful it is to receive.

Despite being among the best in his field, John would on occasion discuss challenging cases and ask if we could think of anything else that should have been done (our answer being, without exception, “no”).

3. Have the confidence and self-belief to perform actions you are competent to perform when needed, to avoid the tragedy of acts of omission.

John’s amazing talk on “crack the chest – get crucified” (when no-one else would) shows how he embraced this mindset: do what needs to be done – with honourable intentions – and manage the consequences later.

4. You can’t save every one, but you can make each case count. When a case goes wrong you need to change something – yourself, your colleagues or the system.

John was a super-agent of change wherever he operated. One beautiful example is how in one hospital the thoracotomy tray ended up being named after him!

5. Caring is so critical to what we do, and is one of the most important things to patients and their families.

As Greg Henry taught me (quoting Theodore Roosevelt) : ‘Nobody cares how much you know until they know how much you care’

John was gentle, kind, and humble. So many of his tributes remark on his compassion and dedication to patients.

6. Choose your colleagues & your environment well. Greater team cohesiveness is protective against burnout and compassion fatigue.

John was proud of the teamwork he enjoyed with his ICU colleagues, and worked with forward thinking colleagues who contribute significantly to #FOAMed.

7. Strive for balance in your life and your work. Consider part time working or mixing your critical care with a non-clinical or non-critical care interest.

John was revered and loved within the world of motorcycle racing, a passion he managed to combine with his flair for critical care.

8. Train your brain to be aware of and to utilise strategies that protect it against cognitive traps and avoidable performance limitations under stress – learn the hacks for your MINDWARE.

Many of us now introduce stressors into our simulation training to help us learn to deal with the adrenal load of a difficult resuscitation. But I doubt many of us can hope to achieve the intense focus and concentration under pressure that is required of motorcycle racers. John sent me a link to this video of racer Michael Dunlop a few weeks ago with the comment ‘How about this for a scare!’

9. Maintain perspective. It’s not all about you or your resus room.The most effective resuscitationists save lives when they’re not there. They work on the systems – the processes, the training, the governance, the audit, the research.

John was a brilliant educator and systems thinker. The care given at the roadside, in the ED, the ICU and the operating room at many sites is better because of the teaching he gave and the approaches he developed.

10. Understand that everything you say and do in a resuscitation casts memorable impressions in trainees’ minds like the tossing of pebbles into a pond, whose ripples reach out and out to affect so many future lives and deaths in other resuscitation rooms.

You can imagine the obstacles and personalities John faced when trying to improve care in the environments in which he worked. But through it all he remained a gentleman. Always constructive, always collaborative, always supportive. I’ve never heard him say a bad word about any named individual or criticise another specialty. He truly embodied the non-tribal spirit of SMACC, which sets an example for us all to aspire to, and will influence future resuscitation room behaviour in far-reaching locations.

11. Behave as you would want to be remembered, and be mindful of the extent of the ripples in the pond. But don’t let that put you off throwing the pebbles – embrace the challenge of the highs and lows and above all enjoy the ride, for it is awesome.

In just 35 years of life John saved the lives of many and changed the lives of many more. He knew how to throw pebbles and wasn’t afraid to point out the lack of emperor’s clothes around many traditional aspects of medical practice. And that smile seen in all the pictures of him shows there’s no doubt John enjoyed the ride, and it was awesome. Thanks to his wit, intelligence, teaching, charm, and resuscitation brilliance, he helped us enjoy it all the more too.

I spent a lot of time preparing my talk ‘Advice to a Young Resuscitationist’. It’s clear to me now that I needn’t have bothered. Sharing the stage with John, I could have saved everyone’s time by simply saying: ‘Try to be like THIS guy’.

I am extremely privileged to know him, to have learned from him, and to have shared some moments from his days at smaccUS.

We will mourn, we will remember, and we will honour him by being the best resuscitationists we can.

You can also honour him by signing the Northern Ireland Air Ambulance petition

Pre-SMACC mini RAGE

Currently the RAGE Podcast site is recovering from a cold, so here are the show notes for the pre-SMACC mini RAGE episode released June 2015.

