Where I work high flow humidified nasal cannula oxygen (HFNC) is used for infants with bronchiolitis and our ICU also employs it for selected adult patients. This is a relatively recent addition to our choice of oxygen delivery systems, and many emergency physicians may still be unfamiliar with it.

A recent review outlines the (scant) evidence for its use in neonates, infants, and adults, and proposes some mechanisms for its effect.

It’s a bit like the traditional delivery of oxygen via nasal cannulae. However, it is recommended that flow rates above 6 l/min are heated and humidified, so the review referred to heated, humidified, high flow nasal cannulae (HFNC).

Neonates

HFNC began as an alternative to nasal CPAP for premature infants. There are as yet no definitive studies showing its superiority over CPAP.

Infants

HFNC may decrease the need for intubation when compared to standard nasal cannula in infants with bronchiolitis.

Adults

No hard outcome data yet exist. It has mainly been used for hypoxemic respiratory failure rather than patients with hypercarbia such as COPD patients.

How it works

The following are proposed mechanisms for improvements in gas exchange / oxygenation:

1. A high FiO2 is maintained because flow rates are higher than spontaneous inspiratory demand, compared with standard facemasks and low flow nasal cannulae which entrain a significant amount of room air.

2. Nasopharyngeal dead space ‘washout’. The additional gas flow within the nasopharyngeal space may reduce dead space: tidal volume ratio. There are some animal neonatal data to show improved CO2 clearance with flows up to 8 l/min.

3. Stenting of the upper airway by positive pressure may decrease upper airways resistance and reduce work of breathing.

4. Some positive pressure (akin to CPAP) may be generated, which can help recruit lung and decrease ventilation–perfusion mismatch; however this is not consistently present in all studies, and high flows are needed to generate even modest pressures. For example, in a study on postoperative cardiac surgery patients, HFNC at 35 l/min generated a nasopharyngeal pressure of only 2.7 ± 1 cmH2O.

Drawbacks and things to know

Studies suggest that if benefit is going to be seen in adult or paediatric patients, this should be evident in the first 30-60 minutes.

Any modest positive pressure generated will be reduced by an open mouth or when there is a significant leak between the cannulae and the nares.

HFNC maintain a fixed flow and generate variable pressures, and the pressures may be more inconsistent in patients with respiratory distress with high respiratory rates and mouth breathing. Compare this with non-invasive ventilation (CPAP and or BiPAP) in which variable flow is used to generate a fixed pressure.

The authors’ summary is helpful:

We postulate that the predominant benefit of HFNC is the ability to match the inspiratory demands of the distressed patient while washing out the nasopharyngeal dead space. Generation of positive airway pressure is dependent on the absence of significant leak around the nares and mouth and seems less likely to be a predominant factor in relieving respiratory distress for most patients.

NIV such as CPAP and bilevel positive airway pressure should still be considered first line therapy in moderately distressed patients in whom supplementation oxygen is insufficient and when a consistent positive pressure is indicated.

There are numerous ongoing trials which should hopefully clarify indications for HFNC and the mechanisms by which it may be beneficial.

An earlier summary of the evidence was written by my Scandinavian chums. And Reuben Strayer uses it to optimise oxygenation during RSI as a modification of the NODESAT technique.

Use of high flow nasal cannula in critically ill infants, children, and adults: a critical review of the literature

Intensive Care Med. 2013 Feb;39(2):247-57

[EXPAND Abstract]

BACKGROUND: High flow nasal cannula (HFNC) systems utilize higher gas flow rates than standard nasal cannulae. The use of HFNC as a respiratory support modality is increasing in the infant, pediatric, and adult populations as an alternative to non-invasive positive pressure ventilation.

OBJECTIVES: This critical review aims to: (1) appraise available evidence with regard to the utility of HFNC in neonatal, pediatric, and adult patients; (2) review the physiology of HFNC; (3) describe available HFNC systems (online supplement); and (4) review ongoing and planned trials studying the utility of HFNC in various clinical settings.

RESULTS: Clinical neonatal studies are limited to premature infants. Only a few pediatric studies have examined the use of HFNC, with most focusing on this modality for viral bronchiolitis. In critically ill adults, most studies have focused on acute respiratory parameters and short-term physiologic outcomes with limited investigations focusing on clinical outcomes such as duration of therapy and need for escalation of ventilatory support. Current evidence demonstrates that HFNC generates positive airway pressure in most circumstances; however, the predominant mechanism of action in relieving respiratory distress is not well established.

CONCLUSION: Current evidence suggests that HFNC is well tolerated and may be feasible in a subset of patients who require ventilatory support with non-invasive ventilation. However, HFNC has not been demonstrated to be equivalent or superior to non-invasive positive pressure ventilation, and further studies are needed to identify clinical indications for HFNC in patients with moderate to severe respiratory distress.

[/EXPAND]

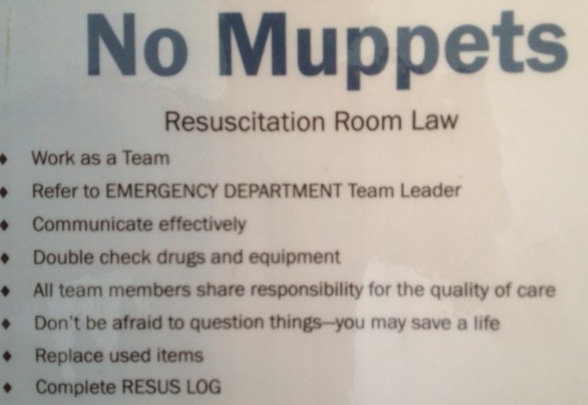

The first is ‘muppet’. This does not refer to the much loved and trademarked invention of Jim Henson, (and now property of Disney) – a word originally thought to be a synthesis of ‘marionette’ and ‘puppet’. If I were referring to these wonderful icons of children’s televisual theatre I would capitalise the ’m’. Nope. I refer to the British meaning, which the

The first is ‘muppet’. This does not refer to the much loved and trademarked invention of Jim Henson, (and now property of Disney) – a word originally thought to be a synthesis of ‘marionette’ and ‘puppet’. If I were referring to these wonderful icons of children’s televisual theatre I would capitalise the ’m’. Nope. I refer to the British meaning, which the

When the external muppet factor is allowed to escalate unchecked, the end result is frenetic activity and noise from the staff without coordinated meaningful intervention for the patient. Comparisons with ‘headless chickens’ are often drawn. In particularly challenging scenarios, it can appear that the panic has swelled to such magnitude that it goes nova, as though the headless chickens have actually exploded, metaphorically filling the room with a gruesome blanket of giblets and a snowstorm of feathers, clouding ones ability to assess and manage the patient effectively. This high-point of group anxiety and ineffectiveness is what I mean by the term ’chicken bomb’, and I bet most readers of this blog will have witnessed the detonation of one.

When the external muppet factor is allowed to escalate unchecked, the end result is frenetic activity and noise from the staff without coordinated meaningful intervention for the patient. Comparisons with ‘headless chickens’ are often drawn. In particularly challenging scenarios, it can appear that the panic has swelled to such magnitude that it goes nova, as though the headless chickens have actually exploded, metaphorically filling the room with a gruesome blanket of giblets and a snowstorm of feathers, clouding ones ability to assess and manage the patient effectively. This high-point of group anxiety and ineffectiveness is what I mean by the term ’chicken bomb’, and I bet most readers of this blog will have witnessed the detonation of one.