Here is the podcast

And here are the references:

SMACC Conference

It’s a knockout

GoodSAM

GoodSAM App

Oxygen therapy

AVOID: Air Versus Oxygen in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction.

HOT or NOT trial: HyperOxic Therapy OR NormOxic Therapy after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (HOT OR NOT): a randomised controlled feasibility trial.

Helicopter Emergency Medical Services

Survival benefit of a physician-staffed HEMS assistance for severely injured patients

Willingness to pay for lives saved by HEMS

Intraosseous access

Intraosseous infusion rates under high pressure: a cadaveric comparison of anatomic sites.

Intraosseous hypertonic saline: myonecrosis in swine

Intraosseous hypertonic saline: safe in swine

Discussion post about intraosseous hypertonic saline at Sydney HEMS

Handstands

Handstands: a treatment for supraventricular tachycardia?

Impact of a modified Valsalva manoeuvre in the termination of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia

Handstands keep you awake

The next RAGE Podcast will air late August / early September

Post-arrest hypothermia in children did not improve outcome

Many clinicians extrapolate adult research findings to paediatric patients because there’s no alternative, and until now we’ve had to do that with post-cardiac arrest therapeutic hypothermia after paediatric cardiac arrest.

However the THAPCA trial in the New England Journal of Medicine now provides child-specific data.

It was a multicentre trial in the US which included children between 2 days and 18 years of age, who had had an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and remained comatose after return of circulation. They were randomised to therapeutic hypothermia (target temperature, 33.0°C) or therapeutic normothermia (target temperature, 36.8°C) within 6 hours after the return of circulation.

Therapeutic hypothermia, as compared with therapeutic normothermia, did not confer a significant benefit with respect to survival with good functional outcome at 1 year, and survival at 12 months did not differ significantly between the treatment groups.

These findings are similar to the adult TTM trial, although there are some interesting differences. In the paediatric study, the duration of temperature control was longer (120 hrs vs 36 hrs in the adult study), respiratory conditions were the predominant cause of paediatric cardiac arrest (72%), and there were only 8% shockable rhythms in the paediatric patients, compared with 80% in the adult study.

The full text is available here.

Therapeutic Hypothermia after Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest in Children

N Engl J Med. 2015 Apr 25

[EXPAND Abstract]

Background: Therapeutic hypothermia is recommended for comatose adults after witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, but data about this intervention in children are limited.

Methods: We conducted this trial of two targeted temperature interventions at 38 children’s hospitals involving children who remained unconscious after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Within 6 hours after the return of circulation, comatose patients who were older than 2 days and younger than 18 years of age were randomly assigned to therapeutic hypothermia (target temperature, 33.0°C) or therapeutic normothermia (target temperature, 36.8°C). The primary efficacy outcome, survival at 12 months after cardiac arrest with a Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, second edition (VABS-II), score of 70 or higher (on a scale from 20 to 160, with higher scores indicating better function), was evaluated among patients with a VABS-II score of at least 70 before cardiac arrest.

Results: A total of 295 patients underwent randomization. Among the 260 patients with data that could be evaluated and who had a VABS-II score of at least 70 before cardiac arrest, there was no significant difference in the primary outcome between the hypothermia group and the normothermia group (20% vs. 12%; relative likelihood, 1.54; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.86 to 2.76; P=0.14). Among all the patients with data that could be evaluated, the change in the VABS-II score from baseline to 12 months was not significantly different (P=0.13) and 1-year survival was similar (38% in the hypothermia group vs. 29% in the normothermia group; relative likelihood, 1.29; 95% CI, 0.93 to 1.79; P=0.13). The groups had similar incidences of infection and serious arrhythmias, as well as similar use of blood products and 28-day mortality.

Conclusions: In comatose children who survived out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, therapeutic hypothermia, as compared with therapeutic normothermia, did not confer a significant benefit in survival with a good functional outcome at 1 year.

[/EXPAND]